- Numerical Design of Ceramic Particle–containing Heat Dissipation Polymer Coatings for Agricultural Applications

Hye Seong Seo*, Yun Sik Park*, Jung Hyuk Jang*, Yi Je Cho*†

* Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Sunchon National University, Suncheon 57922, Korea

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

A rapid decrease in the temperature of the CO2-adsorbing medium at desired moments to desorb gas is necessary for agricultural applications, for which a ceramic particle–containing polymer coating can improve heat dissipation efficiency. In this study, ceramic particle–containing polymer coatings were numerically designed for agricultural applications. The mechanical and thermal properties of polymer coatings with 40–50 vol%Al2O3 or SiC particles were predicted using a microscale model. Young’s modulus and thermal conductivity increased with the particle content, while thermal expansion and specific heat capacity decreased. The increases in these properties were greater for coatings with SiC than for those with Al2O3. The estimated properties were utilized to simulate the heat transfer and thermal shock behavior of the coating using a macroscale model. The heat dissipation performance was enhanced by the coatings compared to the bare metal, and the stress difference at the interface between the coating and substrate varied with coating thickness and type of ceramic particle. The numerical results were validated through experimental measurements. The coatings with highly connected particles and no defects showed high thermal conductivity.

Keywords: Polymer coating, Ceramic particle, Heat dissipation, Numerical design

Carbon capture and utilization (CCU) has received great attention for using captured CO2 as a renewable carbon feedstock to produce valuable products instead of permanently sequestering the gas [1]. The biological conversion route consists of utilizing CO2 in the production of various biomass-based products such as fertilizers, food, fodder, and biogas. CO2 is used to increase crop production and growth by enhancing photosynthesis [2]. In addition, this route reduces land competition by enhancing crop yields, enables quicker crop production cycles, and improves waste recycling and utilization [1]. Highly porous media, such as carbon-based materials, are promising candidates for adsorbing CO2 owing to their high specific surface area, low cost, excellent chemical stability, hydrophobicity, controllable textural properties, and low energy requirements for regeneration [3,4]. In order to properly adsorb and desorb CO2 for agricultural applications at desired moments, a rapid change in the temperature of the adsorbing medium is important. Since the adsorbing media are embedded in metallic columns or cells, enhancing heat dissipation from the metallic surfaces to the surrounding atmosphere is a promising solution to shorten the CO2 adsorption–desorption cycle duration.

Ceramic particle–containing polymer coatings have been utilized for thermal management owing to their easy processing, low cost, high thermal conductivity, and high atmospheric emissivity in the mid-infrared region [5-7]. Various ceramic particles, including Al2O3 [8,9], SiC [10], TiO2 [11], SiO2 [12], have been widely investigated. These ceramic particles possess thermal conductivities on the order of ~490 W/m·K, whereas typical polymers have low conductivities of ~0.5 W/m·K [13]. Their emissivity in the mid-infrared region has been reported to be in the range of 0.8–0.9 [6], which is significantly higher than that of metallic radiator surfaces (0.1–0.2) [14,15]. The formation of conductive pathways is an important factor for increasing thermal conductivity [13], and is influenced by the content, size, shape, and spatial distribution of the particles [9,16]. In addition, emissivity depends on the inherent lattice absorption of polar bonds and the roughness and micropores of the coating surface [17,18]. Since both inherent material properties and microstructural factors influence thermal conductivity and emissivity, proper selection of component materials and optimization of microstructures are necessary to maximize heat dissipation efficiency. Microstructure modeling using the finite element method is an effective tool for designing composite materials and can be used to estimate effective properties for various microstructures [19,20].

In this study, ceramic particle–containing polymer coatings were numerically designed, and their mechanical and thermal properties were estimated to improve heat dissipation efficiency. Finite element analysis was conducted using microscale representative volume element (RVE) models to predict the properties of the designed microstructures, and the resulting properties were used to estimate the heat transfer and thermal shock behavior of the coatings in macroscale column models. The microstructures and thermal conductivity of stainless steel plates with coatings were then experimentally examined to validate the numerical results.

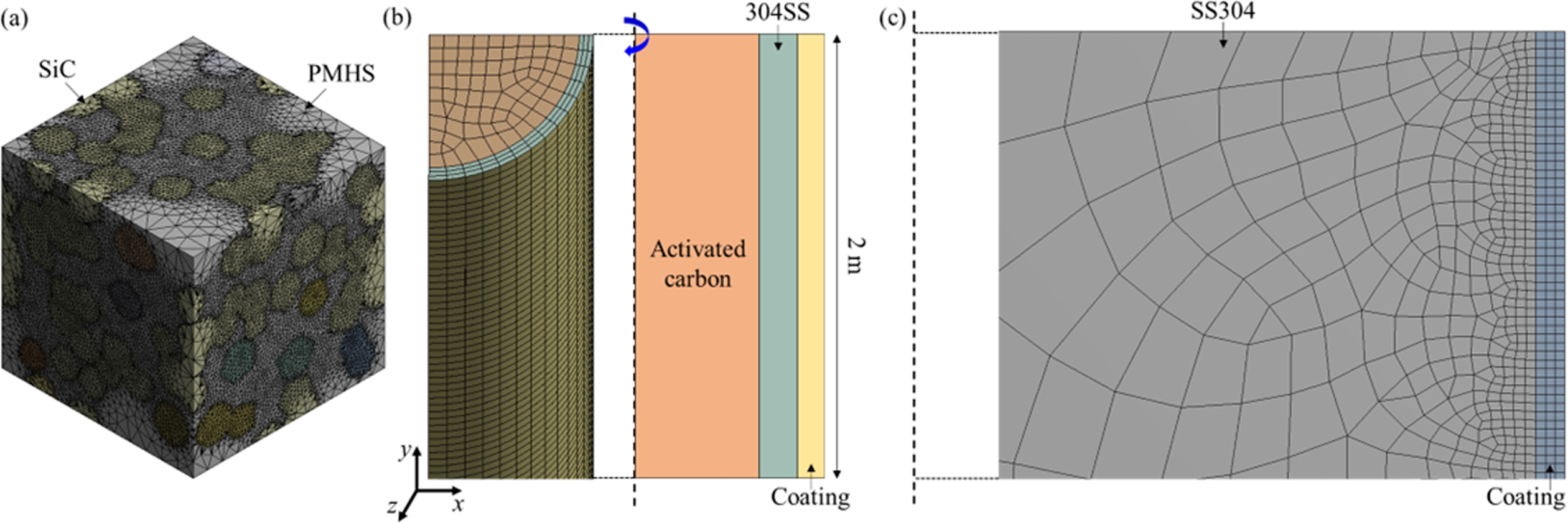

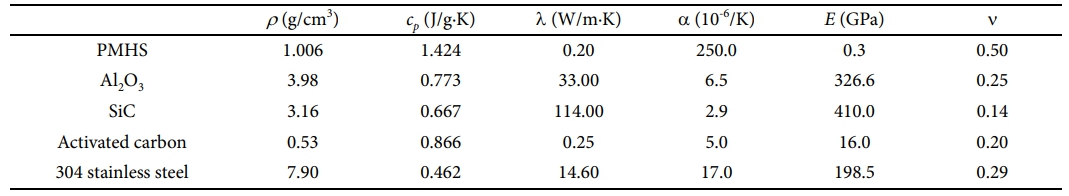

Poly(methyl)hydrosilane (PMHS) coatings were chosen for the study, with Al2O3 (average diameter = 2.1 μm, purity = 99%) and SiC (average diameter = 26.7 μm, purity = 98%) particles considered as additives. For microscale modeling, cubic 3D RVE models with randomly distributed ceramic particles were generated using a random algorithm. The particles had a 20-faced polyhedral shape, and their volume fractions were 40 and 50%, respectively. Particle overlapping was allowed to alleviate the limitations of the random algorithm when generating RVEs with high volume fractions of particles, while constraining the overlap to within 10% of each particle volume to preserve microstructural realism. The edge lengths of the RVE models were 10.5 and 133.5 mm for coatings with Al2O3 and SiC particles, respectively. A typical RVE geometry is shown in Fig. 1a. The RVE model was subjected to a 0.1% tensile strain to estimate the elastic properties, including Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio, using appropriate boundary conditions [20]. To predict thermal conductivity, a heat flux of 1 W/m2 was applied to one outer surface of the RVE, while the temperature on the opposite surface was measured and the remaining surfaces were insulated. The specific heat capacity was estimated by applying a volumetric heat generation rate of 1 W/m3 under adiabatic boundary conditions. The axial displacements were measured to predict the coefficient of thermal expansion by increasing the model temperature to 100 °C. The material properties used for the analysis are listed in Table 1. All materials were assumed to be isotropic and linearly elastic. The PMHS coatings with 40 and 50 vol%Al2O3 or SiC are referred to as P6A4 and P5A5, and P6S4 and P5S5, respectively. The wavelength-dependent complex refractive indices of PMHS, Al2O3, and SiC were collected to estimate the coating emissivity [21-23]. The effective complex permittivity of the PMHS coating with Al2O3 was computed through the Bruggeman effective medium approximation [24], and then used to calculate the effective complex refractive index. The coating was assumed to be a homogeneous layer in contact with air, and transmission in the infrared was neglected. Under this condition, the total hemispherical emissivity was obtained by Planck-weighted spectral averaging over the thermal infrared band. Since the SiC particles considered in this study were larger than the dominant thermal radiation wavelengths, a particle-resolved radiative transfer approach combining Mie scattering theory and a d-Eddington two-stream model was used [25], which yielded the relationship between coating thickness and total hemispherical emissivity.

The estimated properties of the coatings were used as inputs for analysis with the macroscale column model. The effects of the coatings on the cooling efficiency of the columns and on the thermal stress at the interface between the column surface and the coated materials were investigated. Heat transfer analysis was performed to predict the time required to cool the column surface to 30 °C. A column with a length of 2 m was filled with a CO2-absorbing medium (activated carbon) and covered by ceramic particle–containing coatings (Fig. 1b). A quarter of the column was modeled using cyclic symmetry. The absorbing medium and stainless steel were 12.7 and 1.2 mm thick along the x-axis, respectively. The coating thickness varied from 10 to 100 mm. The whole model, with an initial temperature of 75 °C, was cooled by convection and radiation through the coating surface. The convection coefficient of still air was 5 W/mm2. The top and bottom surfaces of the model were insulated. For thermal stress analysis, the temperature distributions as a function of time obtained from the heat transfer analysis were used as boundary conditions. A 2D axisymmetric model was built, as the stress evolution at the interface between the column and coating was of primary interest (Fig. 1c). The dimension of the column cross section was 12 × 12 mm2. The thermal stress that evolved after one cycle of heating and cooling was estimated.

To validate the numerical results, Al2O3 (Duksan Regents, South Korea) or SiC (Daejung Chemical & Metals, South Korea) particle–containing PMHS (Sigma Aldrich, USA) coatings were fabricated on 304 stainless-steel plates (304SS, Iwata Mfg., Japan) with a thickness of 1.2 mm. The coating solutions were prepared by mixing PMHS and ceramic particles in volumetric ratios of 6:4 and 5:5. Spray coating was carried out by applying the mixed solutions to the stainless-steel plates at a pressure of 5 kPa, with a spray distance of 0.5 m from the spray gun. The samples were cured at 150 °C for 12 h. The cross sections and thermal conductivities of the samples were analyzed.

|

Fig. 1 A geometry of (a) typical microscale RVE model with ceramic particles and (b) macroscale heat transfer and (c) thermal stress models. |

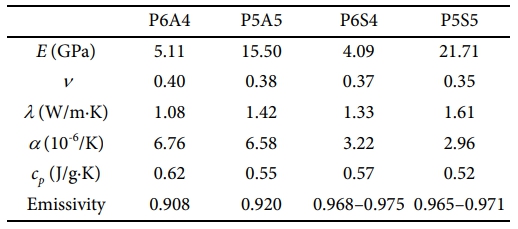

The typical deformed geometries of the RVE models subjected to tensile deformation (Fig. 2a) and thermal expansion (Fig. 2b) are presented in Fig. 2. The mechanical and thermal properties predicted by the numerical analysis are summarized in Table 2. Young’s modulus increases with increasing ceramic particle content, with P5S5 exhibiting the highest modulus. Poisson’s ratios of the coatings are lower than that of PMHS, indicating increased resistance to lateral deformation. The thermal conductivity improves significantly with the addition of ceramic particles and is at least five times higher than that of pure PMHS. The thermal expansion of the coatings is suppressed by the ceramic particles, which is beneficial for preventing detachment of the coating from the substrate. The emissivity of the coatings with SiC is higher than that of the coatings with Al2O3.

Heat transfer is classified into conduction, convection, and radiation, which occur simultaneously in the same system. If convective heat transfer by air at a material surface is constant, the cooling rate is dominated by conduction and radiation, which are governed by the thermal properties of the materials.

A material with high thermal conductivity and emissivity and low specific heat capacity will cool the surface of the 304SS column more rapidly. In addition, a small difference in mechanical properties between 304SS and the coating reduces the likelihood of coating debonding. Based on the obtained properties, coatings with SiC seemed appropriate for improving heat dissipation efficiency.

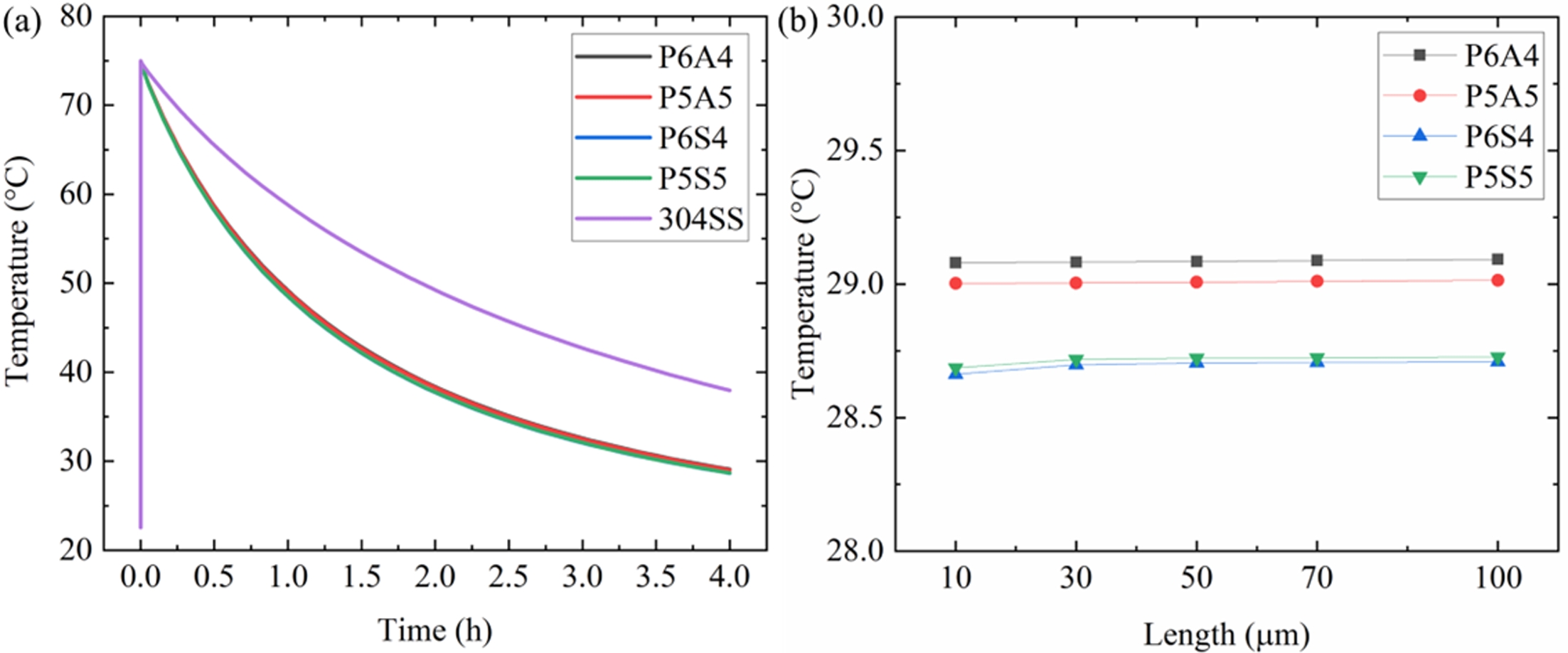

Fig. 2a shows the typical temperature evolution of the outer surface of the 304SS column during cooling, with and without 10 µm-thick ceramic particle–containing coatings. The bare 304SS column reaches 37.9 °C after 4 h of cooling. In contrast, the presence of a coating results in faster cooling. The difference in surface temperature among the columns with various coatings was less than 0.5 °C after 4 h of cooling. P6S4 exhibited the highest cooling rate, followed by P5S5. The surface temperatures of the columns coated with Al2O3 (P6A4 and P5A5) decreased more slowly than those coated with SiC. The cooling curves of P6S4 and P5S5 were almost identical. The final temperatures of P6A4, P5A5, P6S4, and P5S5 were 29.1, 29.0, 28.6, and 28.7 °C, respectively.

The final surface temperatures for various coating thicknesses are shown in Fig. 2b. Each coating exhibited nearly the same temperature regardless of thickness. Because the simulated coating thickness was less than 100 mm heat dissipation was insignificantly affected by the coating thickness. The order of the final temperatures of the coatings matched well with that of the emissivity: the coatings with Al2O3 (~0.920) had lower emissivity than those with SiC (~0.975).

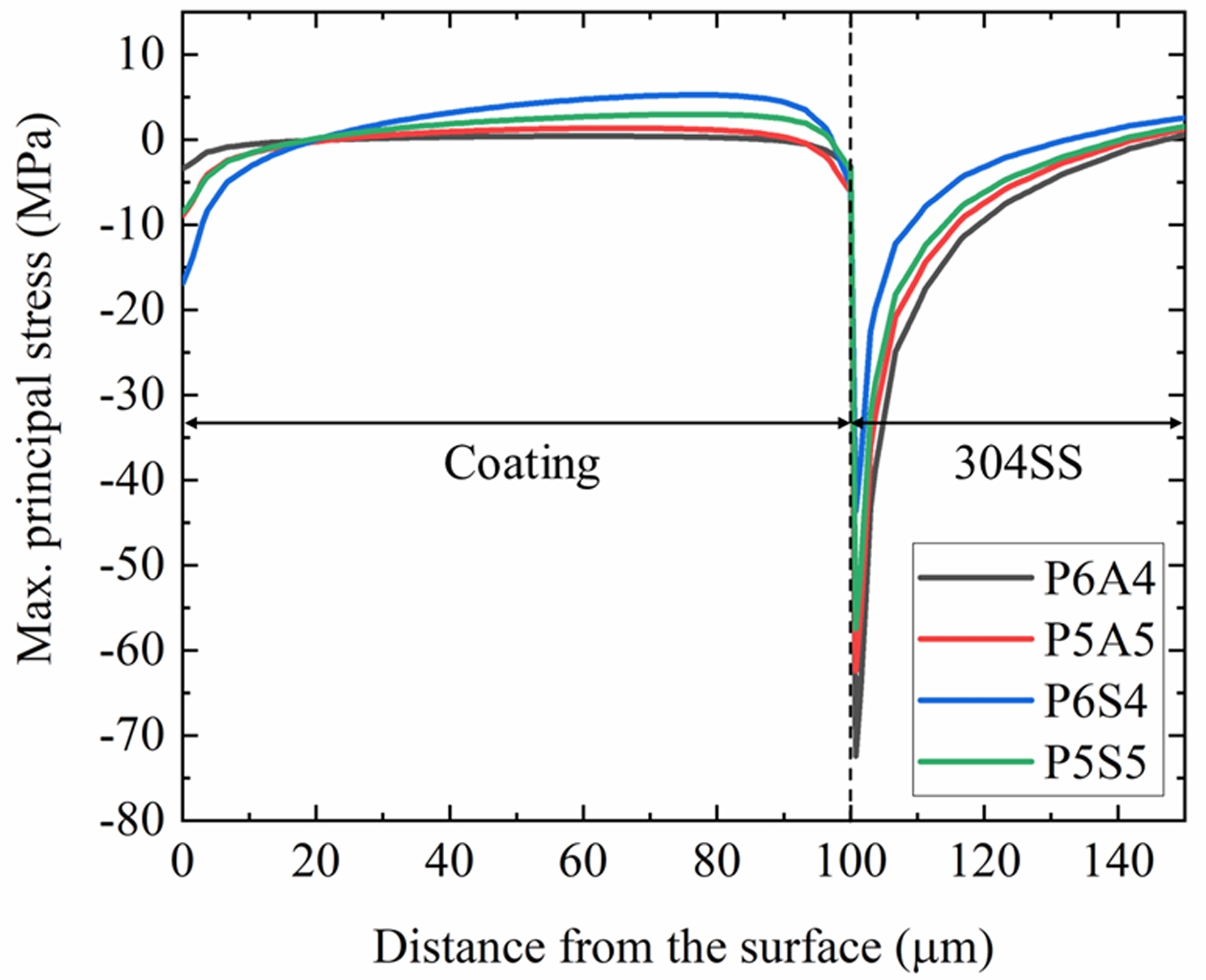

Delamination of the coating occurs at the interface with the substrate during heating and cooling cycles. Therefore, the thermal stress at the interface after one cycle was evaluated. Fig. 3 shows the maximum principal stress profiles along the thickness direction at the bottom of the model (Fig. 2c). The coating thickness was 100 μm.

The stress inside the coatings was relatively uniform, whereas steep stress gradients were observed at the interface between the coating and the 304SS column. P6A4 showed the lowest stress, followed by P5A5, P5S5, and P6S4. The magnitude of the principal stress at the interface is attributed to differences in thermal expansion and elastic properties between 304SS and the coating materials. Since the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) and Young’s modulus of the coatings were smaller than those of 304SS, the coatings experienced large shrinkage during cooling under the constraint of the 304SS substrate.

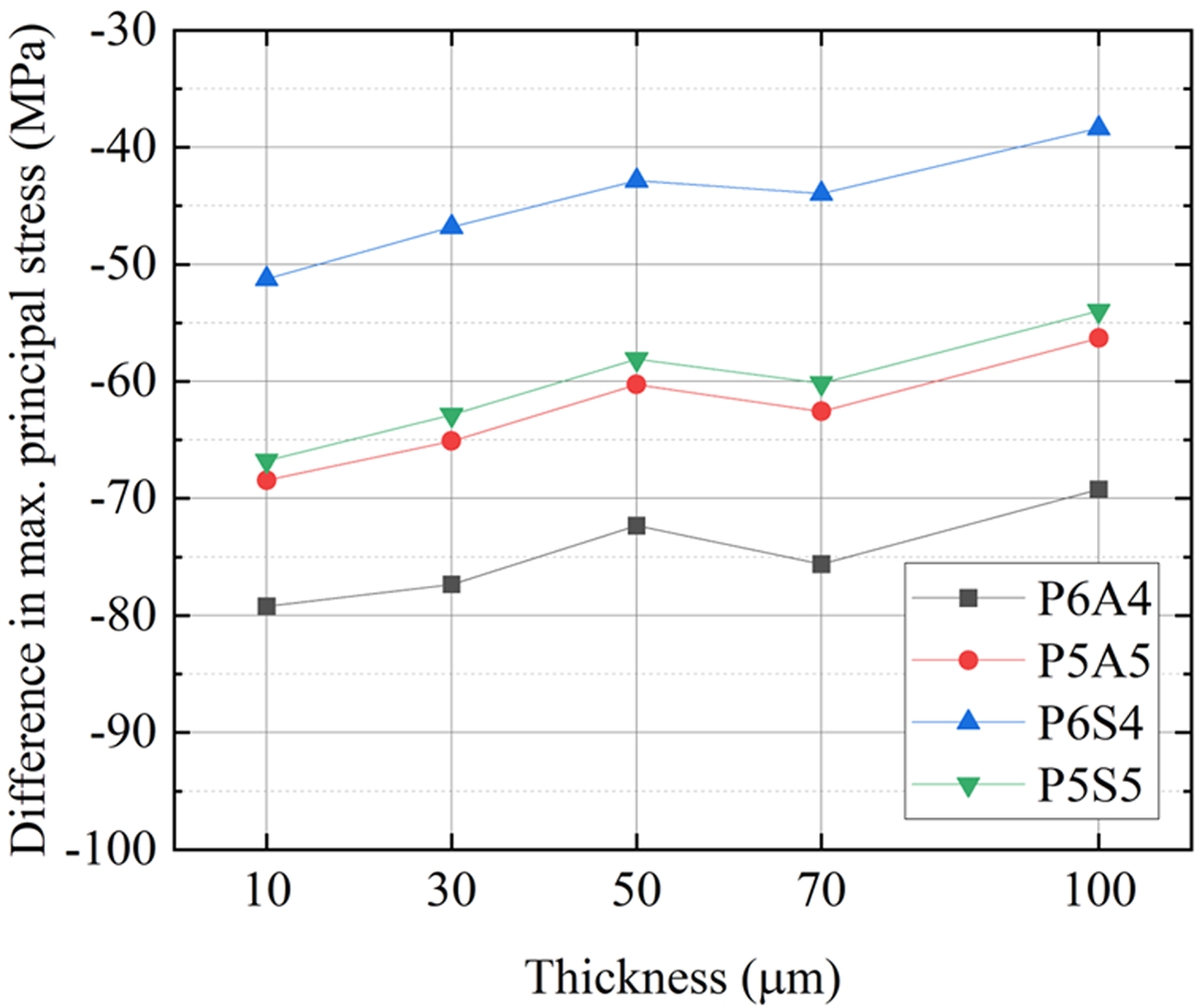

Although the heat dissipation performance of the coatings was independent of the thickness, the evolution of stress at the interface varied with thickness. Fig. 4 presents the difference in maximum principal stress between the coatings and 304SS as a function of thickness. The stress difference decreased with increasing thickness. The SiC-containing polymer coatings experienced lower compressive stress at the interface than the Al2O3-containing coatings at all thickness. These results indicate that thicker coatings are beneficial for minimizing differences in interfacial stress.

The requirements for the coatings are to maximize heat dissipation performance and to minimize the likelihood of coating delamination at the interface. The results from the finite element analysis indicated that P6S4 with a thickness of 100 mm was the most appropriate in this regard. Because the heat dissipation efficiency with any ceramic particle–containing coating was considerably higher than that of bare 304SS, reducing the stress difference at the interface is particularly important. In addition, the principal stresses near the surface of the coated layers are all negative. Since cracking of the coatings occurs when the maximum principal stress exceeds their fracture strength, surface cracking is expected to be negligible for all coatings.

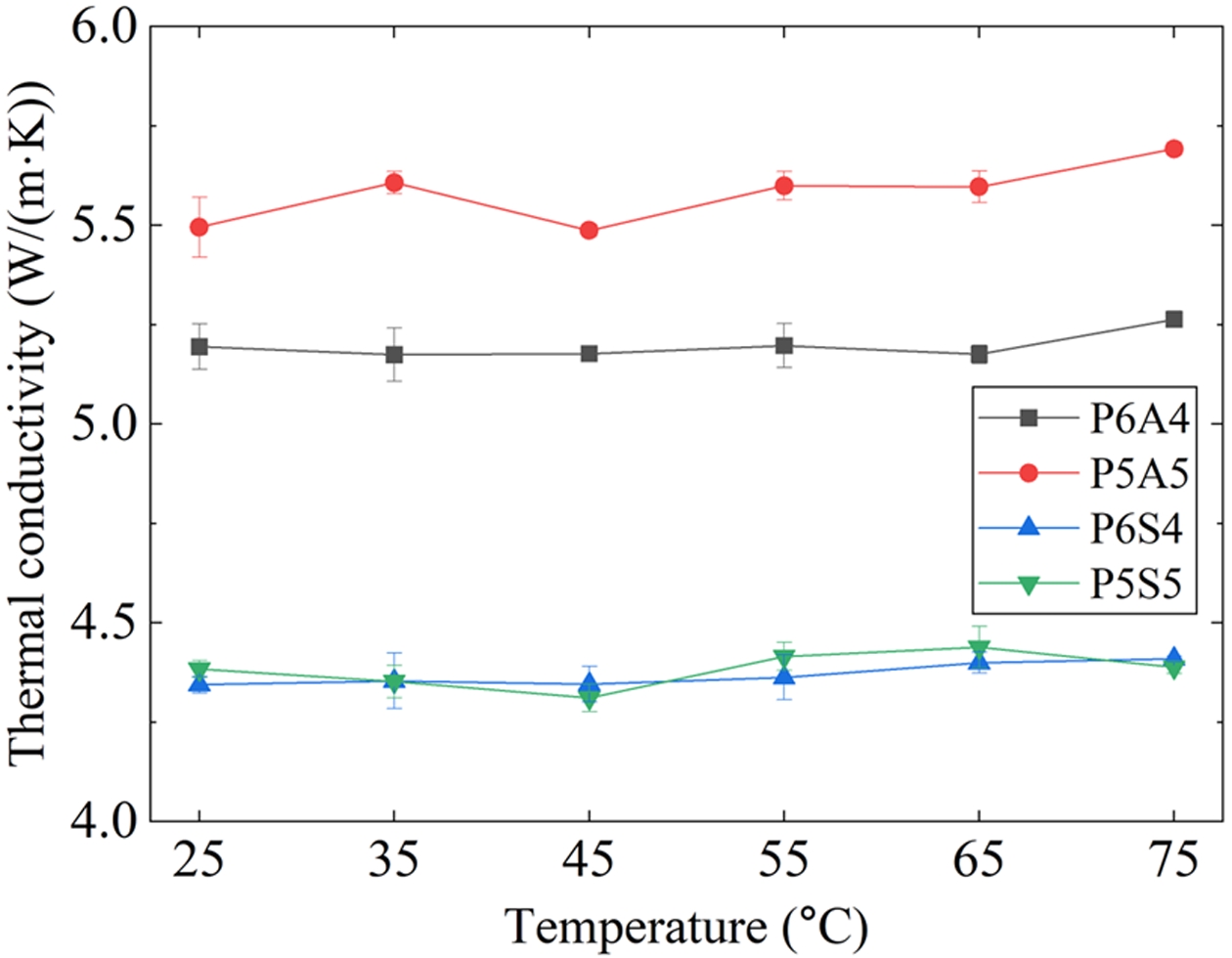

To validate the numerical results, experimental measurements of thermal conductivity were conducted on 304SS plates coated with different ceramic particles, as shown in Fig. 5 as a function of temperature. The thermal conductivities of P6A4 and P6S4 were higher than the estimated values (Table 2), which can be attributed to the presence of the 304SS substrate, whose thermal conductivity is approximately three times higher. For P5A5 and P5S5, the measured thermal conductivities were lower than the predicted values. The lack of continuous conductive pathways due to particle–matrix debonding and coating delamination from the substrate can account for the low thermal conductivity [13]. No significant change in thermal conductivity was observed with increasing temperature.

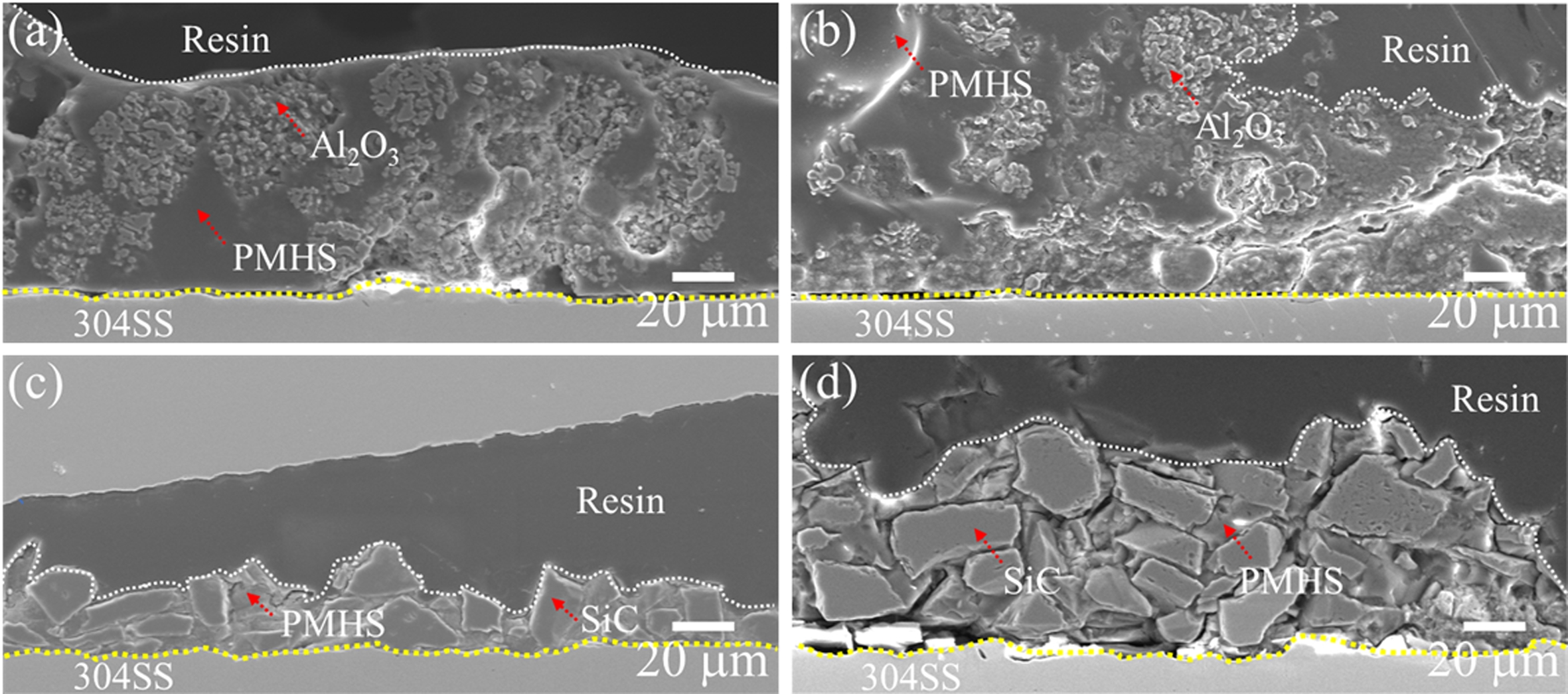

The cross sections of the fabricated samples are shown in Fig. 6. The thicknesses of P6A4, P5A5, P6S4, and P5S5 were 75.5 ± 5.5, 84.6 ± 12.5, 21.2 ± 4.1, and 65.0 ± 8.1, respectively. The thickness increased with particle content. For P6A4 and P5A5, the Al2O3 particles were agglomerated into granules owing to their small particle size, and these granules were connected to each other. The fine connectivity between particles, even in the presence of agglomeration, can be attributed to the high thermal conductivity of the coatings with Al2O3. The gap between the coated layer and substrate was caused by sample preparation. For P6S4, however, no remarkable connection between the SiC particles was observed, and PMHS was present in the gaps between particles. With increasing SiC content (P5S5), pores and cracks were found at the interface between PMHS and the particles. The loss of conductive paths in the coatings with SiC would result in low thermal conductivity, even with increasing particle content.

Under the present choice of ceramic particles and coating process, the most appropriate material for improving heat dissipation is P5A5, which differs from the numerical prediction. Because particle agglomeration and the resulting non-uniform distribution are detrimental to heat dissipation efficiency, future studies will focus on improving particle dispersion and forming continuous conductive paths. In addition, smaller SiC particles are of interest for further investigation, since the numerical results showed that coatings with SiC particles are superior to those with Al2O3 particles.

|

Fig. 2 (a) Temperature changes of the outer coated surface with a thickness of 10 μm over cooling time compared with the bare 304SS and (b) final temperatures of the surface with the various coating thickness. |

|

Fig. 3 Profiles of maximum principal stress at the bottom of the column from the surface of coatings with a thickness of 100 μm to 304SS. |

|

Fig. 4 Difference in maximum principal stress between the coatings and 304SS. |

|

Fig. 5 Thermal conductivity of the 304SS samples coated with ceramic particle-containing polymer coatings. |

|

Fig. 6 SEM cross-sections of 304SS samples coated with (a) P4A6, (b) P5A5, (c) P4S6, and (d) P5S5. |

|

Table 2 Summary of predicted properties of the ceramic particlecontaining polymer coatings. |

In this study, ceramic particle–containing heat dissipation polymer coatings for agricultural applications were numerically designed. Two ceramic particles, Al2O3 and SiC, were considered as additives with a PMHS matrix. The mechanical and thermal properties of PMHS coatings with 40–50 vol%Al2O3 or SiC particles were estimated using microscale RVE models, and the predicted properties were then used to analyze the heat transfer and thermal shock behavior of the coatings in macroscale column models. As the particle content increased, both Young’s modulus and thermal conductivity increased, whereas thermal expansion and specific heat capacity decreased. These changes were more pronounced in coatings with SiC than in those with Al2O3. An increase in heat dissipation efficiency was observed for the coated columns compared to bare 304SS, with coatings containing SiC resulting in slightly lower surface temperatures after cooling than those containing Al2O3. The stress that developed at the interface varied with the type and thickness of the coating. The most suitable material for improving heat dissipation was numerically identified as the coating with 40 vol%SiC (P6S4). The numerical results were experimentally examined by measuring thermal conductivity and observing cross sections. Samples coated with Al2O3/PMHS showed high thermal conductivity (~5.7 W/m·K), whereas lower conductivity (~4.5 W/m·K) was measured for those coated with SiC/PMHS, in contrast to the numerical predictions. The low connectivity between the SiC particles and the presence of defects, including pores and cracks, led to a decrease in thermal conductivity. Based on the measurements, the PMHS coating with 50 vol%Al2O3 particle was selected as the suitable material for improving heat dissipation efficiency. The discrepancy between the numerical and experimental results emphasizes the need for future research on the effects of ceramic particle dispersion and size on heat dissipation efficiency.

This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the Jeollanamdo RISE center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Jeollanamdo, Republic of Korea. (2025-RISE-14-003)

- 1. Al-Mamoori, A., Krishnamurthy, A., Rownaghi, A.A., and Rezaei, F., “Carbon Capture and Utilization Update,” Energy Technology, Vol. 5, No. 6, 2017, pp. 834-849.

-

- 2. Ghiat, I., Mahmood, F., Govindan, R., and Al-Ansari, T., “CO₂ Utilisation in Agricultural Greenhouses: A Novel Plant to Plant Approach Driven by Bioenergy with Carbon Capture Systems within the Energy, Water and Food Nexus,” Energy Conversion and Management, Vol. 228, 2021, pp. 113668.

-

- 3. Gao, W., Liang, S., Wang, R., Jiang, Q., Zhang, Y., Zheng, Q., Xie, B., Toe, C.Y., Zhu, X., Wang, J., Huang, L., Gao, Y., Wang, Z., Jo, C., Wang, Q., Wang, L., Liu, Y., Louis, B., Scott, J., Roger, A.-C., Amal, R., He, H., and Park, S.-E., “Industrial Carbon Dioxide Capture and Utilization: State of the Art and Future Challenges,” Chemical Society Reviews, Vol. 49, No. 23, 2020, pp. 8584-8686.

-

- 4. Siegelman, R.L., Kim, E.J., and Long, J.R., “Porous Materials for Carbon Dioxide Separations,” Nature Materials, Vol. 20, No. 8, 2021, pp. 1060-1072.

-

- 5. Chen, H., Ginzburg, V.V., Yang, J., Yang, Y., Liu, W., Huang, Y., Du, L., and Chen, B., “Thermal Conductivity of Polymer-Based Composites: Fundamentals and Applications,” Progress in Polymer Science, Vol. 59, 2016, pp. 41-85.

-

- 6. Liu, R., Wang, S., Zhou, Z., Zhang, K., Wang, G., Chen, C., and Long, Y., “Materials in Radiative Cooling Technologies,” Advanced Materials, Vol. 37, No. 2, 2025, pp. 2401577.

-

- 7. Min, S.-B., and Kim, C.B., “Manipulating Anisotropic Filler Structure in Polymer Composite for Heat Dissipating Materials: A Mini Review,” Composites Research, Vol. 35, No. 6, 2022, pp. 431-438.

-

- 8. Yoon, S., Seo, J., Jung, J., Choi, M., Lee, B.J., and Kim, J.B., “Improving Radiative Cooling Performance via Strong Solar Reflection by Dense Al2O3 Particles in a Polymeric Film,” International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, Vol. 227, 2024, pp. 125574.

-

- 9. Pan, Z., Liu, Y., Wang, F., Lu, G., Yang, F., and Cheng, F., “Al2O3 Dispersion-Induced Micropapillae in an Epoxy Composite Coating and Implications in Thermal Conductivity,” ACS Omega, Vol. 6, No. 28, 2021, pp. 17870-17879.

-

- 10. Bao, H., Yan, C., Wang, B., Fang, X., Zhao, C.Y., and Ruan, X., “Double-Layer Nanoparticle-Based Coatings for Efficient Terrestrial Radiative Cooling,” Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, Vol. 168, 2017, pp. 78-84.

-

- 11. Jung, J., Yoon, S., Kim, B., and Kim, J.B., “Development of High-Performance Flexible Radiative Cooling Film Using PDMS/TiO2 Microparticles,” Micromachines, Vol. 14, No. 12, 2023, 2223.

-

- 12. Atiganyanun, S., Plumley, J.B., Han, S.J., Hsu, K., Cytrynbaum, J., Peng, T.L., Han, S.M., and Han, S.E., “Effective Radiative Cooling by Paint-Format Microsphere-Based Photonic Random Media,” ACS Photonics, Vol. 5, No. 4, 2018, pp. 1181-1187.

-

- 13. Han, Z., and Fina, A., “Thermal Conductivity of Carbon Nanotubes and Their Polymer Nanocomposites: A Review,” Progress in Polymer Science, Vol. 36, No. 7, 2011, pp. 914-944.

-

- 14. Suryawanshi, C.N., and Lin, C.-T., “Radiative Cooling: Lattice Quantization and Surface Emissivity in Thin Coatings,” ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, Vol. 1, No. 6, 2009, pp. 1334-1338.

-

- 15. Zou, Y., Wang, Y., Wei, D., Ge, Y., Ouyang, J., Jia, D., and Zhou, Y., “Facile One-Step Fabrication of Multilayer Nanocomposite Coating for Radiative Heat Dissipation,” ACS Applied Electronic Materials, Vol. 1, No. 8, 2019, pp. 1527-1537.

-

- 16. Wang, T., Jiang, Y., Huang, J., and Wang, S., “High Thermal Conductive Paraffin/Calcium Carbonate Phase Change Microcapsules Based Composites with Different Carbon Network,” Applied Energy, Vol. 218, 2018, pp. 184-191.

-

- 17. He, X., Li, Y., Wang, L., Sun, Y., and Zhang, S., “High Emissivity Coatings for High Temperature Application: Progress and Prospect,” Thin Solid Films, Vol. 517, No. 17, 2009, pp. 5120-5129.

-

- 18. Zhang, H., and Fan, D., “Improving Heat Dissipation and Temperature Uniformity in Radiative Cooling Coating,” Energy Technology, Vol. 8, No. 5, 2020, pp. 1901362.

-

- 19. Cho, Y.J., Lee, W., and Park, H.Y., “Finite Element Modeling of Tensile Deformation Behaviors of Iron Syntactic Foam with Hollow Glass Microspheres,” Materials, Vol. 10, No. 10, 2017, pp. 1201-1215.

-

- 20. Jang, J.H., and Cho, Y.J., “Effects of Interfacial Debonding of Microspheres on Mechanical Properties of Iron Matrix Syntactic Foams: Roles of Ni Coating,” Mechanics of Advanced Materials and Structures, Vol. 32, 2025, pp. 1-14.

-

- 21. Zhang, X., Qiu, J., Zhao, J., Li, X., and Liu, L., “Complex Refractive Indices Measurements of Polymers in Infrared Bands,” Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer, Vol. 252, 2020, pp. 107063.

-

- 22. Franta, D., Nečas, D., Ohlídal, I., and Giglia, A., “Dispersion Model for Optical Thin Films Applicable in Wide Spectral Range,” Optical Systems Design 2015:Optical Fabrication, Testing, and Metrology V, Vol. 9628, 2015, pp. 342-353.

-

- 23. Larruquert, J.I., Pérez-Marín, A.P., García-Cortés, S., Rodríguez-de Marcos, L., Aznárez, J.A., and Méndez, J.A., “Self-Consistent Optical Constants of SiC Thin Films,” Journal of the Optical Society of America A, Vol. 28, No. 11, 2011, pp. 2340-2345.

-

- 24. Liu, X., Tian, Y., Chen, F., hanekar, A., Antezza, M., and Zheng, Y., “Continuously Variable Emission for Mechanical Deformation Induced Radiative Cooling,” Communications Materials, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2020, pp. 95.

-

- 25. Ordóñez, F., Caliot, C., Bataille, F., and Lauriat, G., “Optimization of the Optical Particle Properties for a High Temperature Solar Particle Receiver,” Solar Energy, Vol. 99, 2014, pp. 299-311.

-

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 38(6): 696-702

Published on Dec 31, 2025

- 10.7234/composres.2025.38.6.696

- Received on Nov 26, 2025

- Revised on Dec 19, 2025

- Accepted on Dec 22, 2025

Services

Services

- Abstract

1. introduction

2. experimental procedures

3. results and discussion

4. conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- References

- Full Text PDF

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Yi Je Cho

-

Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Sunchon National University, Suncheon 57922, Korea

- E-mail: yijecho@scnu.ac.kr

Copyright ⓒ The Korean Society for Composite Materials. All rights reserved.

Copyright ⓒ The Korean Society for Composite Materials. All rights reserved.