- Effect of Lightweight Waste Plastic (LWP) on the Morphology and Properties of EVA Composite Foams

Donghun Han*† , Youngmin Kim*, Danbi Lee*, Jonghwan Lee*, Geonhee Seo*

* Korea Institute of Materials Convergence Technology, Busan 47154, Republic of Korea

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This study evaluated the effects of lightweight waste plastic (LWP) content on the foaming characteristics, crosslinking properties, and mechanical performance of EVA (ethylene-vinyl acetate) composite foams. The analysis of foaming characteristics revealed that as LWP content increased, the foaming ratio decreased and the specific gravity increased, indicating limitations in the lightweight properties of the foams. Crosslinking property measurements showed that an increase in LWP content led to higher crosslink density, which contributed to improvements in mechanical properties such as tensile strength. However, elongation at break and tear strength decreased due to phase separation, reflecting the complex interactions within the material. Mechanical property analysis indicated that hardness and rebound resilience increased with higher LWP content, while recovery performance after compression decreased. The increase in compression set was attributed to reduced network flexibility caused by increased crosslink density and limitations in recovery performance due to phase separation. Furthermore, microscopic analysis demonstrated that higher LWP content resulted in smaller cell sizes, denser cell structures, and increased non-uniformity. These structural changes directly influenced the material properties of the foams, suggesting that phase separation was a major factor in the deterioration of cell structure and mechanical performance. This study highlights the recyclability of EVA/LWP composite foams and confirms the potential of using waste plastics for developing sustainable foam materials. As the LWP blend ratio increases, hardness, resilience, and tensile strength increase, but tear strength, elongation and compression set decrease. The LWP blend ratio of 20-30 wt% is considered optimal, as mechanical strength improves while the reduction in compression set is not significant.

Keywords: EVA, Foaming behavior, EVA recycling, Lightweight waste plastic

EVA (ethylene-vinyl acetate) is a copolymer of ethylene and vinyl acetate (VA) that offers several advantages, including low density, excellent thermal insulation, superior soundproofing, high strength, and corrosion resistance. These properties make it widely used in various applications such as wires, packaging films, adhesives, coatings, foams, injection molding, and extrusion. EVA is typically a polymer with a vinyl acetate content of 5–45% and is derived from polyethylene (PE) [1]. Compared to PE, EVA has relatively lower processing temperatures and density while providing enhanced flexibility, excellent thermal insulation, and corrosion resistance [2]. Additionally, the physical properties of EVA can be easily tailored by adjusting the VA content, allowing for versatile applications [3,4].

EVA's excellent processability enables it to be fabricated into various forms such as films, vinyl sheets, adhesives, and foams. It can also be reinforced through crosslinking to produce stronger materials [5,6]. However, crosslinked EVA transforms into a thermoset, making it non-reprocessable and necessitating disposal through landfill or incineration [7,8]. Such disposal methods result in severe environmental issues, including greenhouse gas emissions and microplastic generation. While research on substituting EVA with biomass-based or biodegradable polymers is ongoing to address these challenges, their practical use remains limited due to processing difficulties and high costs [9,10]. However, the use of lightweight waste plastic (LWP) as the primary polymer component and a functional filler in EVA-based foam systems has not been extensively studied.

In this study, EVA resin was blended with LWP, a form of EVA waste, to produce foams, and their properties were analyzed. The mechanical properties and microcellular structure changes of EVA/LWP composite foams were evaluated with varying LWP content. This research assessed the recyclability of EVA waste and analyzed the characteristics of EVA foams containing lightweight waste plastic at different content levels to determine their commercial viability.

2.1 Experimental Materials and Specimen Fabrication

EVA used in this study was EVA 1315 from Hanwha Chemical, with a vinyl acetate (VA) content of 15%. Lightweight waste plastic (LWP) scrap was provided by Buyoung Co., Ltd. VA content of LWP based on EVA foam is 16-18% and density is 0.9 g/cc.

For the crosslinking agent, Perkadox BC-FF (Dicumyl Peroxide, DCP, 99%) from AkzoNobel was used, which plays a critical role in inducing the crosslinking reaction in EVA and determining the structure and properties of the foam. The blowing agent used was Azodicarbonamide-based JTR/D from Kumyang Co., Ltd., which thermally decomposes at 130–157°C and releases 160–180 ml/g of gas, contributing to the formation of a fine cellular structure within the foam.

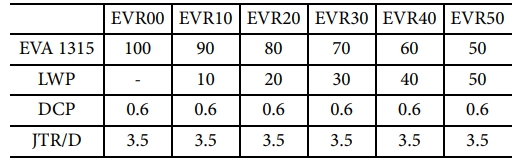

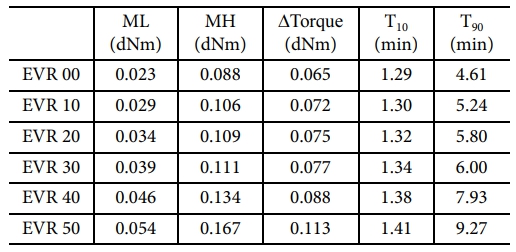

To investigate the effect of LWP content on the foaming characteristics of EVA, experiments were conducted by adjusting the LWP content. EVA and LWP were blended in weight ratios ranging from 100:0 to 50:50, increasing by 10 wt% increments, resulting in six different compositions. The compositions are shown in Table 1. For each blend, the same amount of crosslinking agent and blowing agent was added, and compression molding was performed at 170°C for 10 minutes under pressure to produce the foam samples, EVA-based recycled foams (EVR).

2.2 Characteristics

The crosslinking characteristics of the samples were measured using an Oscillating Disk Rheometer (ODR, Curelastometer WR, Nichigo Shoji Co., Japan, Max torque 30 N·m) at 170°C for 20 minutes. The process of measuring the crosslinking characteristics is essential for determining the optimal molding time and degree of crosslinking, as these factors greatly influence the final shape and mechanical properties of the molded products.

Specific gravity was measured using an electronic densimeter (MD-300S, Alfa Mirage), and the foaming ratio was calculated using the following equation:

where Vf and Vm represent the volume of the foamed material and the mold, respectively.

The tensile properties of the samples were measured using a dumbbell-shaped specimen with dimensions of 10.0 × 50.0 mm (width × length) with a Universal Testing Machine (UTM, Daekyung Engineering, DUT-500CM, South Korea, Max 500 kgf). The test speed was set at 500 mm/min, and the gauge length was 20 mm. Tensile strength and elongation were measured simultaneously. Tear strength was also measured under the same conditions.

Hardness was measured using a Durometer C-type from Asker. Additionally, the ball rebound resilience of the foam was recorded according to the KS M ISO 8307 standard by measuring three times and recording the median value.

The compression set of the foam, which evaluates its durability, was calculated by measuring the thickness after compressing the sample in a 50°C oven for 6 hours. The formula for calculating the compression set is as follows:

where t0 represents the initial thickness, tl represents the thickness after the test, and ts represents the compressed thickness.

To observe the microstructure of the foam, images were captured using the Xi-cam video microscope from Bestecvision.

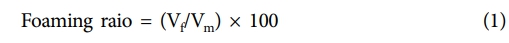

3.1 Crosslinking Characteristics

Fig. 1 and Table 2 present the results of the crosslinking characteristics of EVA and EVA/LWP foams measured using an ODR. The scorch time (T10) was approximately 1 minute, and it showed minimal variation with increasing LWP content, indicating that the initial crosslinking reaction was not significantly affected.

In contrast, The optimum cure time (T90), which represents the progress of crosslinking, increased from 4.61 minutes to 9.27 minutes as the LWP content increased, nearly doubling. This suggests that the lower reactivity of LWP compared to EVA slowed the crosslinking reaction.

Additionally, both the minimum torque (ML) and maximum torque (MH) values increased with higher LWP content, and ΔTorque (MH - ML) also exhibited a gradual increase. ΔTorque is generally closely related to crosslink density [11], indicating that LWP contributes to increasing crosslink density.

LWP is a previously crosslinked recycled EVA foam, with a molecular weight distribution and crystallinity differ from those of neat EVA. In addition this suggests that the residual cross-linked structure, which was not completely decomposed, formed microgels, contributing to the increase in ΔTorque.

The increase in T90 demonstrates the slower reactivity of LWP compared to EVA, while the increase in ΔTorque suggests that, despite the delayed reaction, more crosslinking bonds were formed, or the network structure was strengthened.

Since the torque values of all samples stabilized after 10 minutes, a foaming time of approximately 10 minutes was set for foam production in this study.

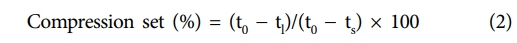

3.2 Foaming Characteristics

The specific gravity and foaming ratio are important indicators of the lightweight characteristics and foaming properties of polymeric foams. Fig. 2 presents the foaming ratio and specific gravity of EVA and EVA/LWP composite foams.

The foaming ratio of pure EVA foam (EVR00) was measured at 164%, and as the LWP content increased, the foaming ratio gradually decreased. EVR 10, 20, 30, 40 and 50 were 162, 160, 159, 155 and 151%, respectively. This indicates that the foaming properties deteriorated with the addition of LWP.

The specific gravity of the foams showed an opposite trend. The specific gravity of EVR 00 was the lowest at 0.155, and as the LWP content increased, it has increased gradually. EVR 10, 20, 30, 40 and 50 were 0.166, 0.172, 0.180, 0.190, and 0.208, respectively.

The specific gravity and foaming ratio exhibited an inverse relationship, with the specific gravity increasing as the foaming ratio decreased. This trend highlights the impact of LWP addition on the foaming characteristics and the lightweight properties of the foams.

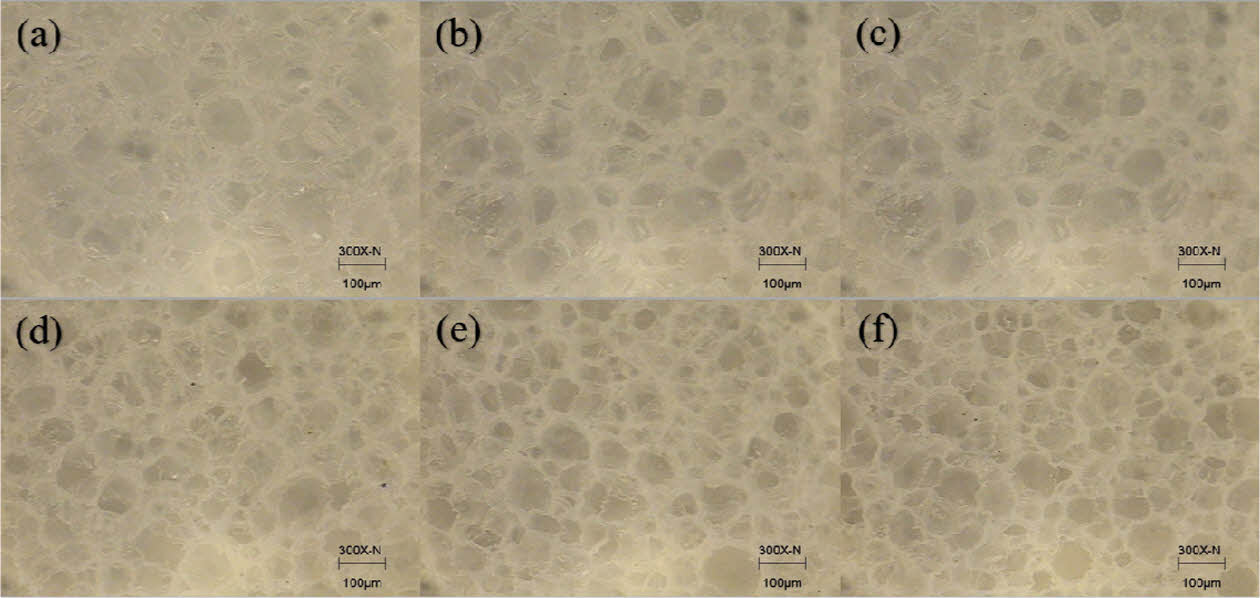

Fig. 3 illustrates the changes in cell structure with increasing LWP content, as observed in cross-sectional images of the foams taken with an optical microscope.

As the LWP content increased, the cell size gradually decreased, the cell wall thickness reduced, and the non-uniformity in cell size and shape increased. Along with the previous ODR results, it suggests that LWP can act as a nucleating agent. The crystalline particles remaining in LWP serve as hetero-nucleating sites, facilitating foam density control.

These structural changes contributed to the increase in specific gravity, ultimately limiting the lightweight properties of the foams.

3.3 Mechanical Properties

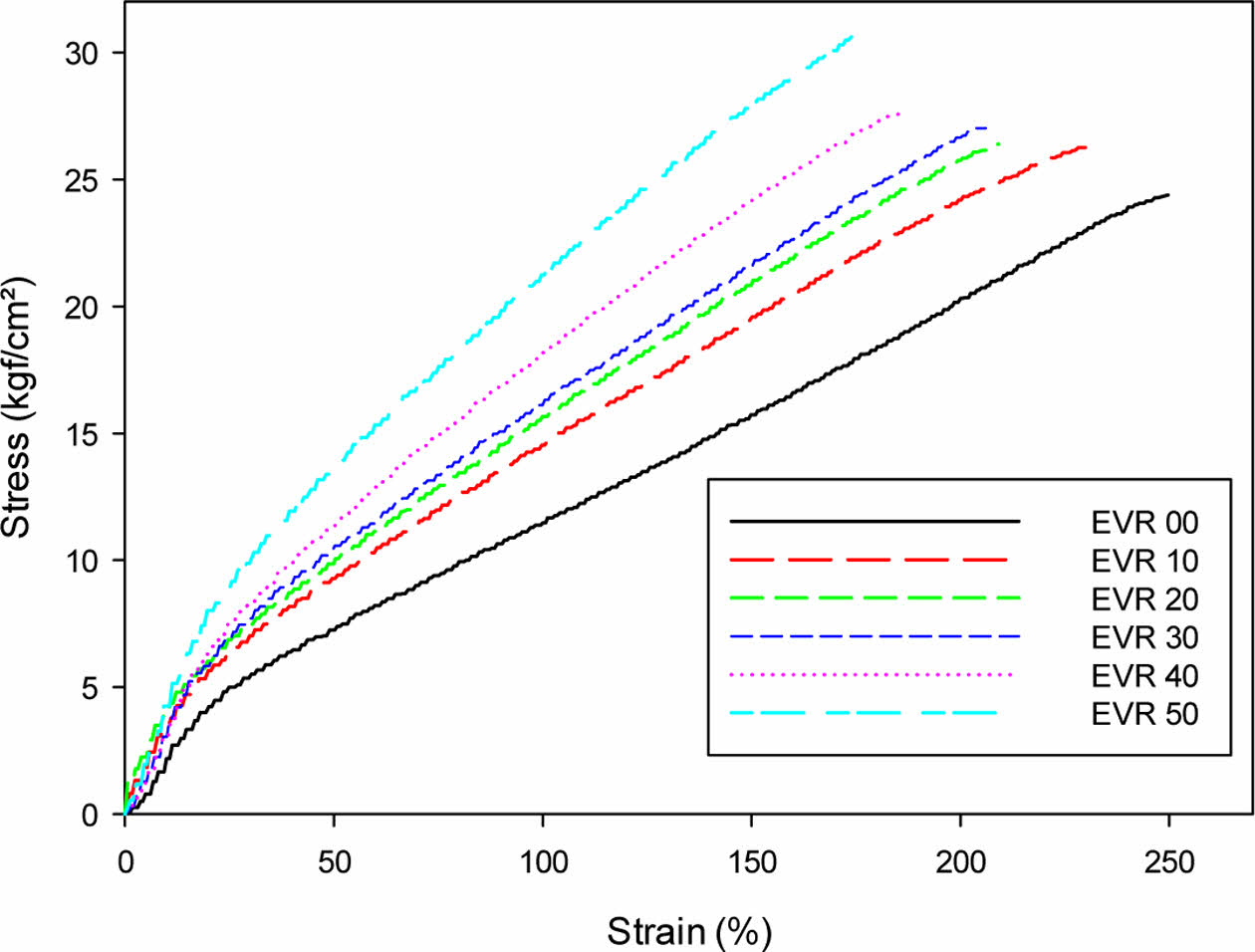

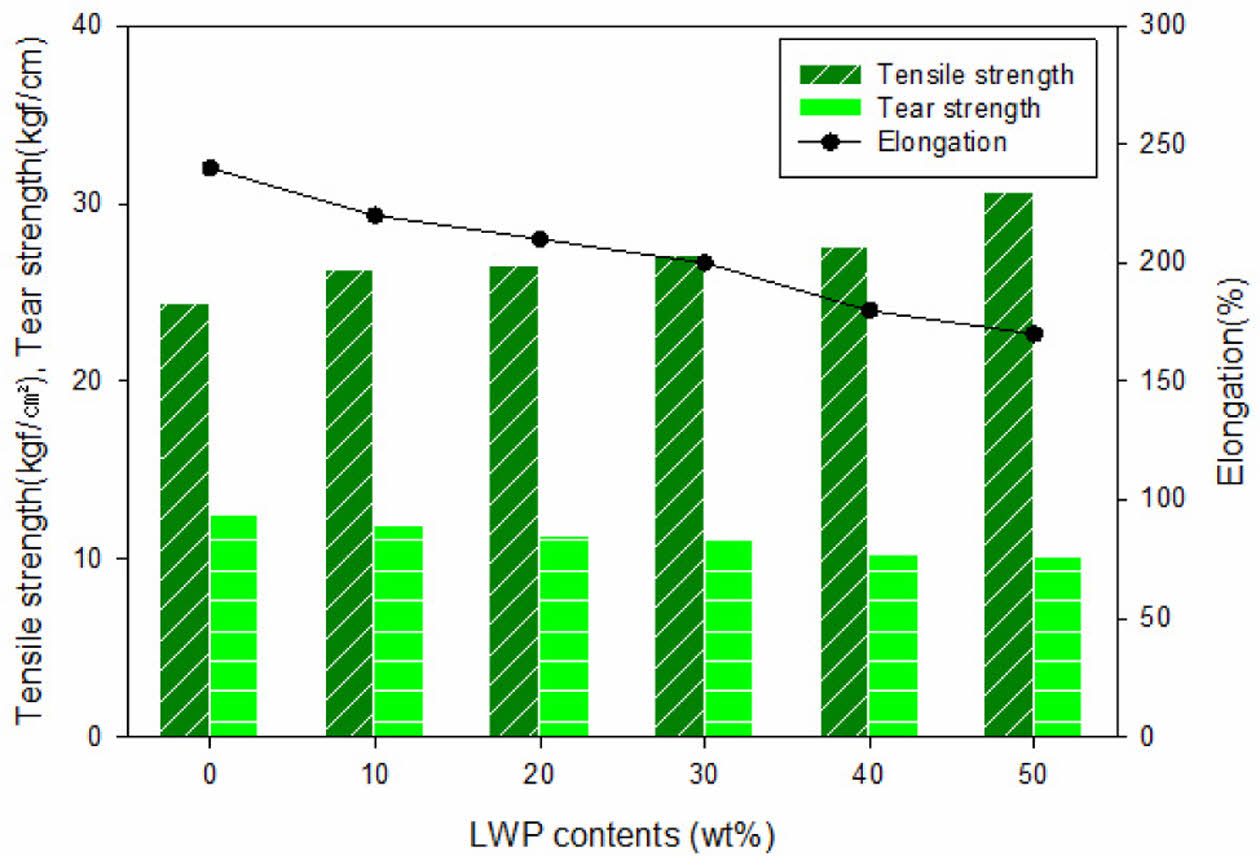

Figs. 4 and 5 present the S-S curve, tensile strength, elongation at break, and tear strength of EVA and EVA/LWP composite foams.

As the LWP content increased, the tensile strength showed a tendency to increase by up to approximately 25%. This can be attributed to the increased crosslink density of the EVA/LWP composite foams as the LWP content increased, as confirmed by the crosslinking characteristics analysis.

Conversely, the elongation at break decreased from 240% for EVR 00 to 170% for EVR 50, representing a reduction of about 30%. Tear strength also showed a decreasing trend, with a maximum reduction of 20%. These tendencies appear to be caused by phase separation between LWP and EVA. Phase separation disrupts the uniform formation of cells during the foaming process, resulting in smaller cell sizes or non-uniform structures. These changes in cell structure are corroborated by the microscopic images.

Meanwhile, the increase in tensile strength seems to be primarily influenced by the rise in crosslink density, with the increase in specific gravity also likely playing an additional role. The higher crosslink density strengthened the internal bonds within the material during the foaming process, leading to improved tensile strength. However, phase separation caused by the increased LWP content weakened the material’s continuity, resulting in a reduction in elongation at break and tear strength. This explains the contrasting trend of increasing tensile strength alongside decreasing elongation at break and tear strength.

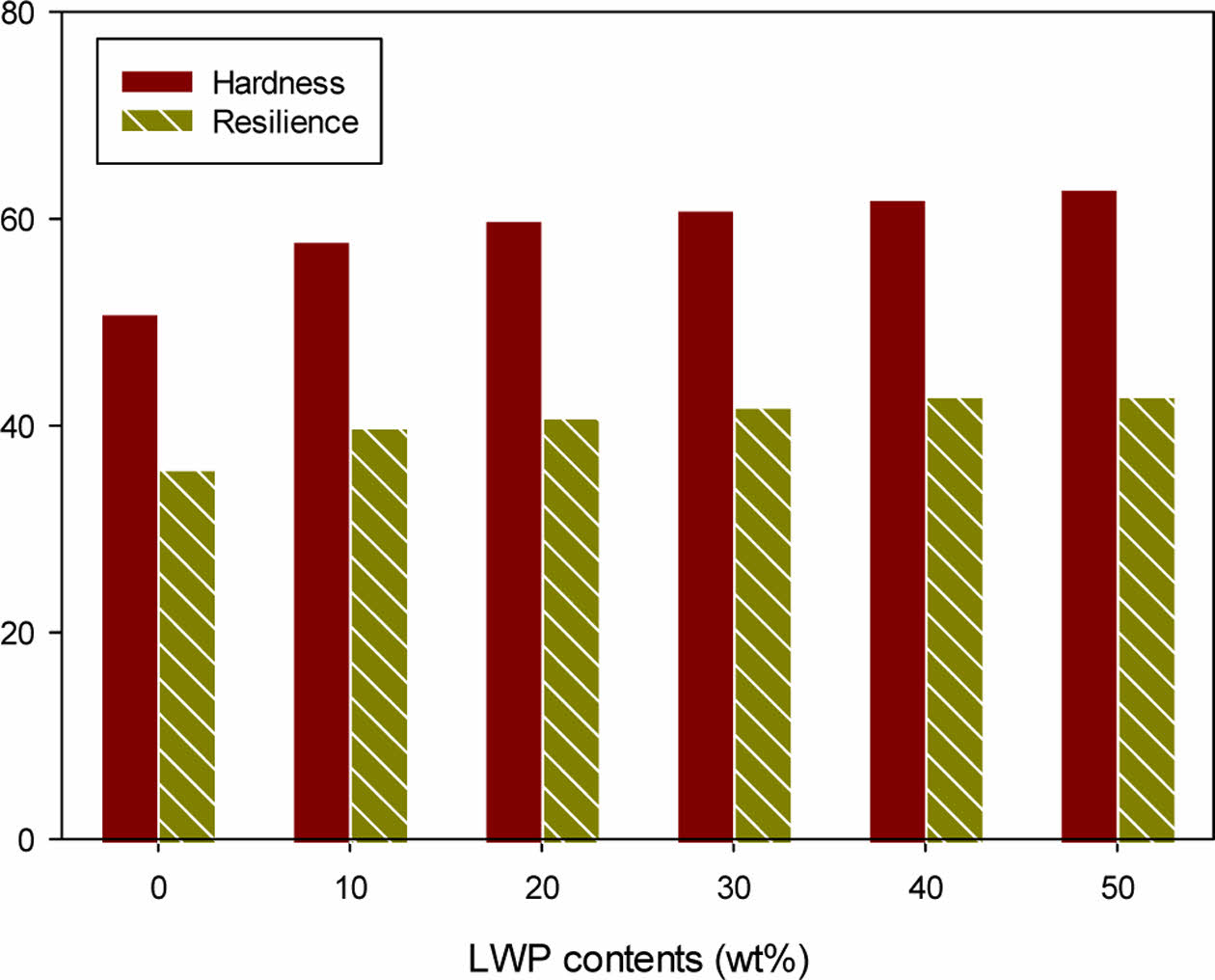

Additionally, the hardness and rebound resilience (ball rebound resilience) of each foam were measured, and the results are shown in Fig. 6. The experimental results revealed that both hardness and rebound resilience increased as the LWP content increased. This trend is attributed to the rigid properties of LWP compared to EVA, which made the material overall stiffer as the LWP content increased. Moreover, the addition of LWP contributed to an increase in crosslink density, which is interpreted as a key factor in the improvements in hardness and rebound resilience.

The increase in hardness can be explained by the reinforcement of the polymer network caused by the rigid characteristics of LWP and the higher crosslink density, enabling the foam to resist external deformation more effectively. Meanwhile, the increase in rebound resilience is attributed to the well-formed crosslinking structure within the EVA/LWP blend, allowing for efficient recovery of impact energy.

Furthermore, the phase separation between LWP and EVA appears to play a role, with the rigid phase (LWP) acting as the primary contributor, promoting the simultaneous increase in hardness and rebound resilience. However, these positive changes in properties are accompanied by negative effects, such as reductions in elongation at break and tear strength, indicating that the material properties of the foam have changed in a complex manner.

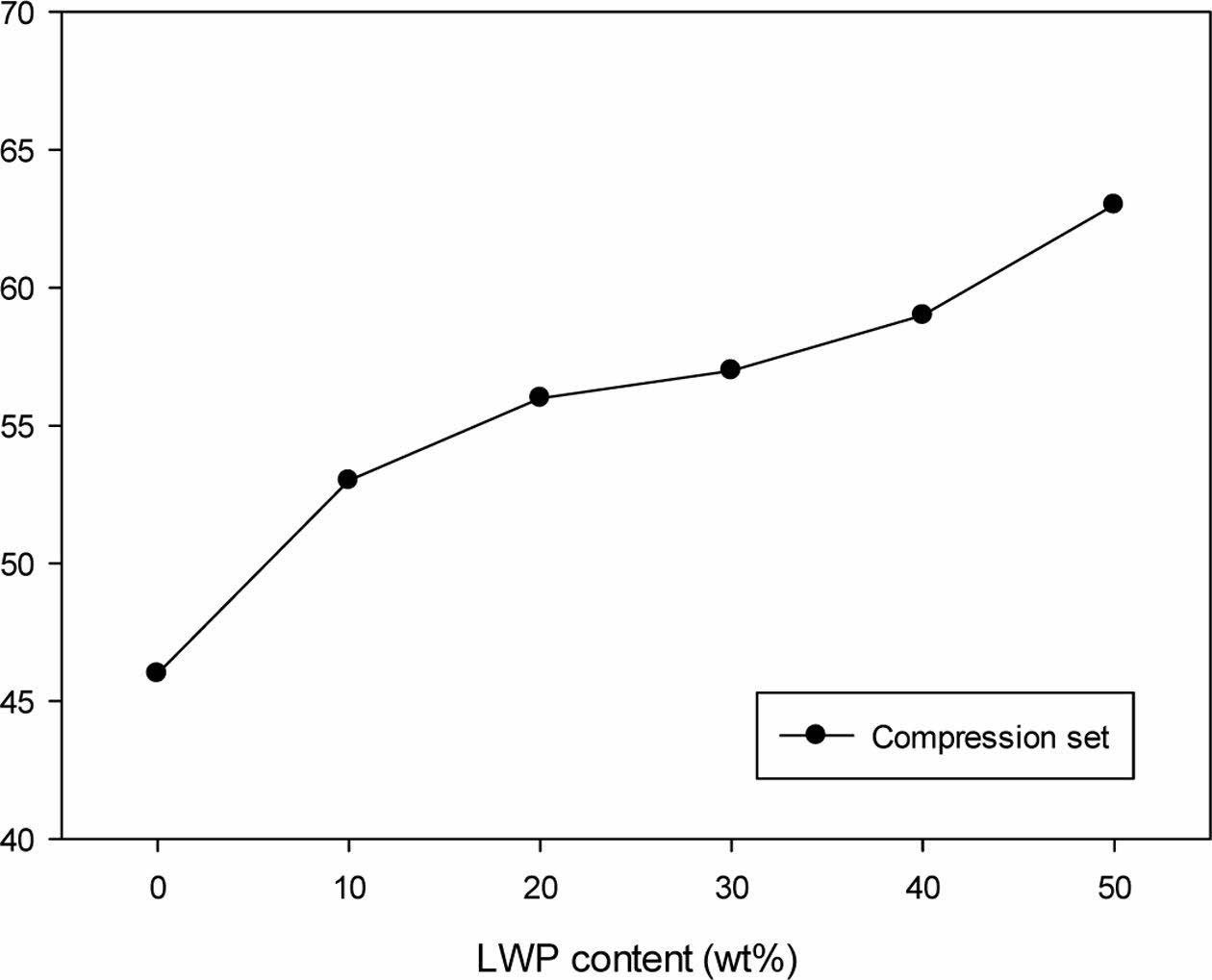

The permanent compression set of each foam was measured, and the results are presented in Fig. 7. The data showed that as the LWP content increased, the permanent compression set value also increased. This indicates a deterioration in the foam’s recovery performance and an increase in permanent deformation after compression.

The increase in LWP content likely resulted in higher crosslink density, which reduced the material's flexibility and limited its ability to adapt to compressive deformation. These changes made the material stiffer but simultaneously weakened its recovery capacity under external loads, leading to more pronounced permanent deformation.

In conclusion, the recovery performance of EVA/LWP composite foams decreased with increasing LWP content, which is interpreted as the result of structural changes and non-uniformity within the material.

|

Fig. 1 Crosslinking behaviors of the EVA and EVA/LWP composite foams |

|

Fig. 2 Foaming ratio and Density of EVA and EVA/LWP foams |

|

Fig. 3 Morphologies on the cross section of the EVA and EVA/ LWP composite foams; (a) EVR 00, (b) EVR 10, (c) EVR 20, (d) EVR 30, (e) EVR 40, (f) EVR 50. The scale bar is 100 μm |

|

Fig. 4 Strain-stress curves of EVA and EVA/LWP composite foams |

|

Fig. 5 Tensile strength, Tear strength and Elongation of EVA and EVA/LWP composite foams |

|

Fig. 6 Hardness and Resilience of EVA and EVA/LWP composite foams |

|

Fig. 7 Compression Set of EVA and EVA/LWP composite foams |

This study evaluated the effects of lightweight waste plastic (LWP) content on the foaming characteristics, crosslinking properties, and mechanical performance of EVA (ethylene-vinyl acetate) blend foams. The experimental results showed that as the LWP content increased, the foaming ratio decreased while the specific gravity of the foam increased, indicating a deterioration in foaming properties. This suggests that the lightweight characteristics of the foam are limited by the addition of LWP, which was accompanied by observations of denser cell structures and reduced cell sizes.

According to ODR measurements, the crosslink density increased with higher LWP content, contributing to improved tensile strength and mechanical stability. However, phase separation between EVA and LWP appeared to reduce elongation at break and tear strength, reflecting the complex interplay between increased crosslink density and phase separation.

Mechanical property analysis revealed that hardness and rebound resilience improved with increasing LWP content, which aligned with the observed increase in tensile strength. However, the permanent compression set also increased, indicating a decline in recovery performance after compression. This is attributed to reduced material flexibility as LWP content increased, thereby limiting the foam's recovery capacity.

In conclusion, while the addition of LWP enhances certain mechanical properties such as tensile strength and hardness, it is accompanied by issues such as reduced foaming performance and recovery ability. Nevertheless, the recyclability of EVA/LWP blends and the potential application of waste plastics in foam production present a promising avenue for the development of sustainable materials. In addition, through the appropriate mixing ratio of LWP (10-20 wt%), it might function as a functional filler.

- 1. Henderson, A.M., “Ethylene-Vinyl Acetate (EVA) Copolymers: A General Review,” IEEE Electrical Insulation Magazine, Vol. 9, No. 1, 1993, pp. 30-38.

-

- 2. Ercan, N., and Korkmaz, E., “Structural, Thermal, Mechanical and Viscoelastic Properties of Ethylene Vinyl Acetate (EVA)/Olefin Block Copolymer (OBC) Blends,” Materials Today Communications, Vol. 28, 2021, Article ID 102634.

-

- 3. Almeida, A., Possemiers, S., Boone, M.N., De Beer, T., Quinten, T., Van Hoorebeke, L., Remon, J.P., and Vervaet, C., “Ethylene Vinyl Acetate as Matrix for Oral Sustained Release Dosage Forms Produced via Hot-Melt Extrusion,” European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, Vol. 77, 2011, pp. 297–305.

-

- 4. Alothman, O.Y., “Processing and Characterization of High Density Polyethylene/Ethylene Vinyl Acetate Blends with Different VA Contents,” Advance in Materials Science and Engineering, Vol. 2012, No. 1, 2012, pp. 1-10.

-

- 5. McLoughin, K.M., Oshouei, A.J., Sing, M.K., Bandegi, A., Mitchell, S., Kennedy, J., Gray, T.G., and Manas-Zloczower, I., “Thermomechanical Properties of Cross-Linked EVA: A Holistic Approach,” ACS Applied Polymer Materials, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2023, pp. 1430-1439.

-

- 6. Zhao, D., Xia, M., Shen, Y., and Wang, T., “Three-dimensional Cross-linking Structures in Ceramifiable EVA Composites for Improving Self-supporting Property and Ceramificable Properties at High Temperature,” Polymer Degradation and Stability, Vol. 162, 2019, pp. 94-101.

-

- 7. Rosa, V.B., Zattera, A.J., and Poletto, M., “Evaluation of Different Mechanical Recycling Methods of EVA Foam Waste,” Journal of Elastomers & Plastics, Vol. 53, 2021, pp. 1–20.

-

- 8. Ergin, M.F., and Aydin, I., “Evaluation of Rheological Behaviour upon Recycling of an Ethylene Vinyl Acetate Copolymer by Means of Twin-Screw Extrusion Process,” Acta Physica Polonica A, Vol. 131, 2017, pp. 542-544.

-

- 9. Rodriguez-Perez, M.A., Simoes, R.D., Roman-Lorza, S., Alvarez-Lainez, M., and Montoya-Mesa, C., “Foaming of EVA/starch Blends: Characterization of the Structure, Physical Properties, and Biodegradability,” Polymer Engineering & Science, Vol. 52, No. 1, 2012, pp. 62-70.

-

- 10. Girija, B.G., Sailaja, R.R.N., Sharmistha B., and Deepthi, M.V., “Mechanical and Thermal Properties of EVA Blended with Biodegradable Ethyl Cellulose,” Journal of Applied Polymer Science, Vol. 116, No. 2, 2010, pp. 1044-1056.

-

- 11. Choi, S.S., and Chung, Y.Y., “Considering Factors for Analysis of Crosslink Density of Poly(ethylene-co-vinyl acetate) Compounds,” Polymer Testing, Vol. 66, 2018, pp. 312–318

-

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 38(5): 604-609

Published on Oct 31, 2025

- 10.7234/composres.2025.38.5.604

- Received on Sep 6, 2025

- Revised on Sep 23, 2025

- Accepted on Oct 29, 2025

Services

Services

- Abstract

1. introduction

2. experimental details

3. result and discussion

4. conclusions

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Donghun Han

-

Korea Institute of Materials Convergence Technology, Busan 47154, Republic of Korea

- E-mail: dhhan@kimco.re.kr

Copyright ⓒ The Korean Society for Composite Materials. All rights reserved.

Copyright ⓒ The Korean Society for Composite Materials. All rights reserved.