- A Study on the Development of Textile Electrodes for Body Contact Sensing for High-reliability Smartwear

Jong-hyun Joo*, Seong-Hwang Kim*, Hye-ji Jeon*, Ju-Ra Jeong*, Jin-seok Bae**† , Ri-ra Kim***†

* Korea Institute of Convergence Textile (KICTEX)

** Department of Textile System Engineering, Kyungpook National University, Daegu 37224, Korea

*** Corresponding author (E-mail: jbae@knu.ac.kr) Department of Lifestyle Design, Yuhan University, KoreaThis article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Conductive fabrics can be used for a variety of purposes and have the advantage of being soft and flexible, allowing for easy collection of personal body change data from the closest position on the body. Among various biosignals, EMG and ECG are the most commonly collected and fundamental biosignal information. To accurately acquire wearable EMG and ECG data, the role of electrodes is crucial. Currently, biosignal monitoring is primarily performed using wet electrodes; however, they have disadvantages such as skin damage from prolonged use, discomfort from attachment and detachment, and being single-use and non-washable. Therefore, for healthcare consumers and patients, there is a need for wearable electrodes capable of long-term monitoring of biosignals, and gel-free dry electrodes, and ultimately, conductive textile electrodes are seen as alternatives to traditional wet electrodes in clothing-type wearable smart devices. This study focuses on researching high-reliability electrodes for stable biosignal acquisition by using silver, a material with excellent conductivity, to coat fabric and create conductive fabric. A dry-type fiber electrode was then created using the selected final conductive fabric. The fabricated fiber-type dry electrode was evaluated through comparative tests on its basic electrical properties, durability against stretching and tearing when applied to the human body, tactile performance on the skin during wear, resistance changes due to folding and creasing during activity, performance changes during washing, and performance variations in extreme temperature and humidity conditions. Through this evaluation, the reliability of the electrode’s applicability to clothing-type wearable smart devices for biosignal acquisition was confirmed, and the potential for its practical use was explored.

Keywords: Textile electrodes sensor, Smartwear, Dry electrode, Fast-fourier

With the advancement of Information and Communications Technology (ICT), smart textile products that incorporate electrical, electronic, and communication technologies have been developed and applied in various fields. Particularly, as interest in exercise and health management has increased, the demand for healthcare wearable smart devices has grown, leading to research and development of smart textiles for wearable devices that offer advantages in user activity and convenience. Wearable smart devices are defined as devices that can be worn or attached to the body without interfering with the wearer’s habits or consciousness and have the ability to connect with external systems for communication, enabling various intelligent processing and user interaction [1]. Wearable smart devices have evolved from accessory-type devices to integrated clothing, with further development in body-attachment and bio-implantable devices. In the case of clothing-integrated devices, the technology has evolved from attaching rigid devices to fabrics to incorporating sensor functions directly into the clothing itself. Since these devices are fabric-based, they offer advantages such as flexibility, lightweight properties, and stretchability. One of the key technologies for clothing-type wearable devices is conductive textiles. Conductive fibers are fabrics with reduced electrical resistance, made from materials such as metal semiconductors, carbon black, and metal oxides. The electrical properties of conductive fibers form the foundation of smart textile applications, and depending on the electrical resistivity and physical and chemical properties of each fiber, they can be applied to various functional products. Key technologies for manufacturing conductive fibers include conductive yarn (conductive thread) manufacturing technology, conductive fabric and knitting technology, and conductive material post-processing technology. Conductive fibers can be used for various purposes, and their softness and flexibility allow for easy collection of personal body change data from the closest position on the body [2]. Recently, research has been actively conducted on monitoring subtle body movements, such as blink rate, pulse, and respiration, using fiber-based strain sensors or graphene woven fabrics (GWF). In particular, after COVID-19, devices that measure biosignals such as blood sugar, blood pressure, body temperature, and heart rate have gained significant attention, and research on wearable biosignal monitoring devices for everyday use is being conducted globally [3,4]. Among various biosignals, the most commonly collected and basic biosignals are electromyography (EMG), which measures the potentials generated by skeletal muscles, and electrocardiography (ECG), which records the electrical activity of the heart in waveform form. To accurately measure these biosignals, the role of electrodes is crucial [4,5].

Currently, biosignal monitoring is primarily performed using wet electrodes, which use adhesive pads (Ag/AgCl gel) to optimize electrode-skin contact impedance and ensure stable contact between the conductive gel and the skin. However, wet electrodes have limitations for long-term monitoring due to skin damage caused by prolonged use, and their strong adhesive properties make them uncomfortable to attach and detach after every use. Additionally, they are single-use and cannot be washed. Wearable smart devices must offer users the freedom to move and be discreet in daily life, and depending on the materials used, they should provide comfort and enable long-term, continuous biosignal monitoring [2,3]. As a result, there is increasing attention on gel-free dry electrodes for long-term biosignal monitoring in wearable devices for healthcare consumers and patients, and conductive textile electrodes are being evaluated as alternatives to traditional wet electrodes in clothing-type wearable smart devices [6,7].

Therefore, this study focuses on developing high-reliability electrodes for stable biosignal acquisition by using silver, a material with excellent conductivity, to coat fabric and create conductive fabric, and then making dry-type fiber electrodes. The fabricated fiber-type dry electrodes were evaluated through comparative tests on their basic electrical properties, durability against stretching and tearing during human application, tactile performance on the skin during wear, resistance changes due to creasing and folding during activity, performance changes during washing, and performance variations in extreme temperature and humidity conditions. Through this evaluation, the study aimed to verify the reliability and explore the feasibility of applying the electrodes to clothing-type wearable smart devices for biosignal acquisition, considering the interactions between various factors.

2.1 Materials

Nylon fabrics (10-inch width, 25-inch length, 0.2 mm thickness) was purchased from Bogwang Co., Korea. The silver ntrate (AgNO3, purity: >99.8%) was purchased from DaeJung Co., Korea. Nitric acid (HNO3, analytical grade) was purchased from DaeJung Co., Korea. Palladium chloride (PdCl2) and tin (II) chloride (SnCl2) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co., USA.

2.2 Surface modifications

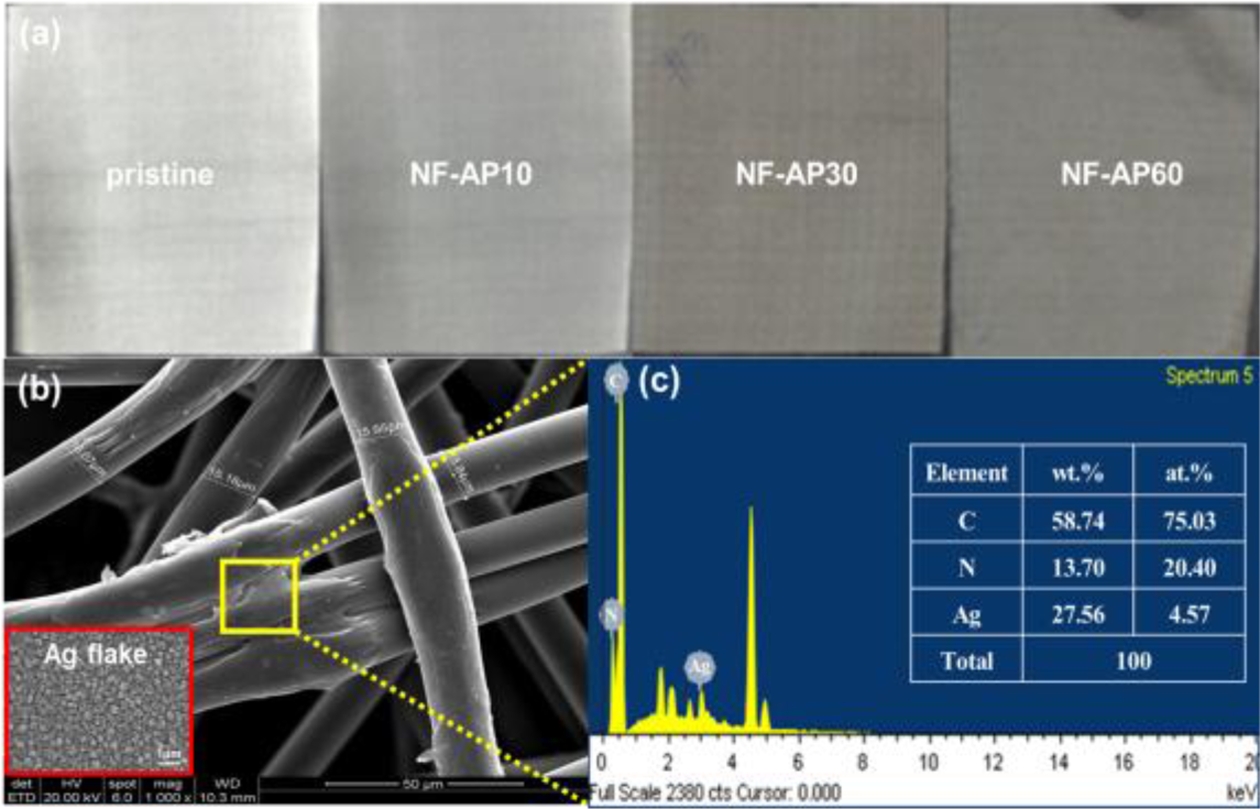

Nylon fabric was added into a mixture of sulfuric acid and nitric acid (4:1 vol ratios). After reacting for 15 min, the nylon fabric obtained by filtration was washed with distilled water until a neutral pH was achieved, and then dried in a vacuum oven at 80°C for 8 h. After drying the activated nylon was treated in a tin chloride (SnCl2) and palladium chloride (PdCl2) activation solution to form Sn/Pd nuclei for silver (Ag) reduction. The Ag coated nylon fabric was obtained by immersing the treated nylon fabric for 10 min in a Ag bath (pH: 8.5, temperature: 25°C). The diameter of Ag particles on the nylon surface is about from 600 nm to 1.2 µm. The structures of the Ag coated nylon fabrics are revealed by the High-resolution scanning electron microscopy (HR-SEM) and Energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS) images in Fig. 1.

2.3 Fabrication of the fiber-type dry electrode

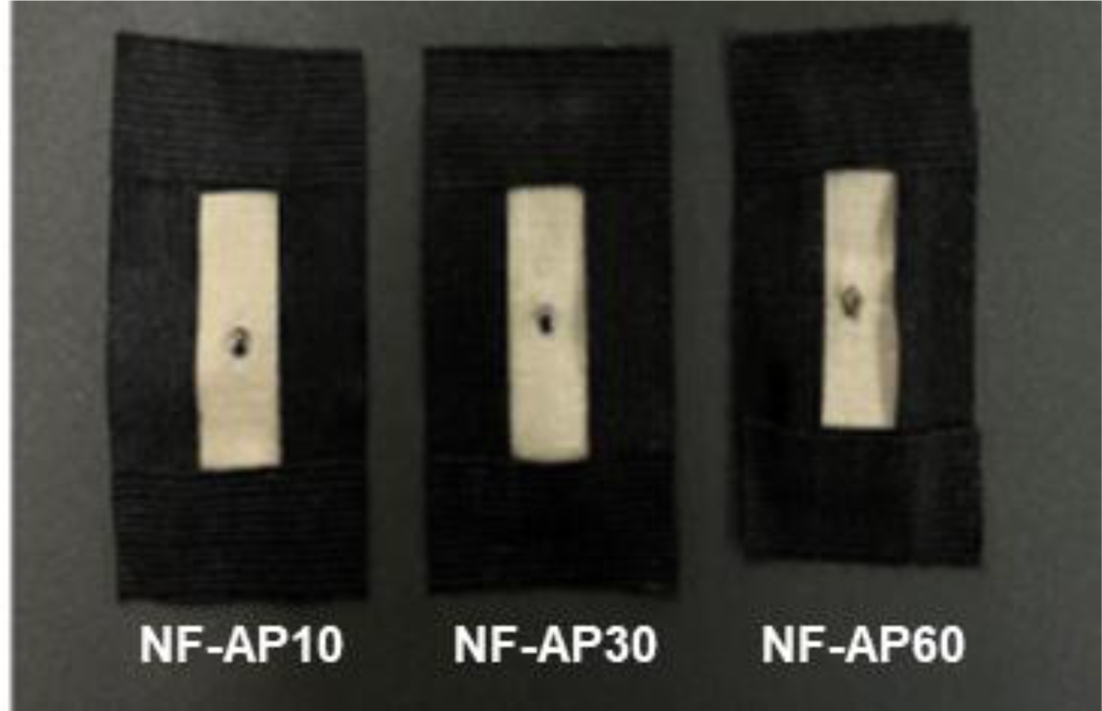

The sensing electrodes used in this experiment were fabricated using the following types of fabrics. We denoted the conductive fabrics of Ag-treated nylon for 10 min, 30 min, and 60 min as NF-AP10, NF-AP30, and NF-AP60, respectively (Fig. 2), where the time indicates the Ag coating duration. Based on the results of the material property analysis, the NF-AP30 was selected as the final material for fabricating the fiber-type dry electrode for human sensing verification. The fabrication process of the fiber-type dry electrode is as follows: Two pieces of NF-AP30 were cut into rectangular sheets measuring 2.5 cm × 5 cm each. Prior to assembly, the conductive fabrics were cleaned with ethanol and dried at 60°C for 2 h to remove contaminants. A metal snap attachment was affixed to the 1-layer of the conductive fabric using a press to ensure reliable electrical contact. A 2-layer composite was then added beneath the first layer to enhance stability and ensure a structure similar to conventional wet electrodes. The electrode was shaped into a form that closely resembles commercial wet electrodes, allowing for easy integration into wearable devices for human biosignal sensing.

2.4 Characterization

The linear resistance(Ω) measurement was conducted using an LCR meter (KESIGHT) to evaluate changes in the electrical properties of the conductive fabric [8]. The resistance (R) values over a 10 cm distance were measured five times using the two probes of the LCR meter, and the average value was calculated. The sheet resistance (Ω/sq) was measured using a 4-Point Probe-HS 8(DASOL ENG) to assess changes in the electrical properties. The wash durability test was conducted in accordance with the KS K ISO 6330 standard for three types of conductive fabrics. The washing conditions involved adding 1.33 g/L of standard soap (Test Fabrics, Inc.) and 10 beads for each sample, followed by 20 wash cycles (1 cycle/10 minutes) using an IR washer. To investigate the changes in electrical resistance of textile electrodes, a sheet resistance measurement device was used to compare and analyze the electrical properties before and after exposure to high-temperature and high-humidity conditions. Electrical resistance changes of the textile electrodes subjected to 10,000 bending and twisting cycles were analyzed using a multi-purpose flexible device tester (Multi Tester, CKSI). Sheet resistance was measured five times before and after the cycling to assess resistance variation. To evaluate the tensile strength and elongation of conductive fabrics based on their weave structures, tests were conducted using a Universal Testing Machine (Instron 5567, Instron) in accordance with the KS K 0520 (Graphical Method) standard. Test specimens measuring 100 × 150 mm were prepared, with five samples each in the warp and weft directions. The specimens were set with a gauge length of 76 mm on the constant-rate extension tester, and the extension speed was set to 100 mm/min. The surface characteristics of the fabrics were analyzed using the Kawabata Evaluation System for Fabric (KES-FB, Kato Tech. Co. Ltd.), as outlined in the table below. The specimens for measurement were prepared in dimensions of 20 × 20 cm and evaluated in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment (20°C, 65% RH) under standard testing conditions. To validate human sensing, the EMG signals of conventional Ag-AgCl wet electrodes for medical use, manufactured by 3M, were compared with those of Ag-coated nylon-based dry electrodes. The EMG signals were analyzed by comparing the signal data generated during muscle activation (contraction and relaxation) of the forearm muscles.

|

Fig. 1 Surface morphology of Ag-coated nylon fabric: (a) optical images, (b) SEM images and (c) EDS data |

|

Fig. 2 Optical images of the Ag-coated nylon electrode |

3.1 Electrical properties of Ag-coated nylon electrode

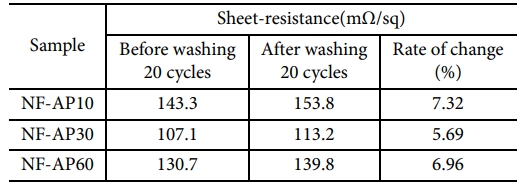

To evaluate the durabilityof electrode fabrics, the sheet resistance before and after washing were compared and analyzed. NF-AP30 coated with Ag exhibited the lowest resistance values in terms of sheet resistance, as shown in Table 1. In conclusion when comparing before and after 20 washing cycles, the NF-AP30 with coated Ag not only demonstrated the lowest resistance but also exhibited excellent durability. However, the NF-AP60 sample showed a higher sheet resistance compared to NF-AP30, which can be attributed to particle agglomeration caused by the prolonged Ag coating time, leading to a less uniform conductive layer and reduced electrical pathways.

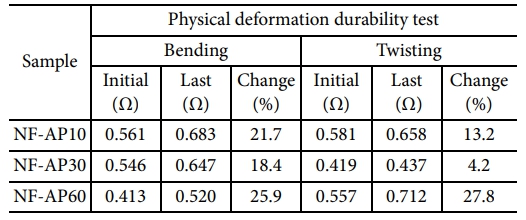

The analysis of resistance changes under repeated deformation revealed that the electrical resistance of all textile-based electrode fabrics increased with 10,000 cycles of physical deformation (bending and twisting), as shown in Table 2. These results suggest that the electrical resistance of textile electrodes increases as mechanical fatigue accumulates. Among the fabrics, the one with the smallest resistance change rate after repeated bending and twisting was NF-AP30, which contained embedded copper threads, showing change rates of 18.4% and 4.2%, respectively.

3.2 Mechanical properties of Ag-coated nylon electrode

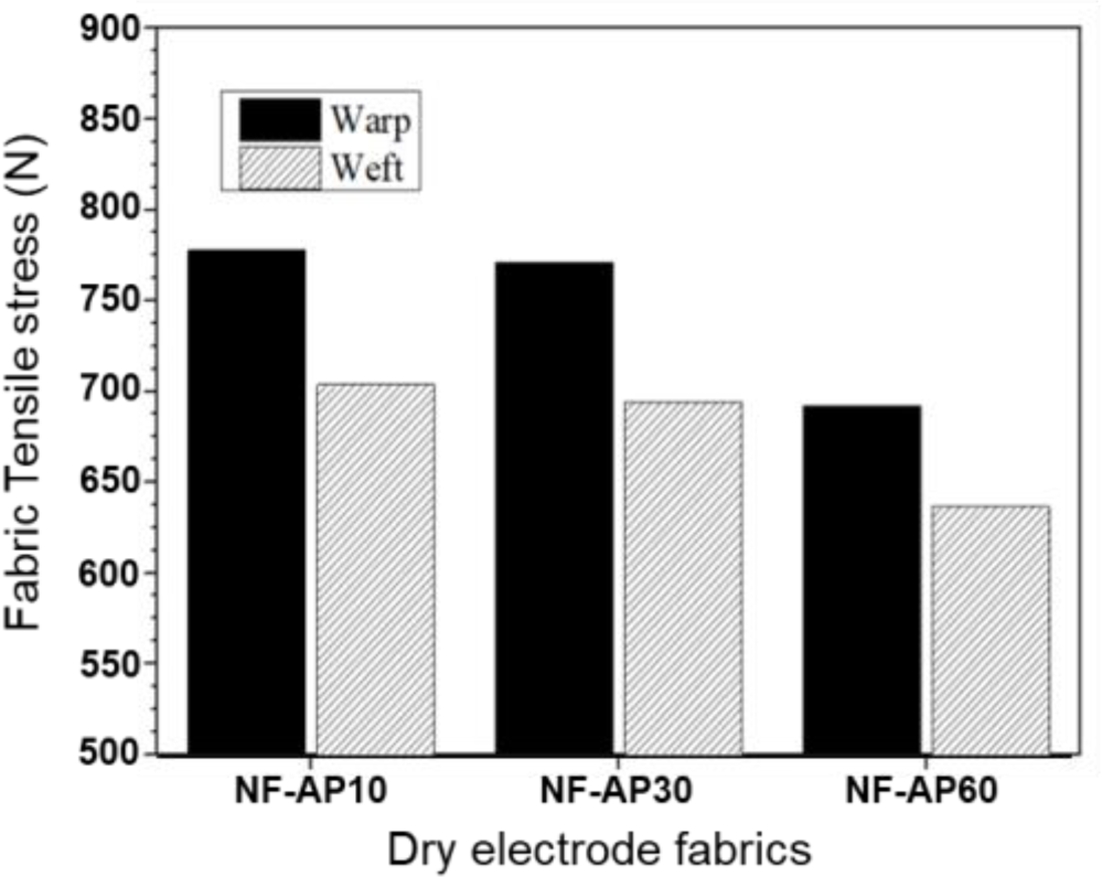

Analysis of the tensile strength of the three types of conductive fabrics demonstrated that NF-AP10, which possessed the highest fabric density, exhibited the greatest tensile strength. This finding suggests that the inclusion of coated Ag does not inherently enhance the tensile properties of the nylon fabric.

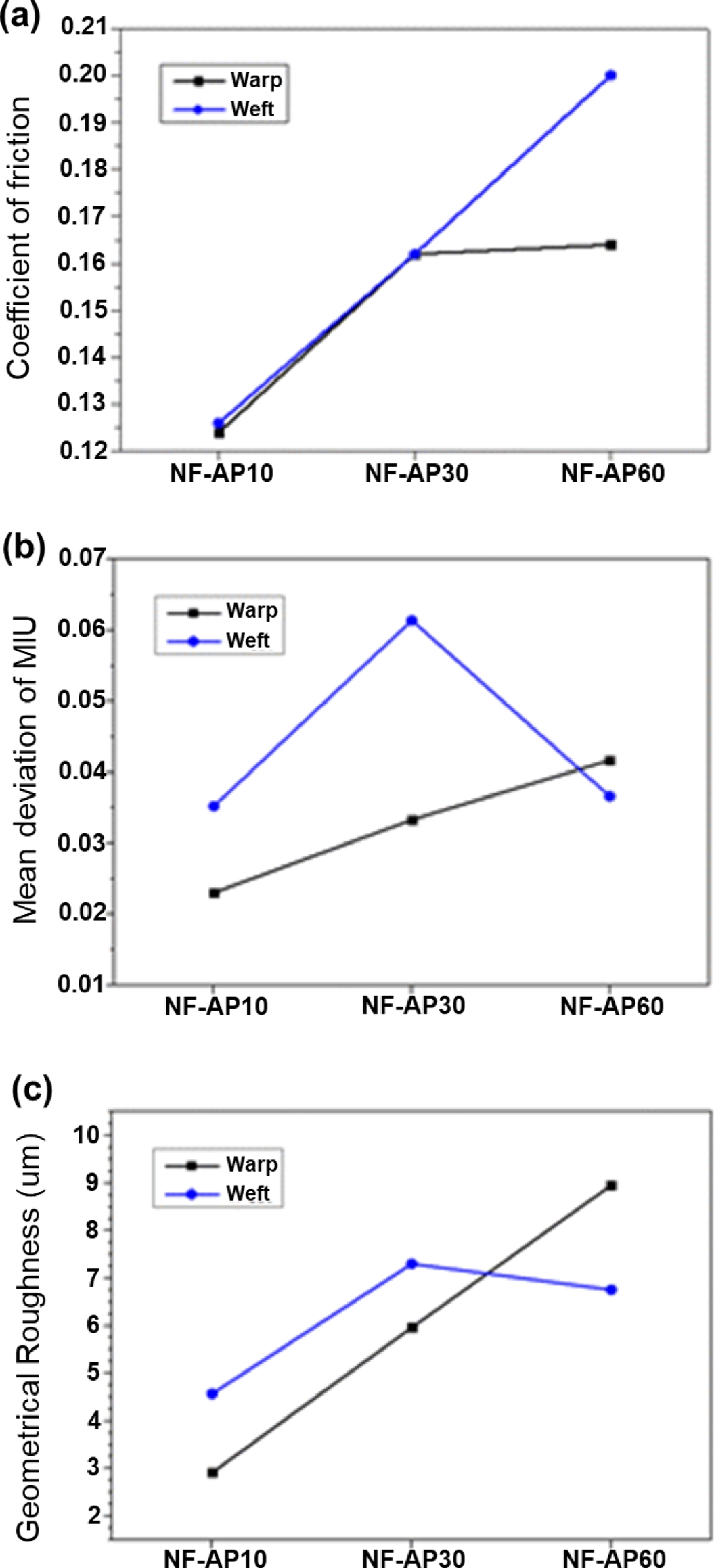

The results of the tactile property analysis of textile materials for electrodes are shown in Fig. 4. Lower values of the coefficient of friction (MIU), mean deviation of friction (MMD), and surface roughness (SMD) indicate a smoother surface with more uniform friction. Surface Property is related to the Smoothness of Fabrics. As shown in Fig. 4(a), the mean MMD was nearly identical for NF-AP10 and NF-AP30 in both the warp and weft directions. The MIU was lowest for Electrode NF-AP10 in both warp and weft directions, suggesting that its surface is smooth and has uniform friction (Fig. 4(b)). In contrast, NF-AP60 exhibited the highest SMD value in the warp direction, reflecting a rougher surface texture (Fig. 4(c)).

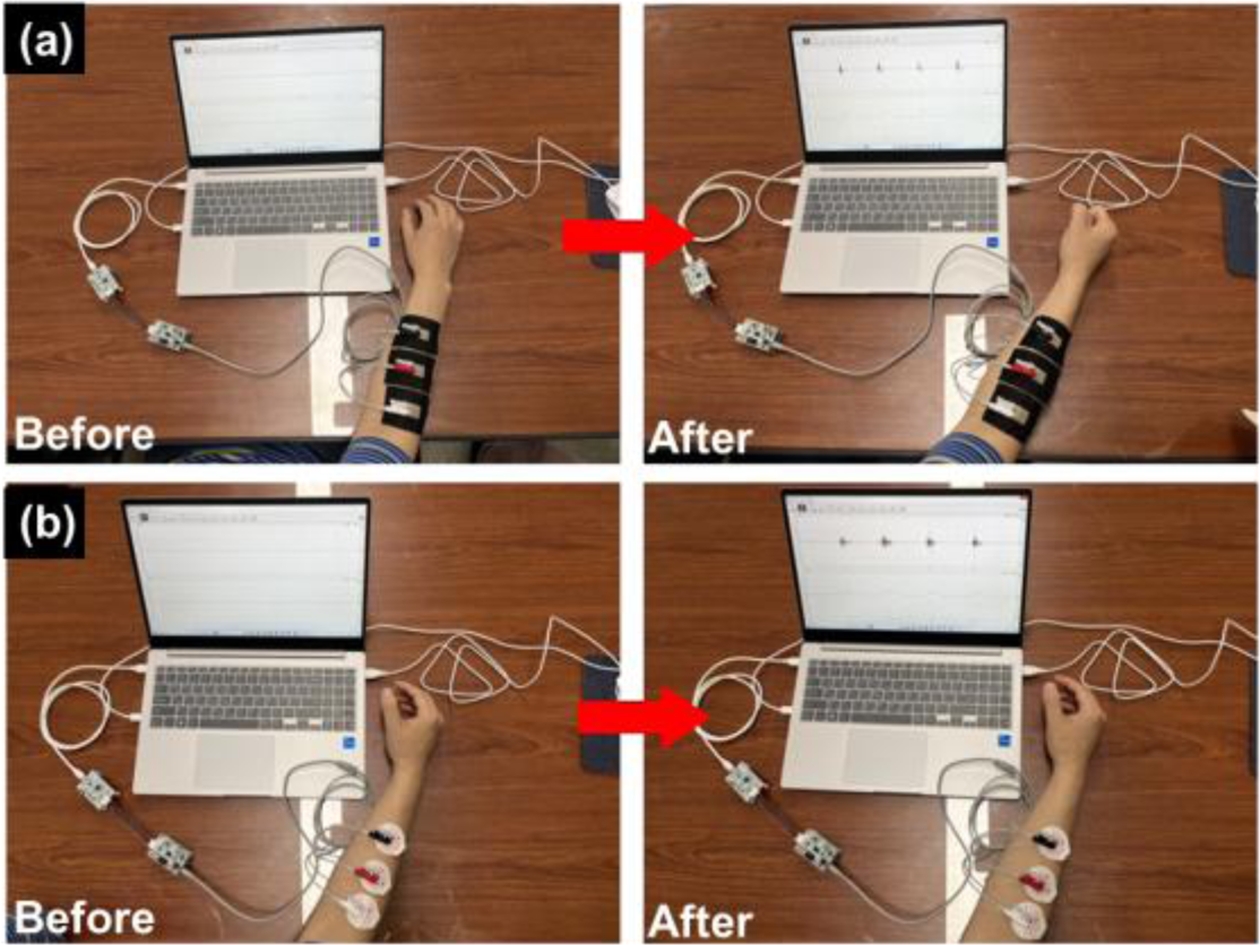

3.3 Performance verification of EMG

A performance evaluation of the textile-based dry electrode for human attachment was conducted by comparing it with the conventional Ag-AgCl wet electrode. The textile-based dry electrode was fabricated in a 5 cm × 5 cm size and equipped with a recessed snap similar to that of the Ag-AgCl wet electrode to ensure smooth connectivity with the EMG module. The testing area was the forearm muscle (forearm flexor), chosen for its large muscle movement and independence from interference. Based on forearm EMG measurement guidelines, the electrode position was adjusted to 1/3 of the distance between the medial acromion and the cubital fossa, with an inter-electrode distance of 20 mm, as shown in Fig. 5. Both the wet and dry electrodes were attached to the positive (+), negative (-), and ground terminals of the EMG module. Since the dry electrode lacks self-adhesive properties, it was secured to the forearm using tape along the edges. To compare muscle activation and relaxation, the experiment involved repetitive forearm muscle contraction and relaxation, with a contraction cycle of 1 second repeated for 5 seconds. Signal data from each experiment were recorded using the PhysioLab PSL-DAQ RMSW software, which is specialized for the EMG module, and the measured RMS data was observed via the serial monitor [9,10].

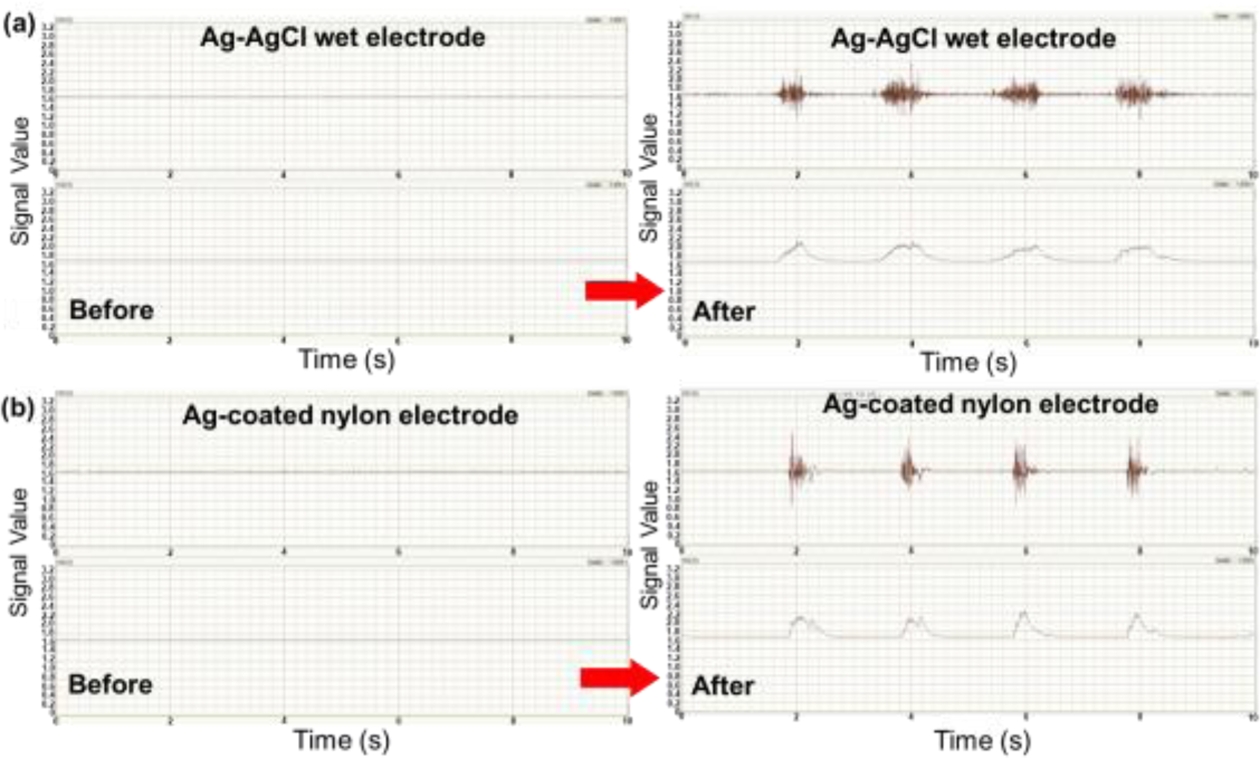

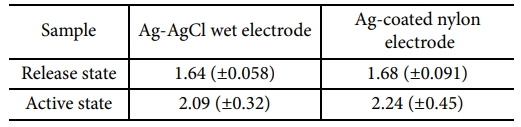

The EMG module used a three-electrode system comprising positive, negative, and ground electrodes. The muscle action potential was collected between the positive and negative electrodes, while the ground electrode served as a reference. It was attached to an area unrelated to the active muscle to enhance the reliability of the data by contrasting the electrical signals gathered from the other two electrodes [9]. Signal data are particularly useful for analyzing muscle activation levels, often utilized to measure and analyze the activation level of specific exercises. The greater the difference between resting and active states, the easier it is to compare muscle activation [4,11]. Raw data are advantageous for noise analysis during muscle activation, and the amplitude of the muscle action potential can be compared to ensure the reliability of the signal data. The dry electrode fabricated with conductive NF-AP30 was connected to a sensor, and four cycles of 1-second biceps rest (release, R) and activation (active, A) exercises were conducted. The mean and standard deviation of the signal values during rest and activation are shown in Table 3.

The analysis of signal data by material in this study aimed to determine whether the data could distinguish between muscle rest and activation states. Therefore, it was necessary to confirm the representative value(mean) and the degree of distribution (standard deviation) of the data for each state. Compared to the wet electrode, the developed Ag-coated nylon electrode showed higher mean signal values and standard deviations during both muscle rest and activation (Fig. 6). Through the analysis of signal and raw data from medical-grade wet electrodes, it was confirmed that the Ag-coated nylon electrode also exhibited low average signal values and standard deviations during muscle rest, demonstrating high stability. These results indicate that the dry electrode provides higher signal intensity and variability than the wet electrode in both states [12].

|

Fig. 3 Tensile stress of Ag-coated nylon electrode |

|

Fig. 4 Tensile stress of Ag-coated nylon electrode |

|

Fig. 5 EMG measurements of forearm muscles; (a) Ag-AgCl wet electrode, (b) Ag-coated nylon electrode (NF-AP30) |

|

Fig. 6 EMG of electrode: (a) muscle relaxation and activation EMG signal from Ag-AgCl wet electrode and (b) Agcoated nylon electrode |

In this study, a dry textile-based electrode suitable for wearable smart devices in the form of clothing was developed, with reliability validation and research on interactions between various factors. To achieve this, conductive fabric was created by coating fabric with silver, a material known for its excellent conductivity. The developed textile-based dry electrodes were then tested for their basic electrical properties, durability against stretching and tearing when applied to the human body, skin feel during wear, resistance changes due to wrinkling and folding during activity, performance changes after washing, and performance. The mechanical strength of the electrode textile made from nylon fabric does not significantly increase with the insertion of Ag powder, but it is speculated that the rate of change in electrical properties can be minimized despite physical damage due to washing durability and repeated deformation. Additionally, it is inferred that the lower the friction coefficient and surface roughness, the higher the performance of the textile electrode, as the area of contact between the conductive fabric and the skin increases. The analysis of muscle activity showed that the signal data during rest/activation and muscle action potentials had similar amplitude values to those of wet electrodes. Through the analysis of signal and raw data from medical-grade wet electrodes, it was confirmed that the Ag-coated nylon electrode also exhibited low average signal values and standard deviations during muscle rest, demonstrating high stability. With low variability and a high SNR, it shows excellent performance as an electrode material. The developed dry textile electrodes demonstrate a significant advance by achieving high signal stability and comfort without the use of conductive gels, highlighting their potential for integration into wearable smart garments. However, certain limitations remain, including the need to optimize coating uniformity and improve adhesion to prevent degradation after repeated washing or extended mechanical deformation. Thus, the present authors believe that this work provides valuable guidance for utilizing the fiber-type dry electrode as a powerful strategy for extending the tuning range in the future design and manufacture of smartwear.

Jong-hyun Joo and Seong-Hwang Kim have contributed equally to this work. This research was supported by the Materials and Components Technology Development Project (RS-2024-00433858, RS-2024-00432340, RS-2024-00428414) co-funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea) and Korea Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology (KEIT, Korea).

- 1. Ning, Q.G., and Chou, T.W., “A Closed-Form Solution of the Transverse Effective Thermal Conductivity of Woven Fabric Composites,” Journal of Composite Materials, Vol. 29, No. 29, 1995, pp. 2280-2294.

-

- 2. Park, Y.B., Yang, H.J., Kweon, J.H., Choi, J.H., and Cho, H.I., “Failure of Composite Sandwich Joints under Pull-out Loading,” Journal of the Korean Society for Composite Materials, Vol. 24, No. 1, 2011, pp. 17-23.

-

- 3. Vinson, J.R., The Behavior of Sandwich Structures of Isotropic and Composite Materials, Technomic Pub. Co., Lancaster, UK, 1999.

-

- 4. Jeong, K.W., Park, Y.B., Choi, J.H., and Kweon, J.H., “A Study on Failure Strength of Composite Key Joint,” Proceeding of the 8th Korea-Japan Joint Symposium on Composite Materials, Changwon, Korea, Nov. 2011, pp. 36-38.

- 5. Cartié, D.D.R., Effect of Z-fibresTM on the Delamination Behaviour of Carbon Fibre/epoxy Laminates, Ph.D Thesis, Cranfield University, UK, 2000.

- 6. Kim, H.L., Rho, S.H., and Lim, D.Y., “Characterization of Embroidered Textile-based Electrode for EMG Smart Wear according to Stitch Technique,” Journal of Fashion and Textiles, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 1-19, 2023.

-

- 7. Kim, H.L., Rho, S.H., and Lim, D.Y., “Fabrication of Textile-Based Dry Electrode and Analysis of Its Surface EMG Signal for Applying Smart Wear,” Journal of Polymers, Vol. 14, No. 17, 3641, 2022.

-

- 8. Kim, S.Y., and Lim, G.Y., “Current Status of International Standardization for Durability Test Methods in Smart Clothing and Future Challenges in Enhancing Product Reliability and Quality Control,” Fashion and Textile Research Journal, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 398-408, 2023.

-

- 9. Finni, T., Hu, M., Kettunen, P., Vilavuo, T., and Cheng, S., “Measurement of EMG Activity with Textile Electrodes Embedded into Clothing,” Journal of Physiological Measurement, Vol. 28, No. 11, pp. 1405-19, 2007.

-

- 10. Kim, S.J., Kim, S.U., and Kim, J.Y., “Resistive E-band Textile Strain Sensor Signal Processing and Analysis Using Programming Noise Filtering Methods,” Journal of Korean Society for Emotion and Sensibility, Vol. 25, pp. 67-78, 2022.

-

- 11. Bauer, G., Pan, Y.J., and Adamson, R., “Analysis of a Low-cost Sensor Towards an Emg-based Robotic Exoskeleton Controller,” Proceedings of the Canadian Society for Mechanical Engineering international Congress, Dalhousie University, Canada, 2018.

-

- 12. Laferriere, P., Lemaire, E.D., and Chan, A.D., “Surface Electromyographic Signals Using Dry Electrodes,” Journal of IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, Vol. 60, pp. 3259-3268, 2011.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 38(6): 657-662

Published on Dec 31, 2025

- 10.7234/composres.2025.38.6.657

- Received on Aug 11, 2025

- Revised on Oct 7, 2025

- Accepted on Nov 18, 2025

Services

Services

- Abstract

1. introduction

2. experimental

3. results and discussion

4. conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Jin-seok Bae ** , Ri-ra Kim ***

-

** Department of Textile System Engineering, Kyungpook National University, Daegu 37224, Korea

*** Corresponding author (E-mail: jbae@knu.ac.kr) Department of Lifestyle Design, Yuhan University, Korea - E-mail: jbae@knu.ac.kr, rira8101@yuhan.ac.kr

Copyright ⓒ The Korean Society for Composite Materials. All rights reserved.

Copyright ⓒ The Korean Society for Composite Materials. All rights reserved.