- Mechanical Properties Improvement of 3D-Printed Aesthetic Dental Artificial Crowns Using UV-Curable Ceramic-Urethane Acrylate Nano-Composite Resins with Varying Filler Ratios

SoonHo Jang**, YuSeong Chae**, YoungHo Cho*, Jinwon Seo*, Dongwook Kim*, MinYoung Shon*†

* Department of Industrial Chemistry and BB 21 plus team, Pukyong National University, Busan 48513, Korea

** R&D Team of Graphy, 79-10, Techno saneop-ro 55beon-gil, Nam-gu, Ulsan 44776, KoreaThis article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This study developed a composite resin by mixing Barium glass, treated with a silane coupling agent, into a photocurable resin composition containing synthesized urethane acrylate oligomers. The chemical structure of the synthesized oligomers was confirmed through FT-IR spectroscopy, and the molecular weight was measured using Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC). The dispersion of barium glass was evaluated using Turbiscan equipment, and the mechanical properties were analyzed using a universal testing machine. Additionally, optimal conditions for 3D printing were established, and the accuracy of the output was assessed through tolerance grading and overlapping 3D image analysis. Furthermore, radiopacity was confirmed by comparing radiographic images with extracted teeth. Experimental results showed that as the content of Barium glass increased, both mechanical strength and dispersion improved, with the highest flexural strength, flexural modulus, and tensile strength observed at 15 wt.%. Moreover, the lowest TSI index was measured under these conditions, confirming the optimal dispersion of Barium glass. The analysis of output accuracy recorded a high precision of over 99.9% while maintaining good dispersion. Radiographic analysis revealed a radiopacity similar to that of dentin compared to actual extracted teeth, and the internal structure was easily observable.

Keywords: Photocurable, Mechanical Properties, 3D-Printing, Nanocomposite, Polyurethane

In endodontic treatment, dental restorative materials such as inlays, artificial teeth, crowns, and bridges are used to replace or restore teeth damaged by caries or fractures. Among these materials, composite resins [1], composed of polymer resins and inorganic fillers, are classified into resin-based, ceramic-based [2,3], and metal-based categories [4]. While metal materials offer excellent mechanical properties, they lack aesthetics and bonding strength with natural teeth, often requiring significant tooth reduction to prevent restoration failure. Ceramic materials possess high strength, transparency, heat resistance, and chemical stability, but their high surface hardness can lead to excessive wear on opposing teeth, and they are prone to brittleness and low resistance to internal defects [5].

Recently, polymer-based photocurable resins used in additive manufacturing technologies, particularly stereolithography (SLA) and digital light processing (DLP), have gained attention in dental prosthetics [6,7]. These technologies allow for the production of precise, customized prosthetics tailored to oral structures, suitable for various dental applications like dental models, temporary crowns, impression trays, orthodontic devices, and surgical guides [8,9]. However, the mechanical properties of polymer materials are typically lower than those of metal and ceramic materials [10].

Photocurable additive manufacturing technologies create customized 3D shapes by selectively exposing a UV light source, layering two-dimensional curing surfaces. Dentist’s design desired tooth positions and occlusion patterns based on oral scan files using CAD software, subsequently stacking two-dimensional sections to form a three-dimensional shape [11].

Radiopacity is a critical property in dental prosthetics, essential for evaluating the fit of restorations, detecting secondary caries, and assessing long-term stability through radiographic imaging. Barium glass, known for its high transparency and radiopacity, is suitable for X-ray analysis and reduces UV light scattering during 3D printing, enhancing mechanical properties [12,13]. Its high elastic modulus, resistance to polymerization shrinkage, and low thermal expansion coefficient minimize deformation, thereby increasing toughness. However, using ceramic particles as fillers in composite materials can lead to reduced dispersion stability between the particles and the polymer due to differences in surface characteristics and density, which may impair mechanical properties [14,15]. Silane coupling agents can modify the surfaces of ceramic particles, enhancing their bonding with organic materials and improving dispersion stability [16].

This study evaluates the dispersion stability, mechanical properties, and radiopacity of composite resins used in 3D printing by adding silane-treated Barium glass as a filler. The research aims to explore the potential of polymer materials containing ceramic fillers for dental prosthetics.

2.1 Materials

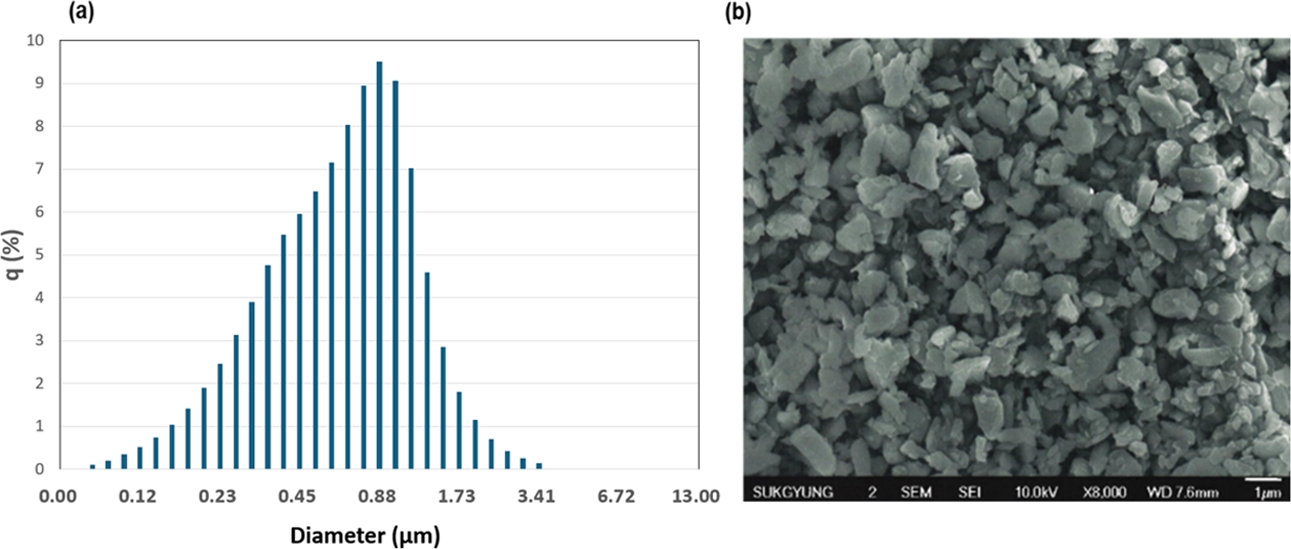

This study utilized Barium glass nanoparticles (Sukgyung AT, Korea), including BaO, α-Al2O3, and amorphous SiO2. The average particle size was 800 nm and the corresponding standard deviation was 0.46 µm. Fig. 1 illustrates the particle size distribution and morphology of the nanomaterials. The particle surfaces were modified with the silane coupling agent 3-(Trimethoxysilyl) propyl methacrylate (CAS No. 2530-85-0), which contains methacryloxy groups (Sigma Aldrich). Additionally, urethane-based oligomers were synthesized in-house.

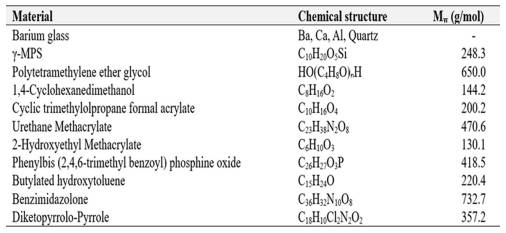

To achieve an A2 shade similar to natural teeth, the synthesized oligomers, monomers, photo initiators, and two types of organic pigments were mixed, with their types, chemical structures, and average molecular weights summarized in Table 1. Barium glass was added to the photocurable resin in varying proportions to create five sample compositions, R100:B0, R95:B5, R90:B10, R85:B15 and R80:B20, which were then used for comparative analysis of mechanical properties.

2.2 Oligomer Synthesis

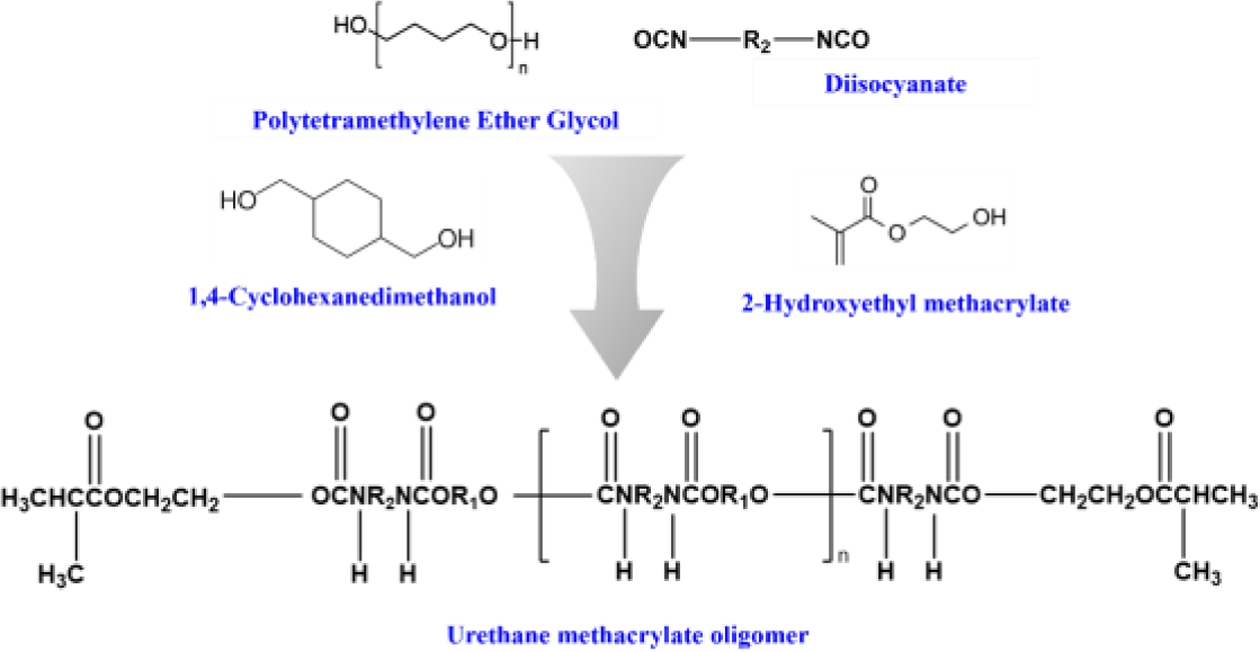

The oligomers used in this study are urethane acrylate oligomers. Urethane linkages are synthesized through the addition polymerization reaction between polyols, isocyanates (-N=C=O), and active hydroxyl groups (-OH), resulting in the release of reaction heat. Bifunctional diols play a crucial role in this process, serving as chain extenders and forming compounds with the [-NHCOO-]n structure, which are referred to as urethane linkages. When n exceeds 1000, the compound is defined as polyurethane.

The combination of urethane and acrylate creates materials with excellent flexibility at low temperatures, along with outstanding optical properties, weather resistance, abrasion resistance, and transparency. This potential, coupled with the ability to design the molecular structure to adjust physical properties, makes these materials a source of inspiration and widely used in adhesives, coatings, and sealants [17]. The synthesis of the urethane oligomer, as depicted in Fig. 2, is a complex process. It is based on Isophorone diisocyanate (Sigma Aldrich) and polytetramethylene ether glycol (Sigma Aldrich), with low molecular weight polyol (1,4-Cyclohexanedimethanol, Sigma Aldrich) and Phenylbis (2,4,6-trimethyl benzoyl) phosphine oxide (Sigma Aldrich) serving as a chain extender. The addition of catalysts and thermal stabilizers to the mixture is crucial, as they induce urethane reactions at 65oC. The introduction of acrylate functional groups to the terminals of the urethane prepolymer through end-capping allows for molecular weight adjustment, adding another layer of complexity to the process.

2.3 Composite Resin Manufacturing

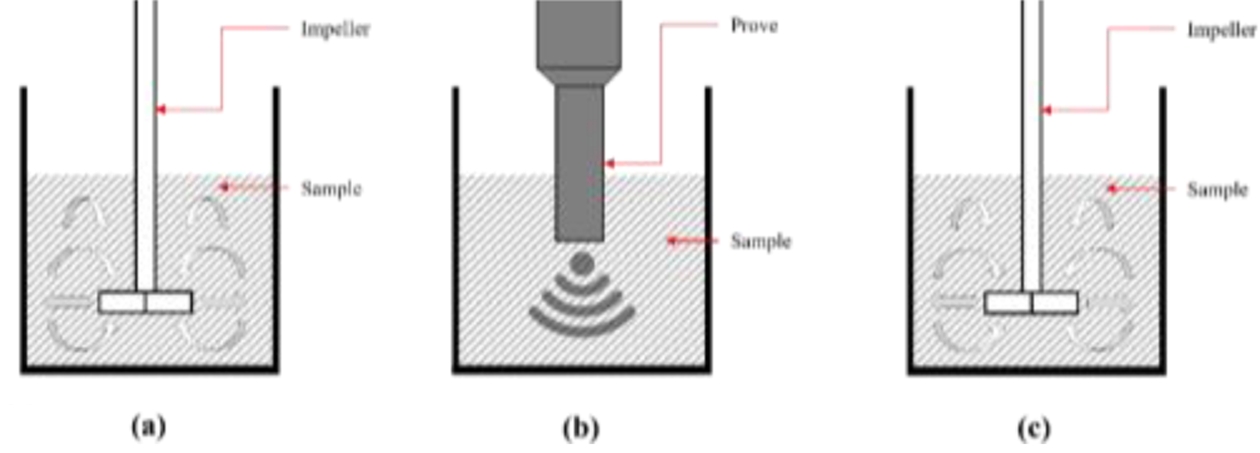

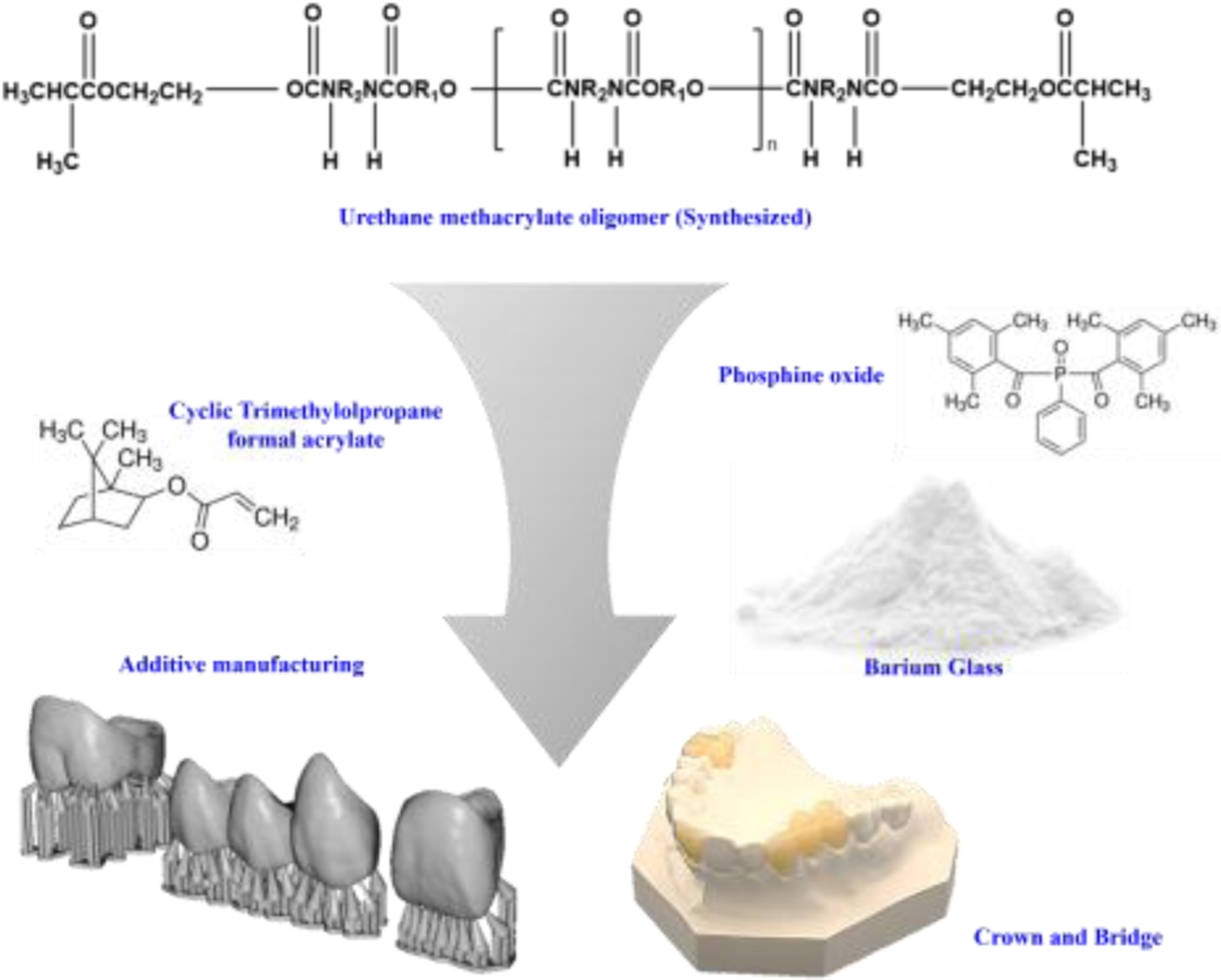

The composite resin was prepared by stirring in a beaker maintained at 60oC using a mixer at 1,500 RPM for 30 minutes. As described in Fig. 3, after the initial mixing, ultrasonic treatment was performed using a probe sonicator for 1 h and 30 min with output power of 64.1 W, following a 6 s pulse and 4-s pause pattern. Once the ultrasonic treatment completed, the composite resin was stirred at room temperature for 3 h to finalize the production. As shown in Fig. 4, the resulting composite resin incorporated surface-modified barium glass in varying ratios of 5 wt.% (R95:B5), 10 wt.% (R90:B10), 15 wt.% (R85:B15), and 20 wt.% (R80:B20), mixed with synthesized oligomers, monomers, and photo initiators. This mixed composite resin was the basis for designing the output shape, which was then produced using 3D printing.

2.4 Characterization

To assess the dispersion effectiveness of the surface-modified particles in the photocurable resin, composite resins mixed in the same ratios were measured and placed in vials at room temperature for an extended period. The dispersion was evaluated by visually inspecting for sedimentation. Additionally, to comprehensively assess the changes in dispersion stability due to sedimentation and agglomeration based on barium glass content, the manufactured composite resin was subdivided and subjected to Turbiscan analysis, measuring the Turbiscan Stability Index (TSI) at 25°C over 5 h at 10-minute intervals [18].

The TSI is defined as the absolute sum of the distance differences between each profile overtime at the sample height. A higher TSI value indicates lower dispersion stability [19].

The composite resin was subjected to 3D layer curing using a UV printer (Slash 2, UNIZ Technology) set to a UV intensity of 8.8 mW/cm². Post-curing was performed in a nitrogen atmosphere for 20 min using a UV curing device (TeraHarz Cure, Graphy Inc) with a UV intensity of 689 mW/cm².

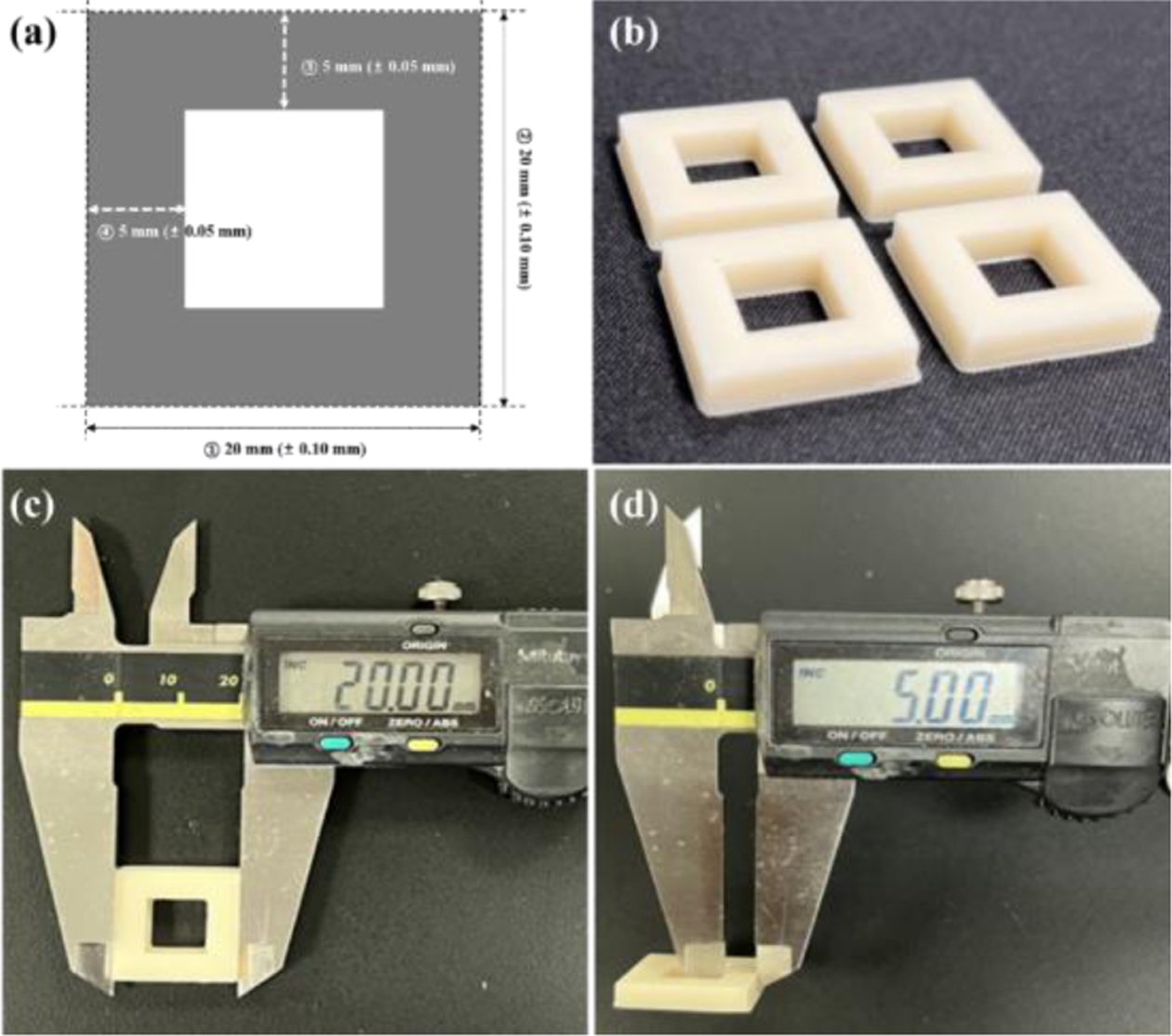

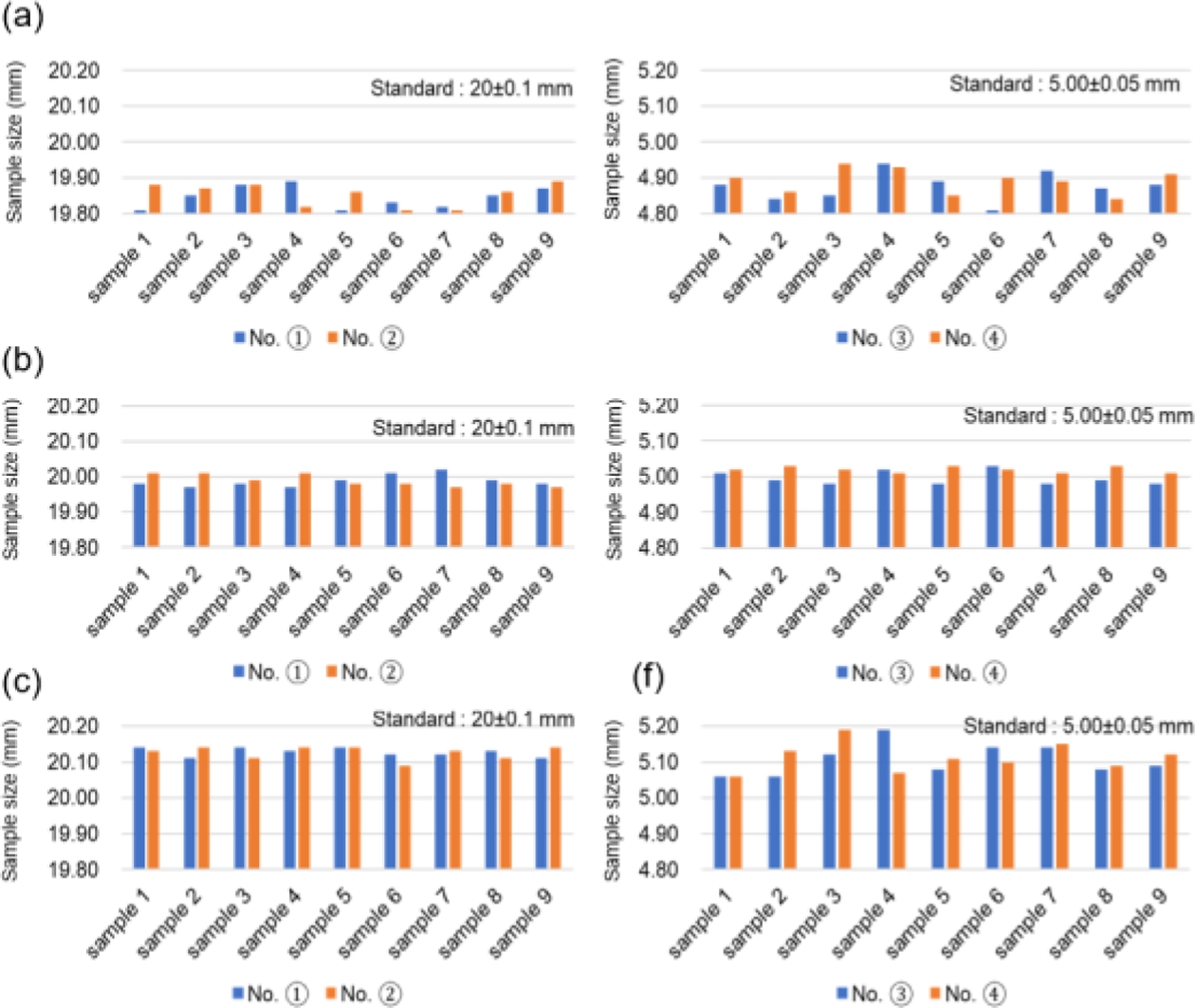

To determine the optimal 3D printing conditions, the UV exposure times were varied at 1.9 s, 2.0 s, and 2.1 s to measure dimensions. Fig. 5(a) shows a rectangular donut specimen designed according to ISO 2768 with an outer length of 20 mm and an inner wall width of 5 mm [20], applying allowable deviations based on each tolerance standard. The specimens cured with the varied exposure times are presented in Fig. 5(b). After the layer curing and post-curing, dimensions were measured at four locations using a Vernier caliper, and the results are shown in Fig. 5(c) and Fig. 5(d).

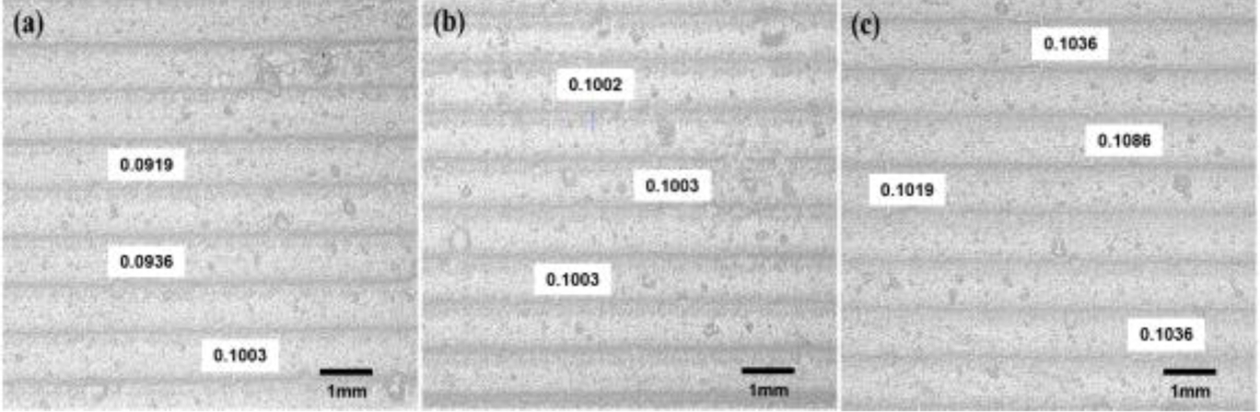

Optical measurements were conducted using a non-contact vision measuring device (EV-2515, Suzhou Easson Optoelectronics Co., Ltd) to verify the actual layer thickness of 100 µm in the printed samples for each UV exposure time. The accuracy of the printed shape was evaluated against the originally designed digital model. The STL file of the original 3D digital model served as the experimental group, while the actual printed shape was scanned using a 3D scanner (E3 Lab scanner, 3Shape) and converted into an STL file for comparison.

The flexural strength specimens were fabricated according to ISO 10477: Polymer-based crown and veneering material, and for the tensile strength specimens (by using a standard dumbbell shape), ASTM D638: Standard test method for tensile properties of plastics were followed. Mechanical property measurements for the printed flexural and tensile specimens were performed using a universal testing machine (ProLine Z010, Zwick/Roell) [21,22].

2.5 Radiopacity Testing

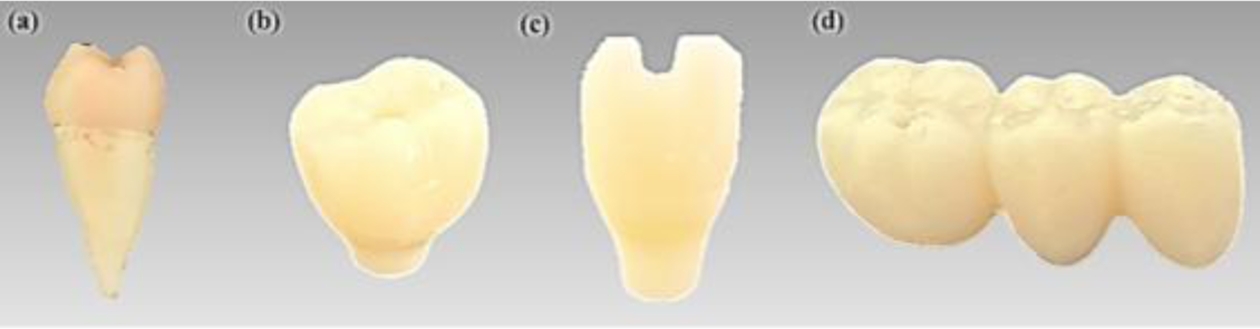

For radiopacity testing, recently extracted teeth were selected as the control group, while three types of crowns and bridges designed via CAD/CAM were 3D printed for the experimental group. Each sample's radiopacity was evaluated by comparing the radiographs. The selected human tooth specimens had low root curvature and a single canal. Prior to testing, the specimens were stored in 2.5% sodium hypochlorite for 24 hs, followed by ultrasonic scaling and root planning to remove residual periodontal tissue and calculus. They were then kept in saline until measurement.

Each specimen was positioned above a digital radiographic sensor and exposed to X-rays using a dental diagnostic X-ray machine (D-65-P/ESX, Vatech Co., Ltd) under the conditions of 65 kV and 5 mA for 0.2 s at a distance of 200 mm below the sensor center, utilizing periapical radiography. The captured radiographs were digitally processed to confirm the internal structure and radiopacity characteristics of the 3D-printed outputs.

|

Fig. 1 (a) Result of laser scattering particle size distribution of silane coated barium glass powder, (b) FE-SEM image of silane coated barium glass powder |

|

Fig. 2 Synthesis process of urethane methacrylate oligomer |

|

Fig. 3 (a) 1st stirring process with 1,500 rpm, 30 min at 60oC (b) Ultrasonication process with 1.5 h by 6s pulse and 4s cooling, (c) 2nd stirring process with 1500 rpm, 3 h at 25oC |

|

Fig. 4 Manufacturing process of composite resin with silane coated Barium glass powder |

|

Fig. 5 General geometric tolerance test (a) test standard on linear length, (b) the specimen preparation, (c) measurement of outline distance (20 mm±0.1 mm), (d) measurement of inner width (5±0.05 mm) |

3.1 Oligomer Synthesis and Dispersion Evaluation of Inorganic-Organic Composite Resin

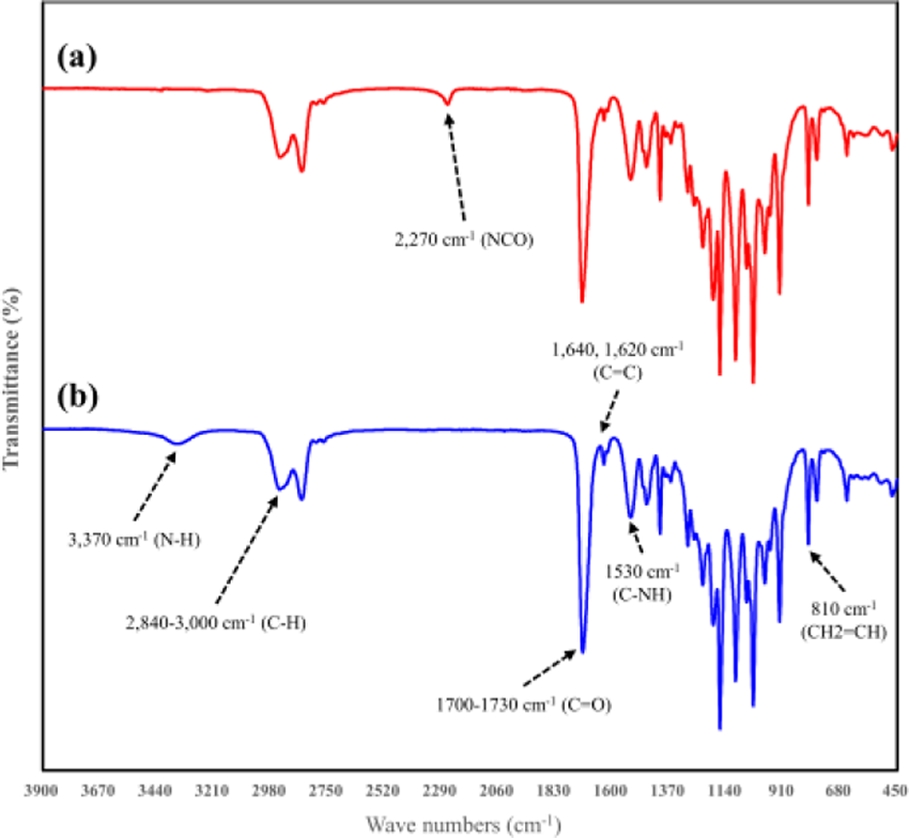

The IR spectrum during the synthesis of photopolymerizable urethane acrylate oligomers is shown in Fig. 7. In panel (a), the spectrum illustrates the formation of a prepolymer with NCO terminal groups, resulting from the reaction between polyol and isocyanate. The characteristic peak of isocyanate (NCO) appears at 2,270 cm-1 [23], while the C-H stretching vibration peaks are observed in the range of 2,840–3,000 cm-1.

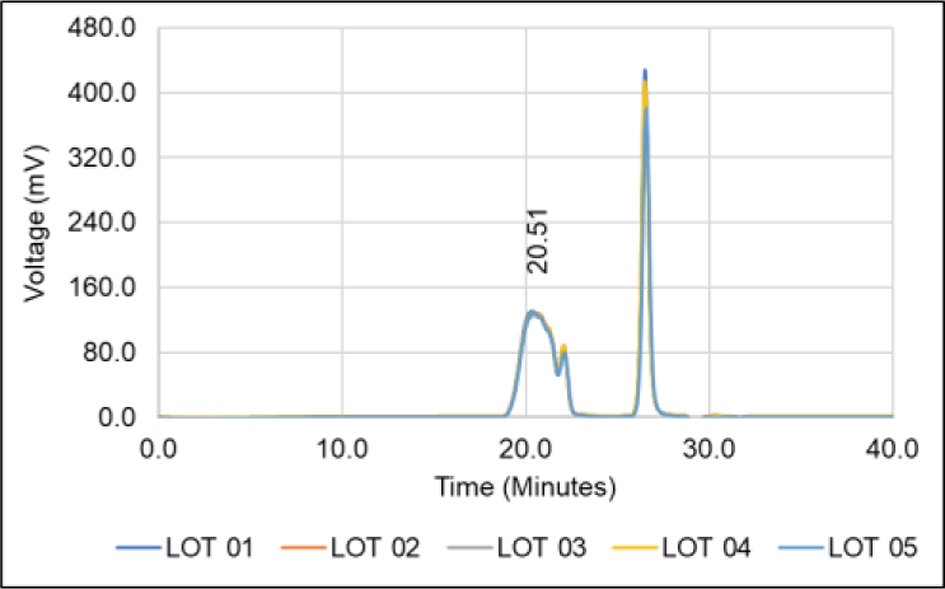

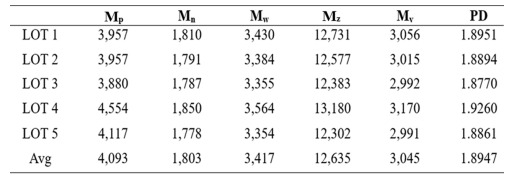

In panel (b), the spectrum of the completed oligomer is presented. Here, the NCO characteristic peak at 2,270 cm-1 disappears, and a peak corresponding to the N-H bond, indicative of urethane linkages, appears at 3,370 cm-1 [24], confirming the completion of the synthesis. The results of Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) analysis of the synthesized oligomer are illustrated in Fig. 8, revealing an average molecular weight (Mw) of 3,417 g/mol. The detailed measurement results are summarized in Table 2.

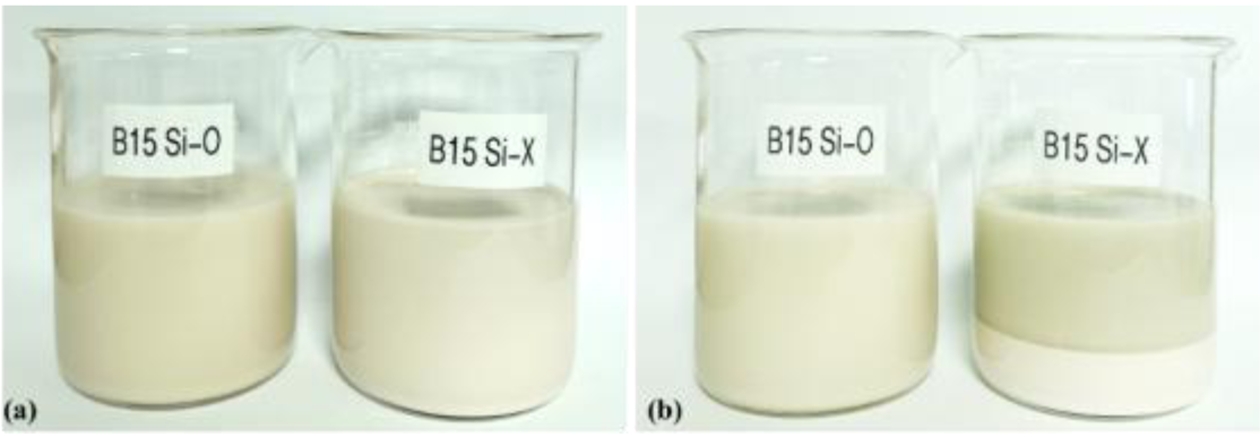

To visually evaluate the dispersion effectiveness of the composite resin manufactured using silane-coupling-agent-treated powders, a mixture was prepared with 15 % of both treated and untreated powders, as illustrated in Fig. 9(a).

After 24 h of standing, the sedimentation was assessed. The results shown in Fig. 9(b) demonstrate that the resin containing the silane-coupling-agent-treated powders exhibited no particle sedimentation, maintaining good dispersion. In contrast, the resin with untreated powders failed to maintain dispersion, resulting in particle sedimentation at the bottom of the beaker.

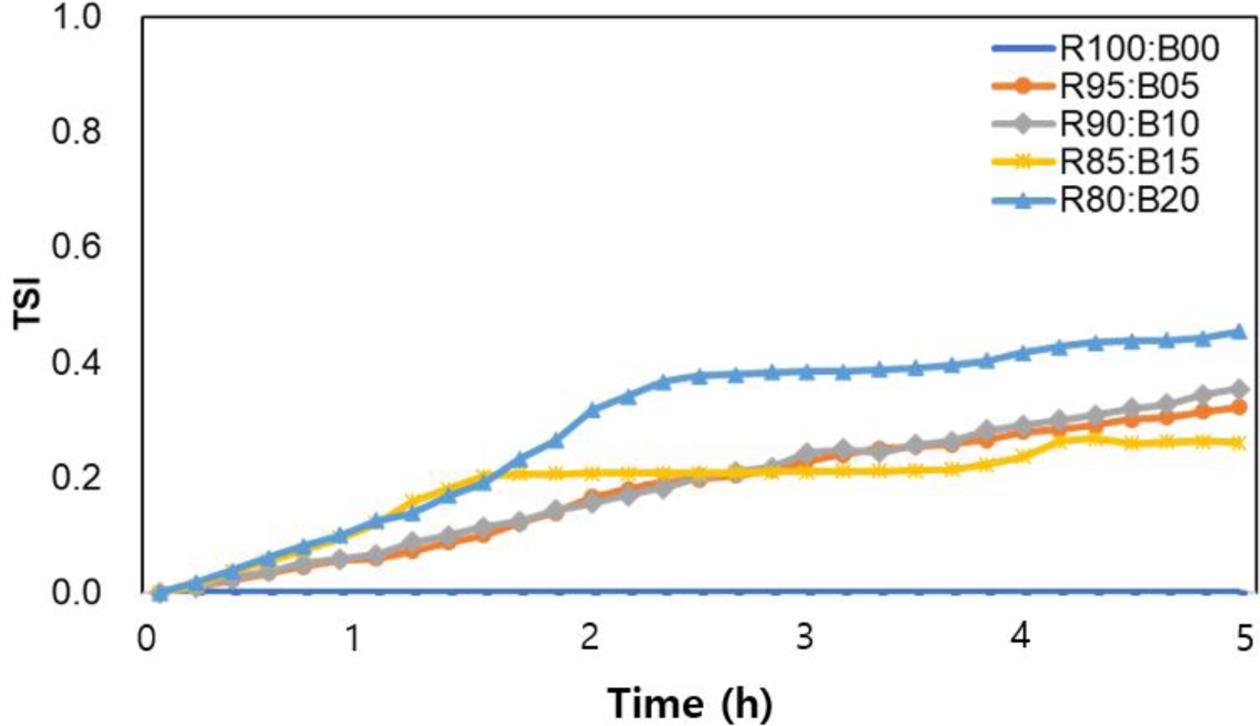

Based on this, the changes in dispersion stability corresponding to varying contents of surface-modified Barium glass were analyzed using the Turbiscan Stability Index (TSI), as shown in Fig. 10 [25]. The results indicate that the R85:B15 composition exhibited the best dispersion stability during the 5-h experiment. In compositions with 5-10% modified Barium glass, the TSI index increased over time; however, initially, it remained lower than the 15% composition, suggesting that dispersion was maintained. Notably, after 3 h, the TSI index for these compositions surpassed that of the 15% composition. In contrast, when the particle ratio increased to 20%, the TSI index experienced the most significant rise, indicating substantial changes in the sample due to reduced dispersion stability. Ultimately, these findings demonstrate that the surface-modified Barium glass powder can maintain good dispersion stability at levels up to 15%.

3.2 Evaluation of Optimal Output Conditions

To establish the output conditions for the composite resin containing surface-modified Barium glass powder, the UV exposure time at 405 nm was varied while printing standard square donut specimens. The dimensions of each test specimen were measured to ensure compliance with the specified tolerance grades, as shown in Fig. 11.

In panel (a), when the exposure time was adjusted to 1.9 s, it was visually confirmed that the specimen adhered to the platform without detaching during the layer curing process. However, the measurements indicated that the size of the cured specimen did not meet the tolerance criteria, resulting in a dimension smaller than the intended size. Panel (b) reflects the results when the exposure time was increased to 2.0 s, demonstrating that both the shape dimensions and tolerance criteria were satisfied. Conversely, in panel (c), increasing the exposure time to 2.1 s led to excessive curing, resulting in a specimen larger than the specified dimensions. Additionally, the layer height was uniformly set to 100 µm under each UV exposure condition, and the measured layer thicknesses are presented in Fig. 12. In panel (a), with a 1.9-second UV exposure, an average layer thickness of 95.2 µm was measured, indicating insufficient exposure time to achieve the full 100 µm layer height. In panel (b), with an exposure of 2.0 s, an average thickness of 100.2 µm was achieved, confirming that the applied layer height during slicing was adequately satisfied. However, in panel (c), with a 2.1-s exposure, the measured thickness averaged 105.4 µm, indicating over-curing. The over-cured layer thickness resulted in subsequent layers being cured at a greater height than intended, potentially leading to a decline in the precision of the final shape.

3.3 Analysis of Mechanical Properties

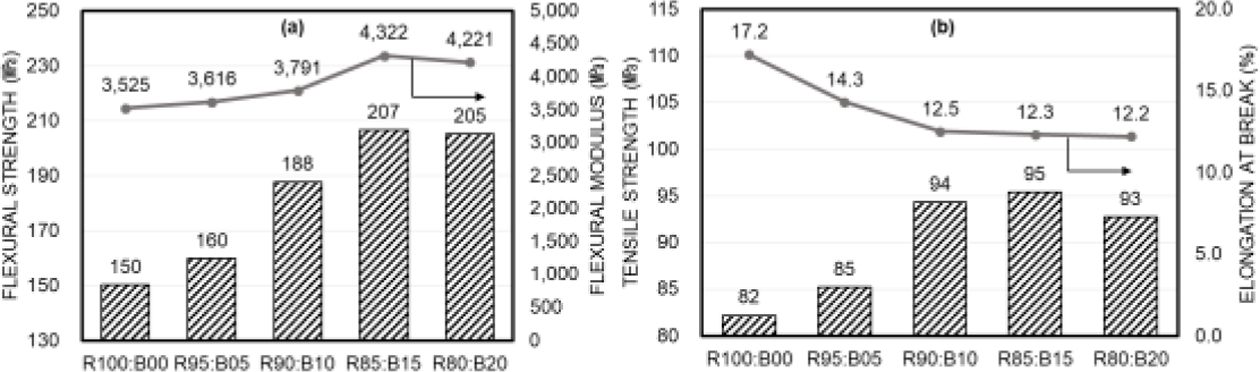

Fig. 13 compares the composite resin's flexural strength and tensile strength from five experimental groups. Panel (a) presents the results of flexural strength and flexural modulus measurements, showing the highest values for the R85:B15 composition. The R95:B5 formulation did not exhibit a significant increase in strength compared to the powder-free R100:B0 composition, while a notable trend of increased strength was observed in the R90:B10 formulation. In the R80:B20 composition, no significant increase in strength was detected compared to the R85:B15 formulation and similar trends were noted for the flexural modulus.

The results of tensile strength and elongation measurements are shown in panel (b). The tensile strength did not show significant increases in the R100:B0 and R95:B5 compositions, but strength improvements were confirmed in formulations with R90:B10 or higher ratios. Additionally, the tensile strength measurement for the R80:B20 composition showed a slight decrease compared to the R85:B15 formulation. In contrast, the elongation decreased with increasing Barium glass powder content, gradually declining at compositions of 10 wt.% or more.

This phenomenon suggests that the surface-modified Barium glass particles act as insoluble, non-reactive materials dispersed within the polymer matrix, effectively enhancing mechanical properties. However, when the content of insoluble non-reactive materials exceeds a certain threshold, it may negatively affect the radical polymerization process involved in the photo-curing of the resin structure, leading to a reduction in strength due to unfavorable effects on the formation of the crosslinked network of the photopolymer.

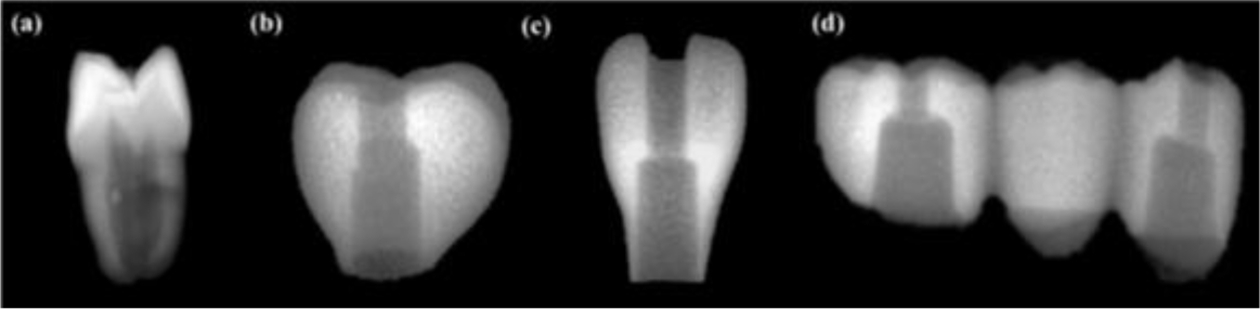

3.4 Radiopacity

Fig. 14 illustrates the radiopacity characteristics of three types of artificial crowns fabricated through layer-by-layer curing with the R85:B15 composition, compared to actual extracted teeth captured via radiographic imaging. The radiopacity of the 3D-printed artificial teeth was found to be higher at dentin but that of lower at enamel, when compared to the actual extracted teeth. Overall, the high dispersion of inorganic particles within the printed materials resulted in a clear delineation of the shapes in the radiographic images, and the shape of the inner hole, designed for the connection with the upper structure, was also visible in the photographs.

|

Fig. 6 (a) Extracted natural crown, (b) 3D printed artificial second molar crown, (c) 3D printed artificial lateral incisor crown, (d) 3D printed 3-unit bridge |

|

Fig. 7 FT-IR spectra of (a) prepolymer of urethane acrylate oligomer (b) Synthesized urethane acrylate oligomer |

|

Fig. 8 GPC result of synthesized Urethane acrylate oligomer |

|

Fig. 9 (a) Mixed composite resin with 15 wt.% barium glass between silane coated powder and raw powder, (b) Result of 24 h after with 15 wt.% barium glass between silane coated powder and raw powder |

|

Fig. 10 TSI curves of composite resin with different barium glass composite ratio in terms of time |

|

Fig. 11 General geometric tolerance test of (a) 1.9 s of UV exposure time, (b) 2.0 s of UV exposure time, (c) 2.1 s of UV exposure time |

|

Fig. 12 Layer thickness measurement which designed by 100um when (a) 1.9 s of UV exposure time, (b) 2.0 s of UV exposure, (c) 2.1 s of UV exposure |

|

Fig. 13 (a) Flexural strength and flexural modulus results of 3D printed object with different R/B particle ratio. (b) tensile strength and elongation at break result of 3D printed object with different particle ratio |

|

Fig. 14 Radiography of (a) Extracted natural crown, (b) 3D printed artificial second molar crown, (c) 3D printed artificial lateral incisor crown, (d) 3D printed 3-unit bridge |

In this study, we enhanced the strength of inorganic-organic composite resins used in digital light processing technology by modifying the surface of Barium glass particles through hydrolysis and condensation reactions with a silane coupling agent. The surface-modified powder was dispersed in a photocurable composite resin formulation using self-synthesized oligomers. The R85:B15 composition exhibited the lowest Turbiscan Stability Index (TSI), indicating the highest dispersion stability.

As the Barium glass content increased, there was a tendency for flexural strength, flexural modulus, and tensile strength to rise, while elongation at break decreased with increasing Barium glass content. However, above 10 wt.%, the elongation reduction was insignificant and remained relatively constant. In contrast, compositions exceeding 20 wt.% exhibited a decline in flexural strength, flexural modulus, and tensile strength. Therefore, it was clearly suggested that an excess of insoluble, non-reactive materials interferes with the radical polymerization process during photopolymerization, acting as a detrimental factor that negatively impacts the mechanical properties.

This work was financially funded by a Research Grant of Pukyong National University (2025).

- 1. Cramer, N., Stansbury, J., and Bowman, C., “Recent Advances and Development in Composite Dental Restorative Materials,” Journal of Dental Research, Vol. 90, 2011, pp. 402–416.

-

- 2. Denry, I., and Holloway, J., “Ceramics for Dental Applications: A Review,” Materials, Vol. 3, 2010, pp. 351–368.

-

- 3. Auschill, T., Arweiler, N., Brecx, M., Reich, E., Sculean, A., and Netuschil, L., “The Effect of Dental Restorative Materials on Dental Biofilm,” European Journal of Oral Sciences, Vol. 111, 2002, pp. 48–53.

-

- 4. Huang, B., Chen, M., Wang, J., and Zhang, X., “Advances in Zirconia-Based Dental Materials: Properties, Classification, Applications and Future Prospects,” Journal of Dentistry, Vol. 147, 2024, Article ID 105111.

-

- 5. Shiv, H., Pang, R., Yang, J., Fan, D., Cai, H., Jiang, H., and Han, J., “Overview of Several Typical Ceramic Materials for Restorative Dentistry,” BioMed Research International, 2022, Article ID 8451445.

-

- 6. Zakeri, S., Vippola, M., and Levänen, E., “A Comprehensive Review of the Photopolymerization of Ceramic Resins Used in Stereolithography,” Additive Manufacturing, Vol. 35, 2020, pp. 101–177.

-

- 7. Song, S., Park, M., and Yun, J., “Dispersion Stability and Mechanical Properties of ZrO₂–CNF/Photopolymer Composite Resins by Carbon Nanofiber Contents for SLA 3D Printing,” Journal of the Korean Society of Manufacturing Technology Engineers, Vol. 27, 2018, pp. 140–145.

-

- 8. Simeon, P., Unkovskiy, A., Sarmadi, B., Nicic, R., Koch, P., Beuer, F., and Schmidt, F., “Wear Resistance and Flexural Properties of Low Force SLA- and DLP-Printed Splint Materials in Different Printing Orientations: An In Vitro Study,” Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials, Vol. 152, 2024, Article ID 106458.

-

- 9. Song, S., Park, M., and Yun, J., “Dispersion Stability and Mechanical Properties of ZrO₂/High-Temp Composite Resins by Nano- and Micro-Particle Ratio for Stereolithography 3D Printing,” Korean Journal of Materials Research, Vol. 29, 2019, pp. 221–227.

-

- 10. Pratap, B., Gupta, R., Bhardwaj, B., and Nag, M., “Resin-Based Restorative Dental Materials: Characteristics and Future Perspectives,” Japanese Dental Science Review, Vol. 55, 2019, pp. 126–138.

-

- 11. Liu, C., Li, D., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Ning, S., Zhao, G., Ye, Z., Kond, Y., and Yang, D., “Prospects for 3D Printing of Clear Aligners—A Narrative Review,” Frontiers in Materials, Vol. 11, 2024, Article ID 1438660.

-

- 12. Won, S., Ko, K., Park, C., Cho, L., and Huh, Y., “Effect of Barium Silicate Filler Content on Mechanical Properties of Resin Nanoceramics for Additive Manufacturing,” The Journal of Advanced Prosthodontics, Vol. 14, 2022, pp. 315–323.

-

- 13. Bowen, R., and Cleek, G., “A New Series of X-ray Opaque Reinforcing Fillers for Composite Materials,” Journal of Dental Research, Vol. 51, 1972, pp. 177–182.

-

- 14. Lopez, C., Nizami, B., Robles, A., Gummadi, S., and Lawson, N., “Correlation between Dental Composite Filler Percentage and Strength, Modulus, Shrinkage Stress, Translucency, Depth of Cure and Radiopacity,” Materials, Vol. 17, 2024, Article ID 3901.

-

- 15. Ferracane, J., “Current Trends in Dental Composite,” Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine, Vol. 6, 1995, pp. 302–318.

-

- 16. Chao, X., Yi, W., Ming, H., Ying, H., and Wei, G., “Study on the Structure and Mechanical Properties of Dental Barium Glass Particles Surface Modification with Silane Coupling Reagent,” Polymer-Plastics Technology and Engineering, Vol. 47, 2008, pp. 858–864.

-

- 17. Kim, S., Baek, L., Koo, B., Choi, J., Cheon, J., and Chun, J., “Synthesis and Properties of Photo-Curable Biomass-Based Urethane Acrylate Oligomers,” Journal of Adhesion and Interface, Vol. 24, 2023, pp. 26–35.

-

- 18. ISO/TR 13097:2013, Guidelines for the Characterization of Dispersion Stability.

- 19. Kim, H., Han, K., Hwang, K., Nahm, S., and Kim, J., “Printability of Thermally and Chemically Stable Silica–Titanium Dioxide Composite Coating Layer,” Korean Journal of Materials Research, Vol. 29, 2019, pp. 631–638.

-

- 20. ISO 2768-1:1989, General Tolerances—Part 1: Tolerances for Linear and Angular Dimensions without Individual Tolerance Indications.

- 21. ISO 10477:2004, Dentistry—Polymer-Based Crown and Veneering Materials.

- 22. ASTM, “ASTM D638 – Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics.”

-

- 23. Kunwong, D., Sumanochitraporn, N., and Kaewpirom, S., “Curing Behavior of a UV-Curable Coating-Based Urethane Acrylate Oligomer: The Influence of Reactive Monomers,” Songklanakarin Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 33, 2011, pp. 201–207.

- 24. Opera, S., Vlad, S., and Stanciu, A., “Poly(urethane-methacrylate)s: Synthesis and Characterization,” Polymer, Vol. 42, 2001, pp. 7257–7266.

-

- 25. Yang, H., Kang, W., Yu, Y., Yin, X., Wang, P., and Zhang, X., “A New Approach to Evaluate the Particle Growth and Sedimentation of Dispersed Polymer Profile Control System Based on Multiple Light Scattering,” Powder Technology, Vol. 315, 2017, pp. 477–485.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 38(6): 670-676

Published on Dec 31, 2025

- 10.7234/composres.2025.38.6.670

- Received on Oct 31, 2025

- Revised on Nov 11, 2025

- Accepted on Nov 27, 2025

Services

Services

- Abstract

1. introduction

2. experimental

3. results and discussion

4. conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- MinYoung Shon

-

Department of Industrial Chemistry and BB 21 plus team, Pukyong National University, Busan 48513, Korea

- E-mail: myshon@pknu.ac.kr

Copyright ⓒ The Korean Society for Composite Materials. All rights reserved.

Copyright ⓒ The Korean Society for Composite Materials. All rights reserved.