- Preparation of Tin Oxide Nanoparticles and Carbon Nanotube Fiber Nanocomposites for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes

Yumin Lee*, Seungho Ha*, Nayoung Ku*, Kyunbae Lee*, Yeonsu Jung*, Taehoon Kim*†

*Composites & Convergence Materials Research Division, Korea Institute of Materials Science, Korea

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Carbon nanotube fibers (CNTFs) are a macroscale material with high conductivity and porosity, and they hold promise as an electrode material for lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), without the need for conducting agents, binders, or current collectors. In this study, to develop an eco-friendly and scalable approach for manufacturing LIB anodes, we investigated the morphological characteristics and anode performance of SnO2@CNTF nanocomposites synthesized under various conditions. Synthesis experiments were conducted with different temperatures, different precursor concentrations, and different synthesis times. Under high temperatures and high precursor concentrations, SnO2 nanoparticles grew uniformly and formed a porous structure through which the electrolyte could penetrate deep into the fiber. Furthermore, the effect of the heat treatment temperature of the SnO2@CNTF was examined, and it was found that higher temperatures led to coarsening and reduction, resulting in performance degradation. Increasing the synthesis time increased the proportion of tin oxide, which in turn increased the overall capacity at low charge-discharge rates. However, for synthesis times exceeding 24 h, the specific capacity at high charge-discharge rates decreased significantly. The results of this study provide insights into the synthesis conditions of tin oxide and the effect of the conditions on the morphology, structure, and anode performance of the compound.

Keywords: CNT Fiber, Tin Oxide, Lithium-ion Battery, Anode, CNT Yarn

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have the potential to be widely used in diverse fields, owing to their exceptional properties such as high electrical conductivity, high specific surface area, and remarkable strength [1]. However, for the fabrication of macroscale materials such as films or fibers, it is often necessary to use a binder or dispersant, which results in the macroscale material having physical properties considerably different from those of CNTs. CNT fibers (CNTFs) produced via direct spinning are synthesized continuously from carbon sources and catalysts, and a binder or dispersant is not required. Direct-spun CNTFs are used in many applications, owing to their high pore density, low mass density, remarkable flexibility, superior strength, and high electrical conductivity [2-4]. In particular, functional nanomaterials can be incorporated into the nanopores of CNTFs. Such incorporation of functional nanomaterials modifies the physical properties of CNTFs and renders them suitable for many applications.

Considering the advantageous properties of nanocomposites composed of active materials and CNTFs, numerous studies have attempted to develop energy storage systems based on such nanocomposites. Several research groups have reported the preparation of fibrous supercapacitors by growing polyaniline [5], porous carbon [6], metal oxide [7,8] and MXene [9] on direct-spun CNTFs. Furthermore, CNTF-based lithium-ion batteries have gained attention because of their higher energy density compared with supercapacitors [10-12]. Our recent study [13] developed a CNTF anode comprising surface-treated CNTFs and tin oxide for lithium-ion batteries. We used a modified sensitization method for electroless plating to synthesize the tin oxide at a low temperature (<100°C) in an aqueous system, without employing any hydrothermal method [14]. This approach can be used to prepare anode materials in an environmentally friendly and scalable manner [15-17]. The performance of alloying and conversion anode materials, such as tin oxide, is significantly influenced by their nanostructure, size, and morphology. However, the relationship between nanocomposite synthesis conditions of the modified sensitization method and nanocomposite characteristics has not been investigated.

In this work, we investigated the optimum structures of nanocomposites comprising tin oxide and CNTFs for identifying the optimum structure best suited for use as an anode in a lithium-ion battery. We prepared a series of SnO2@CNTF nanocomposites using the facile stirring method by varying the synthesis time, temperature, precursor concentration, and thermal annealing conditions, and the morphology and anode performance of the SnO2@CNTF nanocomposites were determined. By using an optimized synthesis time and a highly concentrated precursor solution, we obtained small tin oxide nanoparticles in the nanocomposite, which resulted in the nanocomposite exhibiting high anode performance [18]. In particular, the addition of a conducting agent, binder, or current collector to the anode materials, which increases the weight of lithium-ion batteries, was not required.

2.1 Preparation of SnO2@CNTF

CNTFs were prepared using the direct spinning method and conditions employed in a previous study [13,19]. The synthesized CNTFs were immersed in a solution containing 150 mL of deionized water, 1.5 mL of hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%, Sigma-Aldrich), and tin chloride (SnCl2, anhydrous, Alfa Aesar). CNTF samples were synthesized with solutions containing different concentrations of tin chloride. Subsequently, the sample was washed with 1 M HCl and deionized water and subjected to heat treatment for 3 h to obtain SnO2@CNTF. To investigate the effect of synthesis conditions, we varied the synthesis temperature (45°C to 90°C), tin chloride concentration (20 to 80 mg/mL), and synthesis time (4 to 48 h). For the thermal annealing process, samples were prepared under different conditions, including in an air atmosphere at 300°C (the reference sample) and in an argon atmosphere at 600°C and 900°C. For experiments controlling variables other than heat treatment, heat treatment was conducted at 300°C. The tin oxide content in SnO2@CNTF was determined by comparing the weights before and after the nanocomposite’s synthesis.

2.2 Characterization

The morphology and elemental composition of SnO2@ CNTF were determined using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (SU8230, Hitachi) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) system. X-ray diffraction patterns were obtained using a Rigaku D/Max-2500VL X-ray diffractometer (Cu Kα radiation; current: 300 mA; voltage: 40 kV) in the 2θ range of 10° to 70°.

2.3 Electrochemical measurements

The synthesized SnO2@CNTF was tested in a glove box (O2, H2O < 1 ppm). A 3 cm SnO2@CNTF sample was directly used as the anode in a coin cell (2032 type) with 1 M LiPF6 in ethylene carbonate/diethylene carbonate (EC:DEC, 1:1 v/v) as the electrolyte and a Celgard 2400 separator. The coin cell also included Li metal. Charge-discharge tests were conducted in the voltage range of 0.01-3.0 V (vs. Li/Li+) by using an electrochemical station (Automatic Battery Cycler, WBCS3000L, WonATech, Seoul, Korea).

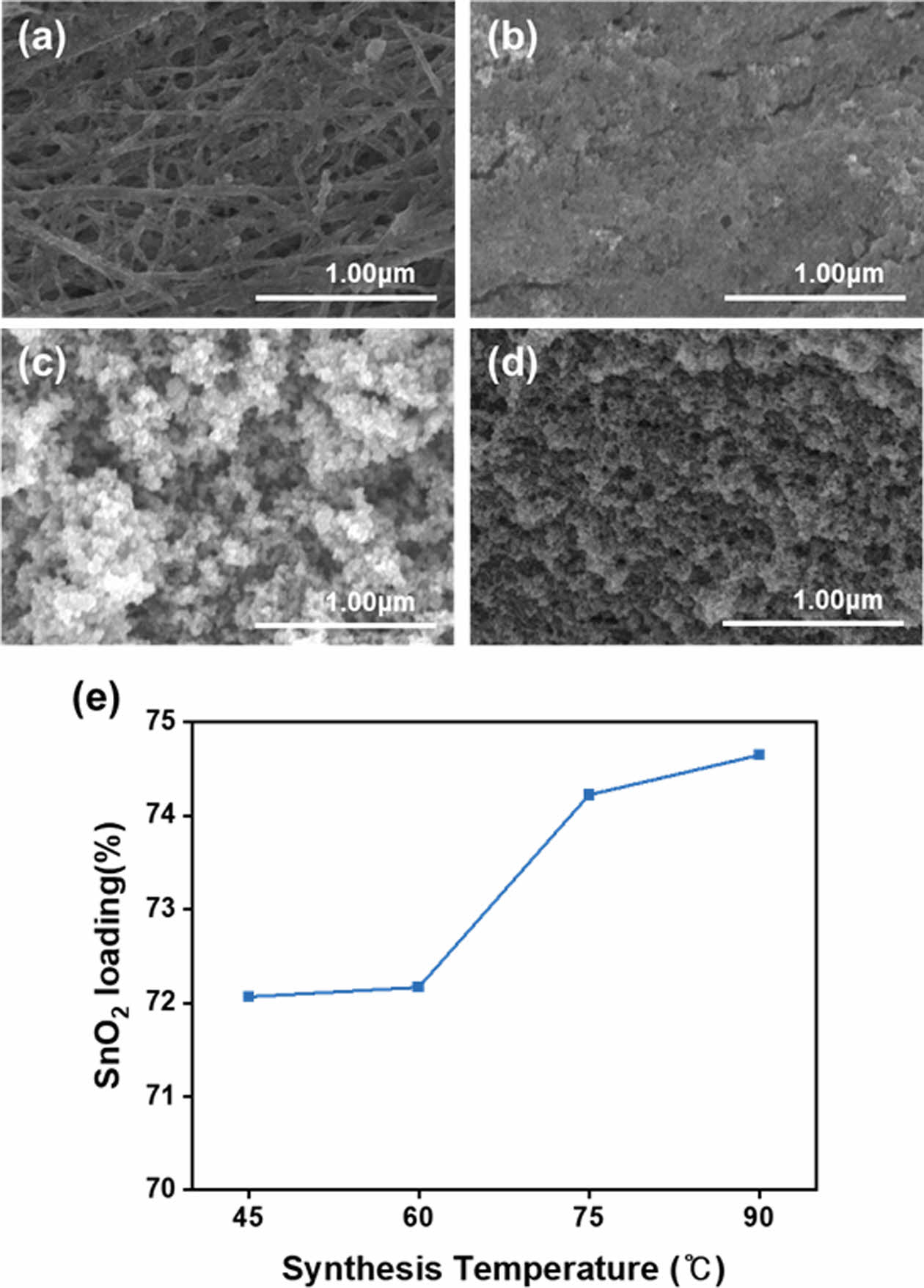

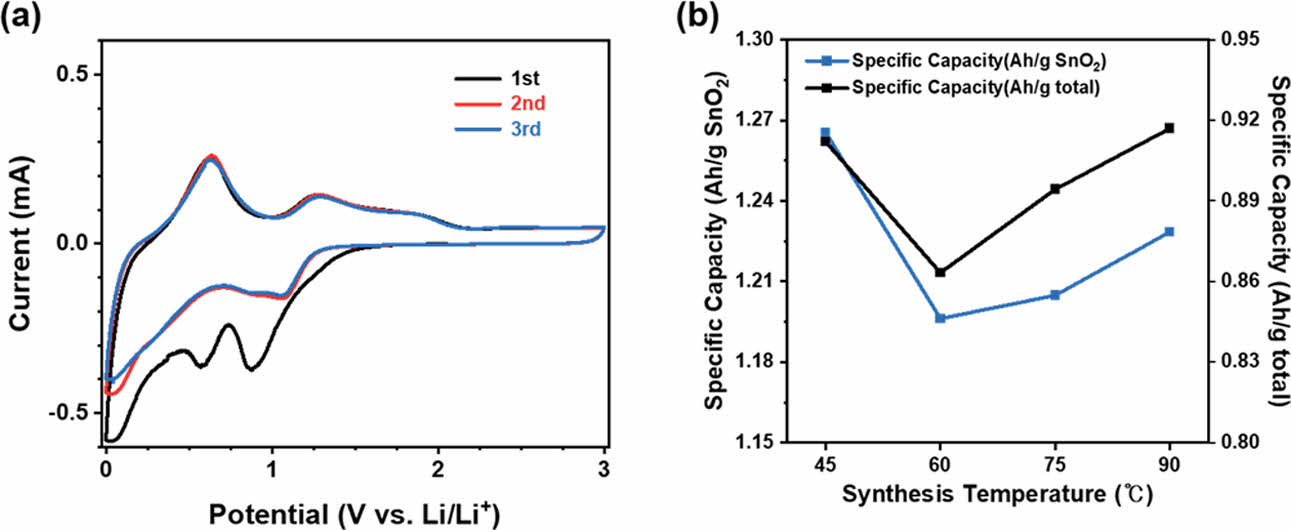

To investigate the characteristics of SnO2@CNTF nanocomposites and their effects on the anode performance, we synthesized tin oxide nanoparticles at various temperatures and with various precursor solution concentrations. Fig. 1(a–d) shows the morphologies of SnO2@CNTF nanocomposites synthesized at different temperatures. As the synthesis temperature increased, the tin oxide content of the nanocomposite slightly increased (from 72.1 wt% to 74.6 wt%, see Fig. 1(e)), and the surface morphology of the fibers changed significantly. Regardless of the synthesis temperature, when the precursor solution concentration remains the same, the amount of tin oxide precursor present in the solution is fixed, leading to a similar growth quantity. On the other hand, the growth behavior varies significantly depending on the temperature. At higher temperatures, the rapidly grown tin oxide on the surface prevents further penetration of the solution into the fiber interior, whereas at lower temperatures, the tin oxide grows slowly and evenly, as observed in the images. Both the tin oxide content and the morphology of the nanocomposite could influence the anode performance. Specifically, a higher SnO2 content in the nanocomposite is expected to lead to higher active material content and improved performance. Furthermore, previous studies have indicated that the morphology of SnO2 nanoparticles also plays a crucial role in the anode performance, as larger particles can degrade the performance [20,21]. To verify this, we conducted cell tests using the synthesized SnO2@CNTF nanocomposites, and Fig. 2(a) shows typical cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves observed for the tin oxide anode [13,18]. The cathodic peaks around 0.7 and 0.9 V appearing in the first cycle are attributed to the solid electrolyte interface (SEI) layer formation, a common phenomenon observed in tin-oxide-based [22-24]. The anode capacity was found to depend on the synthesis temperature: nanocomposites synthesized at 45°C exhibited slightly higher anode capacity than the other three nanocomposite samples (Fig. 2(b)). This observation can be attributed to the uniform growth of SnO2 nanoparticles within each CNT bundle of the CNTF and to the presence of residual pores in the fibers. The pores facilitated easier electrolyte penetration into the structure, resulting in relatively better anode performance. However, when calculating the specific capacity relative to the total weight of the CNTF, we obtained slightly different results. For instance, the sample synthesized at 90°C exhibited a specific capacity of 917 mAh/g, slightly higher than the sample synthesized at 45°C, which showed a specific capacity of 912 mAh/g (see Fig. 2(b)). This can be attributed to the higher active material content of the nanocomposite synthesized at 90°C. It is expected that if the active material content could be further increased while ensuring a uniform growth morphology within the bundles, higher performance can be achieved.

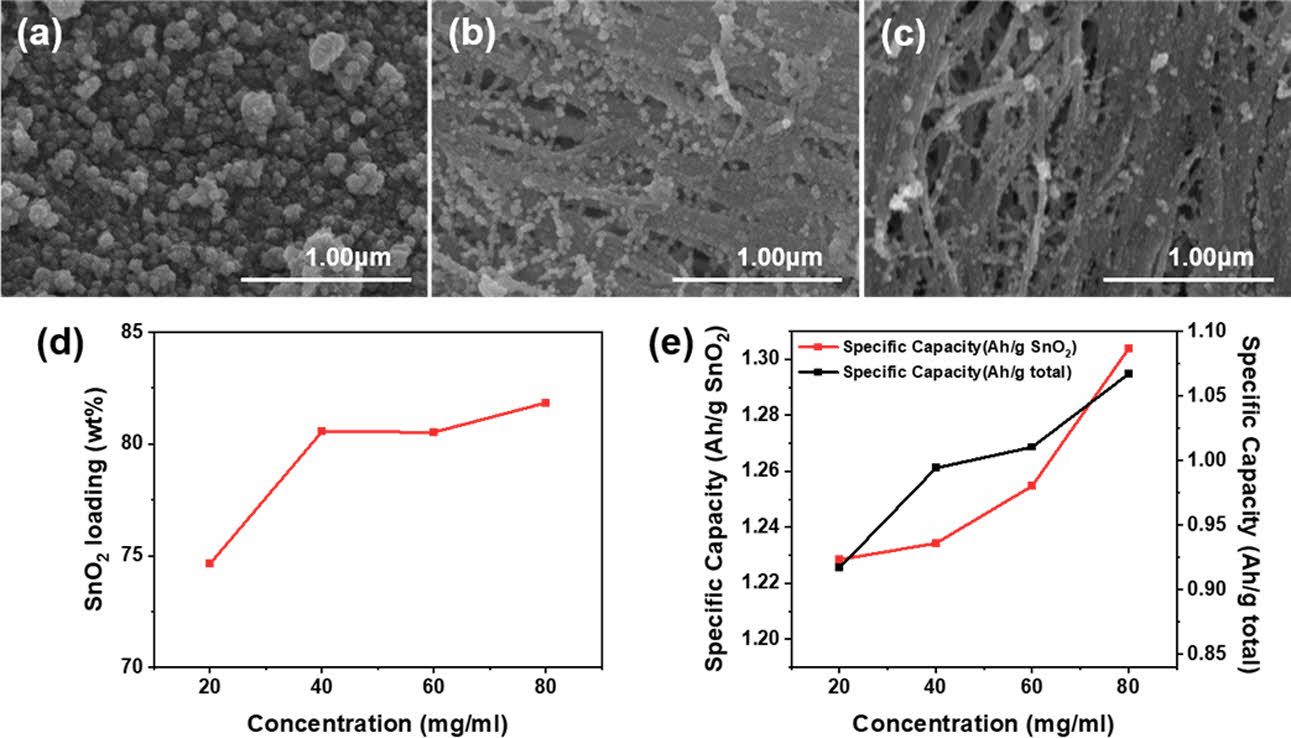

To determine the effects of the precursor solution concentration on the morphology, tin oxide content, and anode performance, the synthesis temperature was fixed at 90°C and the concentration of the precursor solution was varied. With increasing concentration, two distinct characteristics were observed. First, as the concentration increased, a more uniform distribution of tin oxide nanoparticles within the CNTF was observed, without the aggregation of tin oxide nanoparticles (Fig. 3(a–c)). This is likely because, at high concentrations, a large number of nucleation events occur rapidly in the initial stage, leading to uniform growth, whereas at low concentrations, the limited number of nucleation sites results in slower growth. Second, the SnO2 content could be increased up to 80 wt%, which is desirable for an increase in the capacity relative to the total mass of the electrode (Fig. 3(d)). However, at concentrations above 40 mg/ml, the SnO2 content saturated, similar to the trend observed in previous studies where SnO2 was grown on graphene [25]. The anode performance consistently increased with the precursor concentration (see Fig. 3(e)), which can be attributed to the morphological changes observed in Fig. 3(a–c). The morphology with uniformly grown SnO2 within the bundles, which can be seen in Figs. 1(a) and 3(c), was considered the optimal morphology. Consequently, at high precursor concentrations, the synthesized samples showed high anode performance along with a large amount of tin oxide nanoparticles in their interior. Hence, the overall capacity of the nanocomposite electrode was considerably high, reaching a maximum specific capacity of 1,067 mAh/g for a concentration of 80 mg/ml. This capacity is much higher than the commonly used graphite electrode, whose typical capacity is 372 mAh/g. It should be noted that the calculated capacity in this study was based on the total mass of the anode, including the weights of the active material, conductive additive, binder, and current collector. In typical graphite electrodes, when the weights of the conductive additive, binder, and current collector are considered, proportion of the active material by weight is usually less than half.

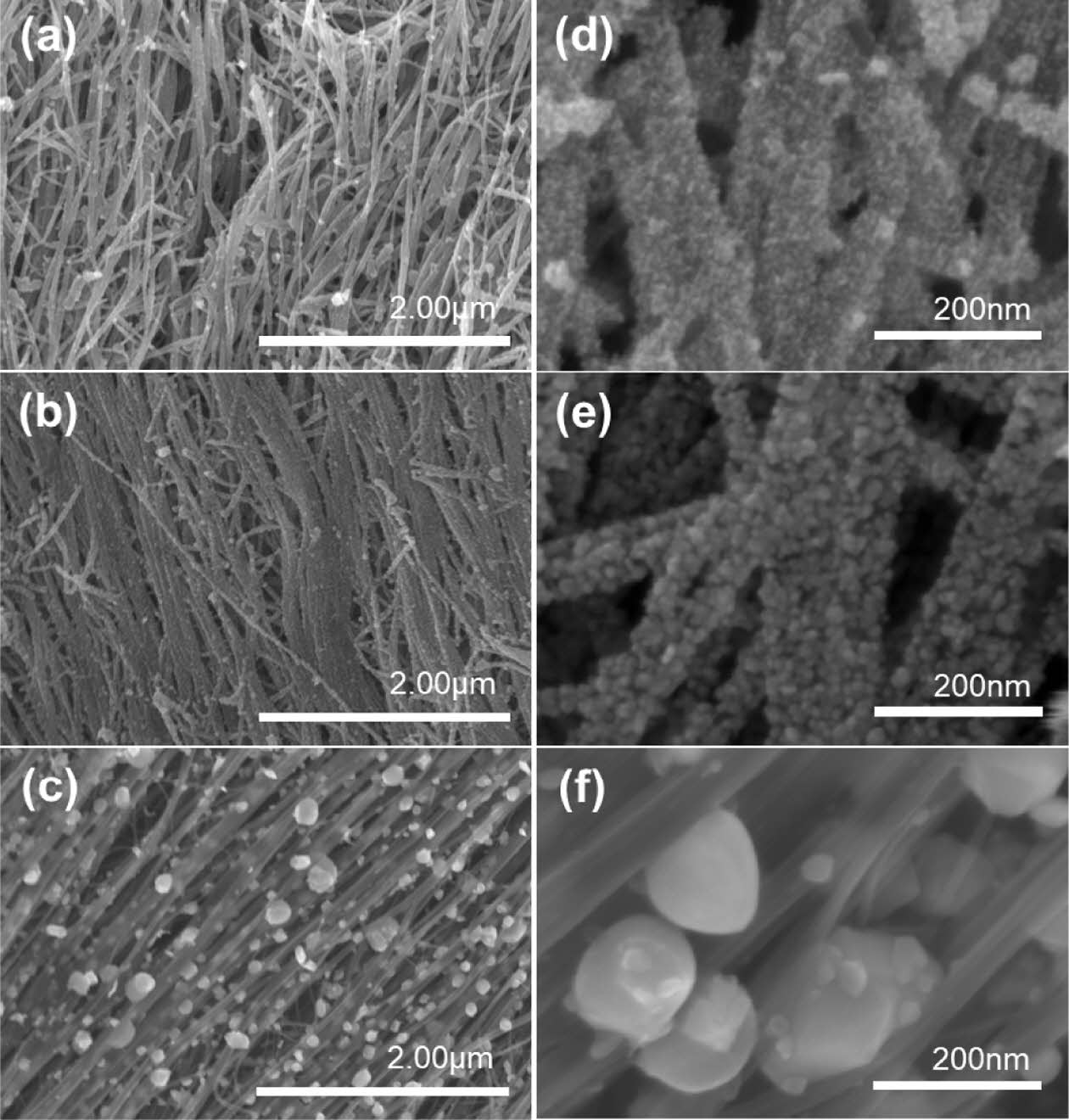

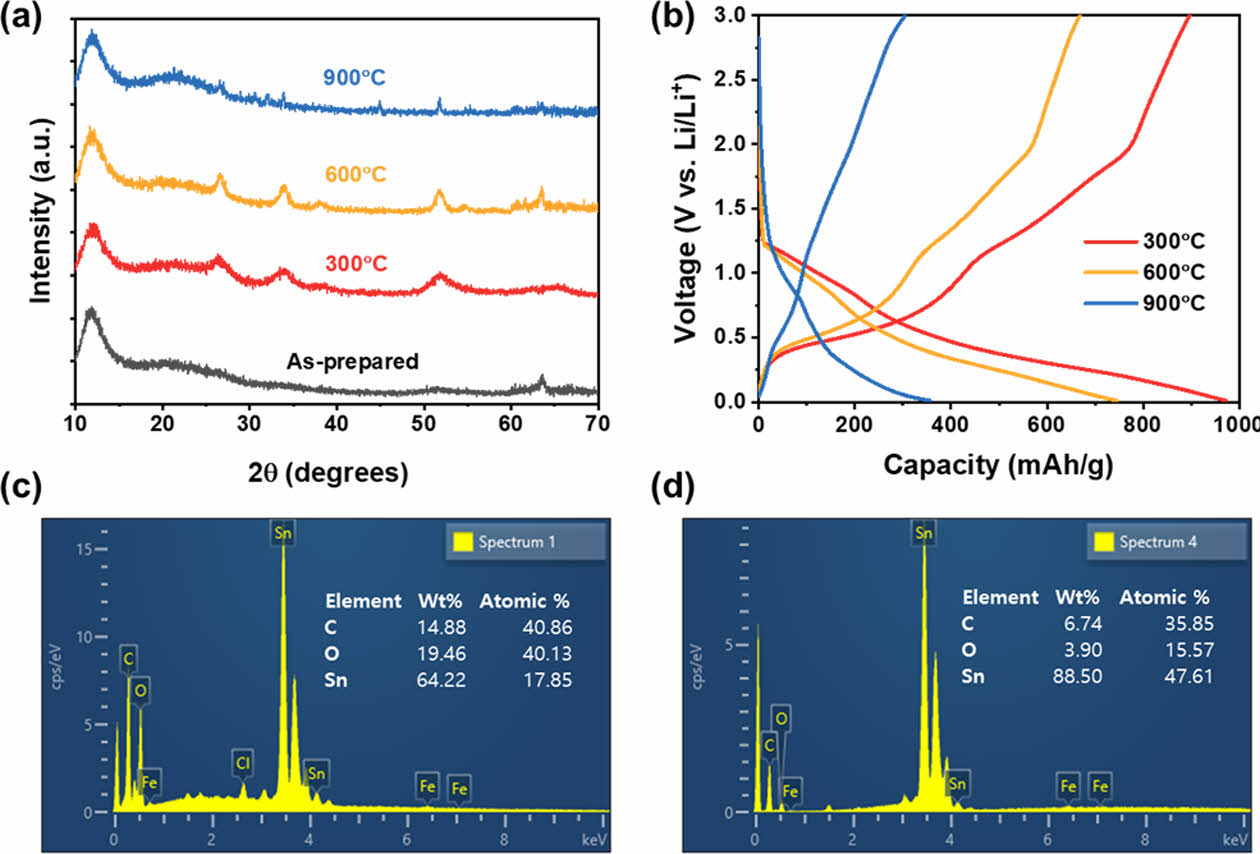

The tested electrodes were thermally annealed under the same conditions as our previous research: 300°C in an air atmosphere [13]. To observe the changes in the characteristics of SnO2@CNTF nanocomposites with the heat treatment conditions, samples of SnO2@CNTF nanocomposites were synthesized under the same synthesis conditions (90°C, 80 mg/ml, 24 hours) and thermally annealed under three conditions. Annealing at 600°C and 900°C was performed in an argon atmosphere since the CNTF could be degraded in an air atmosphere, while annealing at 300°C was conducted in an air atmosphere. Fig. 4 shows SEM images of samples annealed at different temperatures. The samples annealed at 300°C and 600°C exhibited similar morphologies, with the growth of tin oxide nanoparticles on the bundles. However, at higher magnification, slightly larger tin oxide nanoparticles were observed in the samples annealed at 600°C. The sample annealed at 900°C exhibited a different morphology and quite different characteristics. First, the particle size was significantly larger (>100 nm). Second, the particles were located between bundles rather than on the bundles. This is attributed to the reduction of tin oxide nanoparticles to metallic tin at high temperatures, and their coalescence during annealing. The coalesced nanoparticles observed in the SEM image (see Fig. 4(c, f) were tin nanoparticles [26,27].

XRD patterns of the fibers obtained after heat treatment at each temperature are shown in Fig. 5(a). The diffraction peaks observed around 26°, 33°, and 52° correspond to the (110), (101), and (211) planes of tin oxide, respectively, indicating the growth of tin oxide nanoparticles [28]. After heat treatment at 300°C, broad peaks were observed; these peaks were not observed in XRD patterns obtained before the annealing process. After heat treatment at 600°C, the XRD peaks narrowed and their intensity increased, indicating higher crystallinity and a larger particle size, consistent with the observations made from SEM images [29]. In the sample annealed at 900°C, XRD peaks corresponding to tin oxide disappeared, indicating the reduction of tin oxide, and weak peaks of Sn were partially observed. Since the distinction is not very clear, EDS analysis was conducted for a more precise evaluation. Fig. 5(c, d) presents the EDS analysis results of the samples heat-treated at 300°C and 900°C, respectively. In the sample treated at 300°C, the oxygen-to-Sn ratio exceeds 2:1, whereas in the sample treated at 900°C, the oxygen content is less than half that of Sn. This indicates that a reduction process has occurred.

The samples annealed at different temperatures had similar structures with residual CNTF pores, which facilitated electrolyte penetration into the fibers. However, since their elemental compositions and morphologies were different, they would have exhibited different capacities. Fig. 5(b) presents voltage profiles of the three samples annealed at different temperatures during the third cycle. The capacity indicated on the X-axis is based on the total mass of the electrode, including both SnO₂ and CNTF. The sample annealed at 300°C apparently exhibited a higher capacity than those annealed at 600°C and 900°C. The sample annealed at 600°C showed low performance because of its relatively large particle size, which was observed in SEM images and XRD patterns. The sample annealed at 900°C not only had larger particles but also a higher proportion of metallic tin, which resulted in lower capacity. The conversion reaction, which is evident around 1.2 V in the discharge curve of the sample annealed at 300°C, was not observed for the sample annealed at 900°C [30].

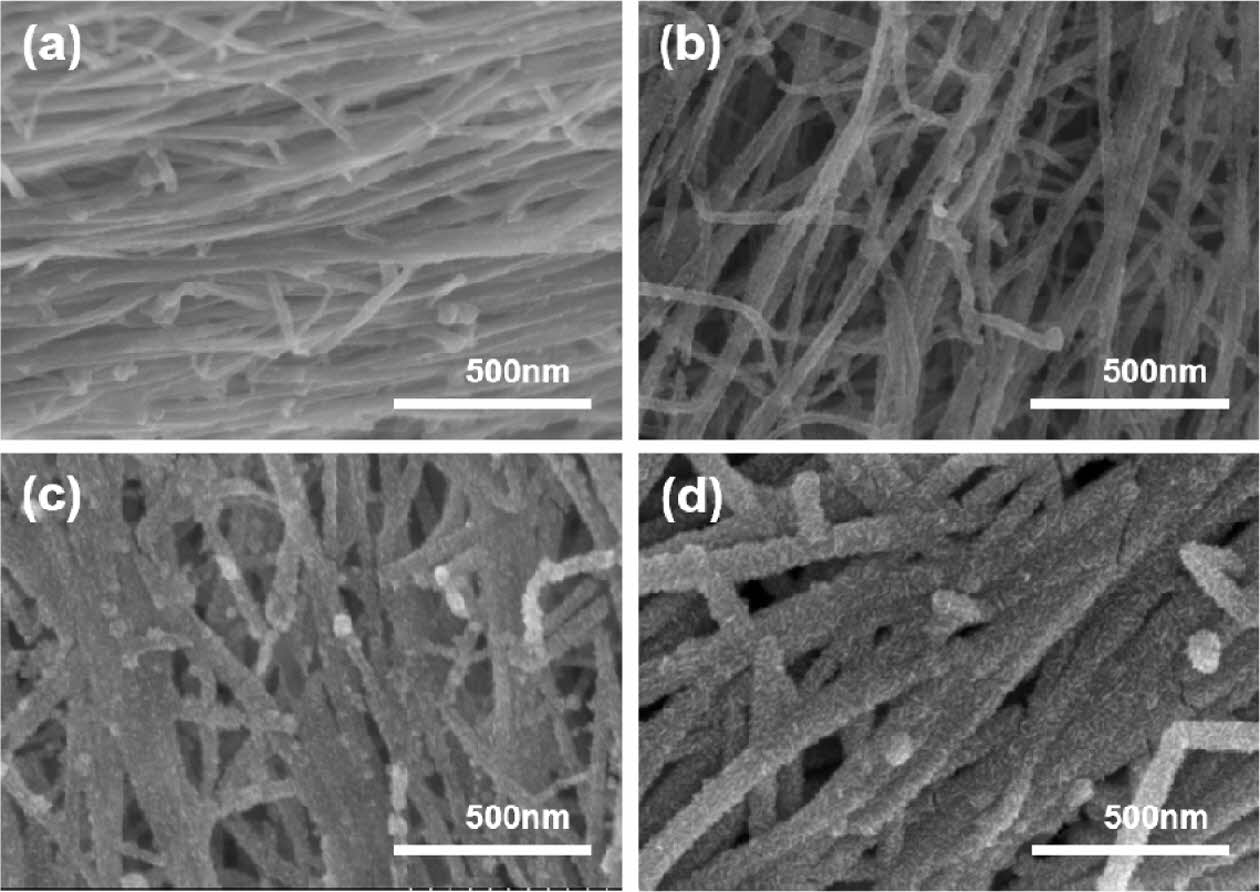

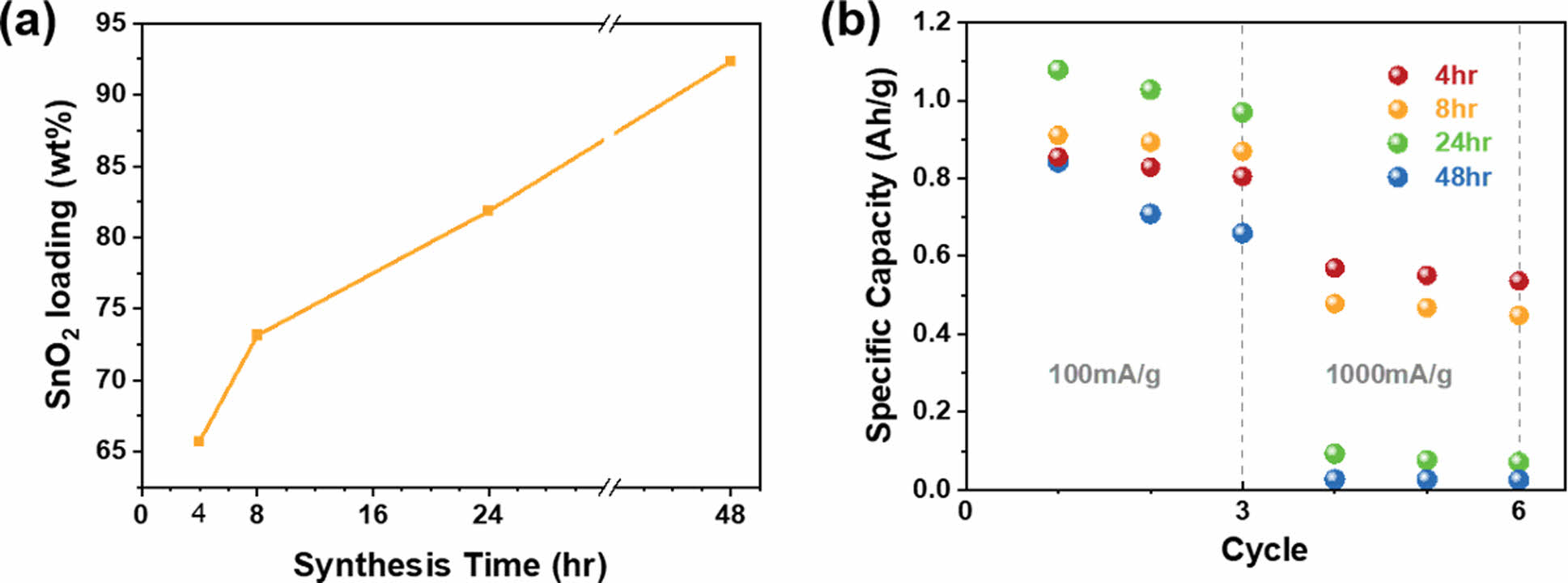

On the basis of the experiments conducted, with the synthesis and annealing conditions fixed at a high temperature (90°C) and a high concentration (80 mg/ml), the effect of the synthesis time on the nanocomposite properties was investigated. By varying the synthesis time from 4 to 48 h, we analyzed the changes in the particle size, loading amount, and capacity under low- and high-rate charge-discharge conditions. Fig. 6 shows the morphology of the fibers in the nanocomposites synthesized over various durations. For all synthesis times, a distinct CNT bundle shape was observed and the high porosity between fibers was well maintained, indicating that an ideal CNT/tin oxide nanocomposite structure could be obtained by maintaining a high temperature and a high precursor concentration during its synthesis. However, as the synthesis time increased, the thickness of the bundles increased and the presence of tin oxide nanoparticles on the surface became more pronounced, indicating an increase in the amount of nanoparticles. This observation is in agreement with intuitive predictions. The loading amount of tin oxide is shown in Fig. 7(a), where even for only 4 h of synthesis, 65.7 wt% of tin oxide nanoparticles grew within the nanocomposite. When the synthesis time was increased to 48 h, the proportion of tin oxide within the nanocomposite reached 92.3 wt%, indicating the growth of a substantial amount of tin oxide nanoparticles (12 g) in the presence of 1 g of CNTF. This suggests that the tin oxide synthesis method proposed in this study is not only simple and environmentally friendly but also highly productive. However, the amount of tin oxide synthesized did not necessarily correlate with the anode capacity. Fig. 7(b) shows the capacity of SnO₂@CNTF relative to the total electrode mass as a function of synthesis time. This observation is interesting as the results of low-rate (100 mA/g) and high-rate (1,000 mA/g) charge-discharge conditions differ slightly. Under low-rate charge-discharge conditions, an increase in the synthesis time led to an increase in the amount of tin oxide within the nanocomposite, which resulted in an increased capacity. However, for the sample with a synthesis time of 48 h, the specific capacity of the anode decreased because of the presence of large tin oxide nanoparticles [31]. Under high-rate charge-discharge conditions, shorter synthesis times were found to be more favorable. The sample synthesized for 4 h exhibited a capacity exceeding 500 mAh/g even at a charge-discharge rate of 1,000 mA/g, which was greater than the capacity of graphite (372 mAh/g). However, when the synthesis time exceeded 24 h, the capacity was below 100 mAh/g. In summary, for systems that require both high capacity and high-speed performance, it is desirable to have a short synthesis time, even if the loading amount of SnO2 nanoparticles is small. On the other hand, for conditions where high-speed charge-discharge is not necessary, a synthesis time of around 24 h would provide the optimal capacity.

|

Fig. 1 Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of SnO2@ CNTF nanocomposites synthesized at (a) 45°C, (b) 60°C, (c) 75°C, and (d) 90°C, and (e) the tin oxide content of the nanocomposites |

|

Fig. 2 (a) CV curves of SnO2@CNTF recorded in the potential range between 0.01 V and 3 V versus Li/Li+ at a scan rate of 0.2 mV/s and (b) the specific capacity of SnO2@CNTF as a function of the synthesis temperature |

|

Fig. 3 SEM images of SnO2@CNTF nanocomposites synthesized at a temperature of 90°C with precursor solution concentrations of (a) 40, (b) 60, and (c) 80 mg/ml. (d) The tin oxide content of the nanocomposites and (e) the specific capacity of the SnO2@CNTF-based anodes |

|

Fig. 4 (a–c) SEM images and (d–f) magnified SEM images of SnO2@CNTF annealed at (a, d) 300°C, (b, e) 600°C, and (c, f) 900°C |

|

Fig. 5 (a) XRD patterns of samples annealed at different temperatures and (b) the third cycle Galvanostatic chargedischarge graph. EDS analysis results of the SnO2@CNTF annealed at (c) 300°C and (d) 900°C |

|

Fig. 6 SEM images of SnO2@CNTF synthesized over different durations: (a) 4, (b) 8, (c) 24, and (d) 48 h |

|

Fig. 7 (a) Proportion of tin oxide in the SnO2@CNTF nanocomposite as a function of the synthesis time and (b) anode capacity for charge-discharge rates of 100 and 1,000 mA/g |

In this study, we synthesized SnO2@CNTF, which exhibits excellent performance as an anode material for secondary batteries, under different conditions by employing the sensitization method used in electroless plating. We evaluated the anode capacity of the synthesized materials. We found that higher synthesis temperatures and higher precursor concentrations facilitated the uniform growth of a larger amount of tin oxide nanoparticles on the surface of the CNT bundle without blocking the pores, resulting in higher capacity. However, when the annealing temperature was too high, the particle size increased, reducing the capacity. In particular, annealing at 900°C resulted in reduced capacity because of the reduction of tin oxide to metallic tin. The particle size was also influenced by the synthesis time: longer synthesis times led to larger particle sizes and higher proportions of tin oxide in the SnO2@CNTF nanocomposite. This resulted in higher capacity under low-rate charge-discharge conditions but a significant decrease in capacity under high-rate charge-discharge conditions. Therefore, for the fabrication of lithium-ion batteries suitable for high-speed charge-discharge, it is desirable to use a short synthesis time. This study demonstrates the importance of the uniform growth of a large amount of tin oxide nanoparticles from the surface to the interior of CNT bundles without blocking the pores of the CNTFs for obtaining an ideal anode material for lithium-ion batteries. In future research, strategies such as the introduction of an additional carbon coating on the synthesized SnO2@CNTF [32] and reduction of the CNTF bundle size for achieving higher SnO2 loading should be examined to develop anode materials with even higher performance. The findings of the present study can also be used for the development of high-performance sodium-ion batteries [33].

This research was supported by the Fundamental Research Program (PNKA610) of the Korea Institute of Materials Science (KIMS). This work was also supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIP) (No. 2022R1C1C1013503).

- 1. Shin, P.-S., Kim, J.-H., DeVries, K.L., and Park, J.-M., “Evaluation of dispersion of MWCNT/cellulose composites sheet using electrical resistance 3D-mapping for strain sensing,” Functional Composites and Structures, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2020, pp. 025004.

-

- 2. Smail, F., Boies, A., and Windle, A., “Direct spinning of CNT fibres: Past, present and future scale up,” Carbon, Vol. 152, 2019, pp. 218-232.

-

- 3. Taylor, L.W., Dewey, O.S., Headrick, R.J., Komatsu, N., Peraca, N.M., Wehmeyer, G., Kono, J., and Pasquali, M., “Improved properties, increased production, and the path to broad adoption of carbon nanotube fibers,” Carbon, Vol. 171, 2021, pp. 689-694.

-

- 4. Weller, L., Smail, F.R., Elliott, J.A., Windle, A.H., Boies, A.M., and Hochgreb, S., “Mapping the parameter space for direct-spun carbon nanotube aerogels,” Carbon, Vol. 146, 2019, pp. 789-812.

-

- 5. Lee, S., Kim, J.-G., Yu, H., Lee, D.-M., Hong, S., Kim, S.M., Choi, S.-J., Kim, N.D., and Jeong, H.S., “Flexible supercapacitor with superior length and volumetric capacitance enabled by a single strand of ultra-thick carbon nanotube fiber,” Chemical Engineering Journal, Vol. 453, 2023, pp. 139974.

-

- 6. Na, Y.W., Cheon, J.Y., Kim, J.H., Jung, Y., Lee, K., Park, J.S., Park, J.Y., Song, K.S., Lee, S.B., and Kim, T., “All-in-one flexible supercapacitor with ultrastable performance under extreme load,” Science Advances, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2022, pp. eabl8631.

-

- 7. Zhang, Q., Sun, J., Pan, Z., Zhang, J., Zhao, J., Wang, X., Zhang, C., Yao, Y., Lu, W., and Li, Q., “Stretchable fiber-shaped asymmetric supercapacitors with ultrahigh energy density,” Nano Energy, Vol. 39, 2017, pp. 219-228.

-

- 8. Choi, C., Kim, S.H., Sim, H.J., Lee, J.A., Choi, A.Y., Kim, Y.T., Lepró, X., Spinks, G.M., Baughman, R.H., and Kim, S.J., “Stretchable, weavable coiled carbon nanotube/MnO2/polymer fiber solid-state supercapacitors,” Scientific Reports, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2015, pp. 9387.

-

- 9. Liu, Q., Yang, J., Luo, X., Miao, Y., Zhang, Y., Xu, W., Yang, L., Liang, Y., Weng, W., and Zhu, M., “Fabrication of a fibrous MnO2@ MXene/CNT electrode for high-performance flexible supercapacitor,” Ceramics International, Vol. 46, No. 8, 2020, pp. 11874-11881.

-

- 10. Liang, J., Li, F., and Cheng, H.-M., “Flexible supercapacitors: Tuning with dimensions,” Energy Storage Materials, Vol. 5, 2016, pp. A1-A3.

-

- 11. Jung, Y., Jeong, Y.C., Kim, J.H., Kim, Y.S., Kim, T., Cho, Y.S., Yang, S.J., and Park, C.R., “One step preparation and excellent performance of CNT yarn based flexible micro lithium ion batteries,” Energy Storage Materials, Vol. 5, 2016, pp. 1-7.

-

- 12. Ren, J., Zhang, Y., Bai, W., Chen, X., Zhang, Z., Fang, X., Weng, W., Wang, Y., and Peng, H., “Elastic and wearable wire‐shaped lithium‐ion battery with high electrochemical performance,” Angewandte Chemie, Vol. 126, No. 30, 2014, pp. 7998-8003.

-

- 13. Ku, N., Cheon, J., Lee, K., Jung, Y., Yoon, S.-Y., and Kim, T., “Hydrophilic and conductive carbon nanotube fibers for high-performance lithium-ion batteries,” Materials, Vol. 14, No. 24, 2021, pp. 7822.

-

- 14. Jeffries, A.M., Wang, Z., Opila, R.L., and Bertoni, M.I., “Tin sensitization and silver activation on indium tin oxide surfaces,” Applied Surface Science, Vol. 588, 2022, pp. 152916.

-

- 15. Sun, L., Si, H., Zhang, Y., Shi, Y., Wang, K., Liu, J., and Zhang, Y., “Sn-SnO2 hybrid nanoclusters embedded in carbon nanotubes with enhanced electrochemical performance for advanced lithium ion batteries,” Journal of Power Sources, Vol. 415, 2019, pp. 126-135.

-

- 16. Li, H., Zhang, B., Zhou, Q., Zhang, J., Yu, W., Ding, Z., Tsiamtsouri, M.A., Zheng, J., and Tong, H., “Dual-carbon confined SnO2 as ultralong-life anode for Li-ion batteries,” Ceramics International, Vol. 45, No. 6, 2019, pp. 7830-7838.

-

- 17. Cho, J.S., and Kang, Y.C., “Nanofibers comprising yolk–shell Sn@ void@ SnO/SnO2 and hollow SnO/SnO2 and SnO2 nanospheres via the Kirkendall diffusion effect and their electrochemical properties,” Small, Vol. 11, No. 36, 2015, pp. 4673-4681.

-

- 18. Zhou, X., Dai, Z., Liu, S., Bao, J., and Guo, Y.G., “Ultra‐uniform SnOx/carbon nanohybrids toward advanced lithium‐ion battery anodes,” Advanced Materials, Vol. 26, No. 23, 2014, pp. 3943-3949.

-

- 19. Kim, T., Shin, J., Lee, K., Jung, Y., Lee, S.B., and Yang, S.J., “A universal surface modification method of carbon nanotube fibers with enhanced tensile strength,” Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, Vol. 140, 2021, pp. 106182.

-

- 20. Kim, C., Noh, M., Choi, M., Cho, J., and Park, B., “Critical size of a nano SnO2 electrode for Li-secondary battery,” Chemistry of Materials, Vol. 17, No. 12, 2005, pp. 3297-3301.

-

- 21. Zhu, J., Zhang, G., Yu, X., Li, Q., Lu, B., and Xu, Z., “Graphene double protection strategy to improve the SnO2 electrode performance anodes for lithium-ion batteries,” Nano Energy, Vol. 3, 2014, pp. 80-87.

-

- 22. Nguyen, T.P., and Kim, I.T., “Self-assembled few-layered MoS2 on SnO2 anode for enhancing lithium-ion storage,” Nanomaterials, Vol. 10, No. 12, 2020, pp. 2558.

-

- 23. Liu, K., Zhu, S., Dong, X., Huang, H., and Qi, M., “Ionic Liquid‐Assisted Anchoring SnO2 Nanoparticles on Carbon Nanotubes as Highly Cyclable Anode of Lithium Ion Batteries,” Advanced Materials Interfaces, Vol. 7, No. 14, 2020, pp. 1901916.

-

- 24. Ding, L., He, S., Miao, S., Jorgensen, M.R., Leubner, S., Yan, C., Hickey, S.G., Eychmüller, A., Xu, J., and Schmidt, O.G., “Ultrasmall SnO2 nanocrystals: hot-bubbling synthesis, encapsulation in carbon layers and applications in high capacity Li-ion storage,” Scientific Reports, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2014, pp. 4647.

-

- 25. Lee, K., Kim, T., Lee, S.B., and Jung, B.M., “Effect of pretreatment on magnetic nanoparticle growth on graphene surface and magnetic performance in electroless plating,” Journal of Nanomaterials, Vol. 2019, No. 1, 2019, pp. 5602742.

-

- 26. Zhang, S., Zhao, H., Ma, W., Dang, L., Yang, S., Zhang, Z., Qiu, D., Feng, Y., and Mi, J., “Rational synthesis of Sn/SnO2/CNFs composite with well-defined structure as anode material for sodium-ion batteries,” Materials Letters, Vol. 336, 2023, pp. 133877.

-

- 27. Xu, Y., Liu, Q., Zhu, Y., Liu, Y., Langrock, A., Zachariah, M.R., and Wang, C., “Uniform nano-Sn/C composite anodes for lithium ion batteries,” Nano Letters, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2013, pp. 470-474.

-

- 28. Liang, S., Yu, K., Li, Y., and Liang, C., “Rice husk-derived carbon@ SnO2@ graphene anode with stable electrochemical performance used in lithium-ion batteries,” Materials Research Express, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2020, pp. 015021.

-

- 29. Bagheri-Mohagheghi, M.-M., Shahtahmasebi, N., Alinejad, M., Youssefi, A., and Shokooh-Saremi, M., “The effect of the post-annealing temperature on the nano-structure and energy band gap of SnO2 semiconducting oxide nano-particles synthesized by polymerizing–complexing sol–gel method,” Physica B: Condensed Matter, Vol. 403, No. 13-16, 2008, pp. 2431-2437.

-

- 30. Sivashanmugam, A., Kumar, T.P., Renganathan, N., Gopukumar, S., Wohlfahrt-Mehrens, M., and Garche, J., “Electrochemical behavior of Sn/SnO2 mixtures for use as anode in lithium rechargeable batteries,” Journal of Power Sources, Vol. 144, No. 1, 2005, pp. 197-203.

-

- 31. Zhang, S., “Chemomechanical modeling of lithiation-induced failure in high-volume-change electrode materials for lithium ion batteries,” npj Computational Materials, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2017, pp. 7.

-

- 32. Yaroslavtsev, A.B., and Stenina, I.A., “Carbon coating of electrode materials for lithium-ion batteries,” Surface Innovations, Vol. 9, No. 2–3, 2020, pp. 92-110.

-

- 33. Kebede, M.A., “Tin oxide–based anodes for both lithium-ion and sodium-ion batteries,” Current Opinion in Electrochemistry, Vol. 21, 2020, pp. 182-187.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 38(2): 67-73

Published on Apr 30, 2025

- 10.7234/composres.2025.38.2.067

- Received on Feb 4, 2025

- Revised on Feb 14, 2025

- Accepted on Mar 3, 2025

Services

Services

- Abstract

1. introduction

2. method

3. results and discussion

4. conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Taehoon Kim

-

Composites & Convergence Materials Research Division, Korea Institute of Materials Science, Korea

- E-mail: tkim67@kims.re.kr

Copyright ⓒ The Korean Society for Composite Materials. All rights reserved.

Copyright ⓒ The Korean Society for Composite Materials. All rights reserved.